On Monday I wrote a bit about the history of the Zippe-type gas centrifuge. What’s fascinating about the Zippe centrifuges, for me, is that they were pushed internationally for the purpose of commercialization, and because of their origin outside of the United States (and their post-Atoms for Peace publicity), they were not put under as heavy restrictions as other uranium enrichment technologies — despite the fact that they are really the ideal enrichment method for a potential new proliferator. This created a major problem for the United States. Centrifuge technology was both hard for the US to meaningfully control (since it didn’t originate in secret American labs), and US companies were eager to “stay competitive” with Europe in the vast new frontier of enrichment possibilities they opened up (which seemed like big money in the 1960s, when the future of nuclear power was still rosy). For this week’s document(s), I want to share two different (short) positions on what we might call the “centrifuge problem” of the 1960s.

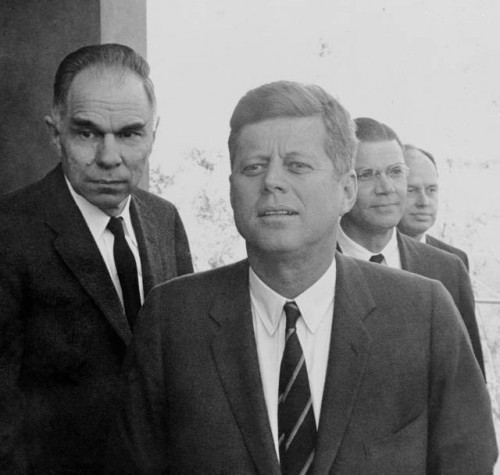

Glenn Seaborg (left) and Robert McNamara (right) flank President Kennedy as he visits the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in 1962

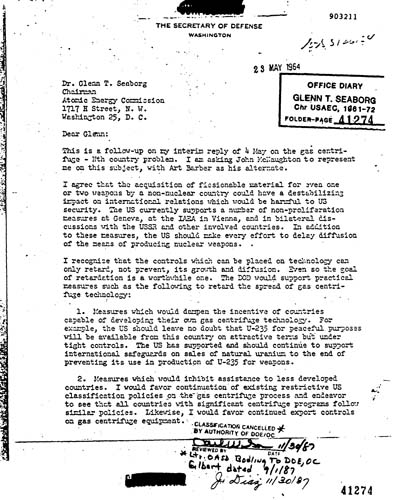

The first is a 1964 memo from Robert S. McNamara, then the Secretary of Defense, to Glenn T. Seaborg, then the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission. It comes at a time — about six months prior to the first Chinese nuclear test — where the United States started to get really serious about proliferation, or as it was often called then, the “Nth country problem.”1

McNamara’s memo aimed to confront the problem of centrifuge proliferation head-on. Proliferation was a problem in McNamara’s eyes because, “...the acquisition of fissionable material for even one or two weapons by a non-nuclear country could have a destabilizing impact on international relations which would be harmful to US security.” (This is, of course, exactly why helping other countries proliferate might seem like a good idea to some countries, as Matthew Kroenig has argued in his fairly recent book, Exporting the Bomb.)

But McNamara knew he couldn’t end proliferation through simple technical means: “I recognize that the controls which can be placed on technology can only retard, not prevent, its growth and diffusion. Even so the goal of retardation is a worthwhile one.” This is actually a very old argument related to the benefits of secrecy: it doesn’t stop diffusion of information, but it does slow it down. And slowing it down can be strategically valuable.

Supporting this “retardation” goal (a somewhat unfortunate choice of words), McNamara wanted to slow down the diffusion of centrifuge information. His methods:

- “…dampen the incentive of countries capable of developing their own gas centrifuge technology.” That is, guarantee nuclear fuel to countries so they are dependent on the US for enrichment and don’t feel they need to develop their own enrichment capabilities. He also thinks that the US should support safeguards on natural uranium — which is interesting since as far as I know, unenriched, natural uranium is not safeguarded today.

- “…inhibit assistance to less developed countries.” Specifically he means keeping classification and export controls up in the US program, since that will make nuclear newbies have a harder time.

- “…support US gas centrifuge technology at a high level so that the US can stay abreast, or ahead, of developments in other countries.” This is a very good task to send to the Chairman of the AEC: full steam ahead with centrifuge development! But keep it secret. McNamara is no doubt aware that half of the problem here is that the US hadn’t kept abreast, or ahead, of centrifuge developments in other countries (see my previous post on this).

Lastly, Seaborg had asked McNamara if there were any US security objectives that non-proliferation policy might interfere with. (An interesting question.) McNamara says no — the only issue hinted at is the basing of nuclear weapons in NATO countries (“nuclear sharing”), but McNamara seems pretty confident that he doesn’t consider that to be proliferation since it is not a creation of an “independent” nuclear state. (This was a major sticking point for the NPT negotiations in the late 1960s; the USSR was desperately afraid of giving the West German “revanchists” control of nuclear weapons and tried to use the NPT as a way of opposing nuclear sharing policies.)

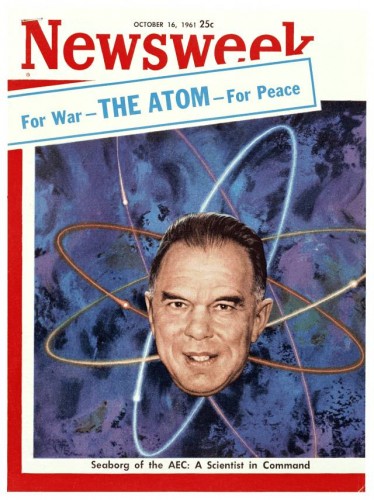

Now let’s go to the other document, an extract from Seaborg’s office diary from 1968. Seaborg’s office diary entries are generally speaking quite short and not usually very revealing, but this one is interesting. It concerns his day on Monday, November 11, 1968. Here’s the first relevant section:2

At 10 a.m. I presided over [Atomic Energy] Commission Meeting 2352 (action summary attached) [not attached]. At the Commission Meeting we discussed the possibility of modifying our policy of secrecy on our gaseous diffusion and gas centrifuge methods for enriching U-235. The Europeans and Japanese are developing these methods and our policy seems to be outmoded if we want to influence them and stay abreast of them. Despite objections from [Commissioner James T.] Ramey, who prefers the status quo, we asked the staff to make a study, with the aim of coming up with various plans to make it possible to cooperate with the Europeans and Japanese in this area.

So this is an interesting counter to the McNamara concern. The Europeans and Japanese were pushing ahead in both centrifuge and diffusion technology, and there was a question as to whether the AEC should loosen their restrictions in order to “influence them and stay abreast of them.” At least one AEC Commissioner wanted to take a conservative approach, but Seaborg and the others were interested enough in the possibility to order up a staff study, which was often the first step towards a policy change.

There is one more relevant part of that day’s diary entry; that evening, Seaborg went to see the German delegation to a nuclear industry conference. Here’s what he wrote:

Dr. Michael Higatsberger (of Austria) told me the AEC briefings at Oak Ridge last Thursday and Friday on our nuclear fuel policy were very successful and may have convinced many Europeans that they shouldn’t build an enriching facility soon. Charles Robbins (AIF) told me about industry feeling that AEC suppression of industrial work on gas centrifuge is counter to American method of doing business.

Another interesting paring — an Austrian saying that the US had probably convinced the Europeans not to create in their own collective enrichment facility, and an American nuclear industry representative (the AIF was the Atomic Industrial Forum, a nuclear lobby group) saying that AEC control over centrifuge work is “counter to [the] American method of doing business.” (The UK, Netherlands, and Germany did create URENCO in 1971, so not all of them were apparently convinced. URENCO uses gas centrifuges for its enrichment, and is where A.Q. Khan got access to the centrifuge technology that he later took back to Pakistan and exported to quite a few other places.)

What I like about these two documents is they paint a picture of the various political, technical, and economic forces pulling in different directions on the centrifuge problem. Gas centrifuges, like all enrichment technology, have been duel-use since birth, but the fact that they developed outside of US auspices made them especially difficult to control. This difficulty then presented the problem of whether one ought to try and control them, and if so, how. Heavy controls might slow things down, but it also could easily encourage others to press ahead with independent development. Loosening restrictions might increase diffusion, but could also increase dependence on US assistance.

- Citation: Robert S. McNamara to Glenn T. Seaborg (23 May 1964), copy in Nuclear Testing Archive, Las Vegas, NV, document NV0903211. [↩]

- Glenn T. Seaborg, Office Diary entry (11 November 1968), copy in Nuclear Testing Archive, Las Vegas, NV, document NV0910540. [↩]

“which is interesting since as far as I know, unenriched, natural uranium is not safeguarded today”

It is, at least in the European Union: “the ‘categories’ (of nuclear material) are natural uranium, depleted

uranium, uranium enriched in uranium-235 or uranium-233, thorium, plutonium, and any other material which the Council may determine, acting by a qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission;” (as an engineer-physicist, I just love the last part of the definition). In the EU, the current legal framework for the application of safeguards under the EURATOM Treaty is Regulation 302/05.

I am not sure about the IAEA regulations, with google I found this table, it does not list unirradiated natural or depleted U as nuclear material.

[…] round off this week of centrifuges, I thought we might actually look at a few of them. Photographs of real-life enrichment […]