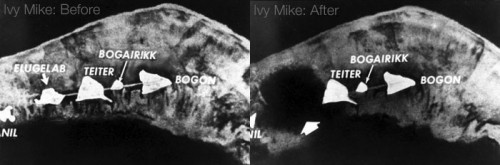

On November 1, 1952, the United States detonated the world’s first hydrogen bomb.1 Shot MIKE of Operation Ivy was the culmination of nearly a decade of work on developing thermonuclear weapons, and it released an explosive force equivalent to 10.4 million tons of TNT — some 800 times the explosive force of Hiroshima, capable of setting fire to an area of over a thousand square miles.

The world had entered the megaton age, but the United States didn’t want anybody to know about it.

Which is an odd thing, if you think about it. It’s true, the first atomic bomb test — “Trinity” — had been kept a secret at the time. But only because the U.S. planned to use it on Japan quickly and wanted it to be a surprise. There was no “operational” reason for keeping the MIKE test a secret, except for the fact that, well, it wasn’t actually really ready for prime-time, as far as weapons went. MIKE was a big, clunky cryogenic test apparatus that weighed over 50 tons. It had been designed (by Dick Garwin) to prove a point, not to fit on an airplane. They did manage to scale it down a bit as five “Emergency Capability” weapons (the “Jughead” bombs), but these required specialized plane modifications to field (and only one plane was so modified), and even then, one wonders how reliable they were considered. (And even these weren’t produced until 1954, shortly before the U.S. developed more easily weaponized solid-fuel hydrogen bombs.)

Still, one might ask again why the U.S. tried to keep it secret, and from whom. The thing is, keeping it secret from the USSR just wasn’t an option: when you set off 10 megatons in the Pacific Ocean, people are going to notice. Now, it’s true that the Soviets later claimed that they botched their fallout monitoring program at that stage of things (and thus apparently were unable to analyze the MIKE fallout to the degree that would have revealed fundamental design information, thus saving Soviet dignity when they came up with the same idea independently!),2 but it’s clear that they were aware that something big had happened in the Pacific Ocean. And the only thing that big would have been an H-bomb.

The secrecy of the H-bomb has long been an interest of mine, because it was instituted so early (Truman put the AEC under a “gag” on discussing H-bomb topics in 1950, which they struggled to get reversed), and persisted for a relatively long time (the US didn’t officially admit to having H-bombs until 1954, after the Castle BRAVO accident) despite the weighty subject matter. Information on the Ivy Mike shot wasn’t released until nearly two years after it was detonated, which is a long time to try and keep something that big secret!

Who were they trying to keep it from? Well, everybody. The timing and circumstances of MIKE were not politically ideal. It was detonated just days before the 1952 Presidential election, and there was considerable question to whether it should be delayed until after the election took place. In the end it was decided that delaying it would be a politically tricky thing, so they just went ahead with it when they were ready. Truman didn’t make it a political issue, though he easily could have. When President-elect Eisenhower was briefed on it, he was relieved that the AEC hadn’t told anybody, because he didn’t want to tip off the Russians to anything whatsoever.3 All that was immediately let out was a terse statement that admitted that the test series “the test program included experiments contributing to thermonuclear weapons research” — the same thing they had said after Operation Greenhouse. From that point until the Operation Castle debacle it just never seemed like the right time to say anything.

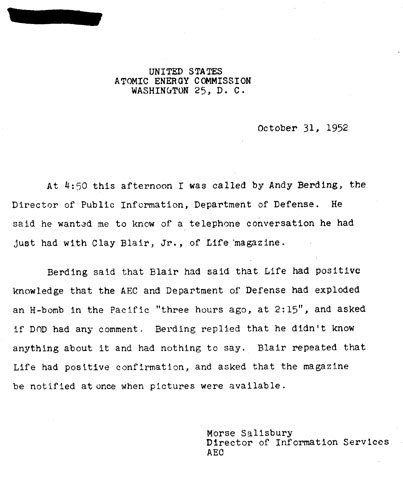

Of course, as I said, you can’t really keep something that large truly secret. And indeed — Ivy MIKE leaked almost immediately. Thus we turn to this week’s document, a series of AEC correspondence by Morris Salisbury, their public relations officer, Gordon Dean, the Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, and J. Edgar Hoover, infamous head of the FBI.4

Only a few hours after the first H-bomb detonation, the AEC public relations man got a call from someone at the Department of Defense who had got off the phone with Clay Blair, Jr., at Life magazine wanting to confirm that the US had indeed just detonated a hydrogen bomb. Just prior to that, they had gotten another phone call from Time magazine:

Hobbing [Time]: Is this the big day?

Thompson [AEC]: Why don’t you tell me? What are you talking about?

Hobbing: We understand that the H-bomb has just been set off.

Thompson: We have a standard policy of no comment about weapons tests. We haven’t anything to say in that field.

Hobbing: Aren’t you getting out a release, don’t you usually issue releases after you have made a shot?

Thompson: We have at times issued releases or statements after a shot in Nevada. We have never followed such procedure on tests at Eniwetok.

Hobbing: Don’t you have any releases coming out there this afternoon?

Thompson: I don’t know offhand. I’ll have to check.

Hobbing: I mean about H-bombs.

Thompson: No.

A not entirely compelling performance on behalf of the AEC representative, there. Dean opted to have the FBI try and track down the source of the leak — the exact place and time of the shot was considered extremely sensitive information (because it would help the Soviets reconstruct information from the fallout), and the fact that it involved an H-bomb at all meant that it was “restricted data” (the unauthorized dissemination of which could even carry the death penalty).

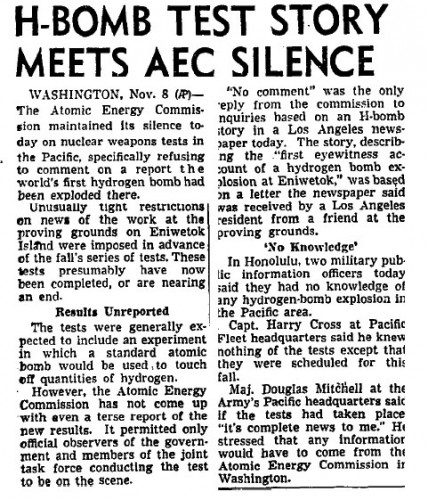

Over the course of the week the story made its way into the press — and the AEC’s secrecy on the issue itself became a main part of the story.

“The United States may be keeping secret an explosion of the world’s first full-scale hydrogen bomb.” (L.A. Times, November 7, 1952)

” ‘No Comment’ was the only reply from the commission to inquiries based on an H-bomb story story in a Los Angeles newspaper today.” (L.A. Times, November 9, 1952)

Finally the AEC release the terse statement I mentioned earlier, which, when paired with the rumors, and several “first-hand accounts” made the H-bomb test a fairly “open secret.”

It’s still worth wondering, why try to keep it so secret? I mean, as we’ve seen from the film (released later), Operation Ivy was no small affair. (Interestingly, and this was news to me, an Air Force pilot actually died while taking fallout samples. Not from the radiation, mind you, but because he ran out of fuel and crashed the plane.5 This is the only acute, immediate death I’ve ever heard of during a U.S. nuclear test. Are there more?) Over 2,500 people were present at the test site, and the bomb itself was pretty conspicuous. As far as I know, nobody was ever charged with “leaking” the news about the MIKE shot.

A short version is to say that by this point, the AEC was taking all of its guidance on public releases relating to the H-bomb from the National Security Council, who saw no benefit to transparency. There’s more to this story, but we’ll leave it at that for now.

A few parting observations:

- In all of the news coverage, notice that it is the AEC who gets the blame for the secrecy. This isn’t exactly true — the “no comment on the H-bomb” policy had been decided before the shot by the National Security Council, and the post-shot silence was dictated by both Truman and Eisenhower. But the very secrecy of the matter obscures the source of the secrecy.

- In a sense, one could see the U.S. as participating in a form of “strategic opacity” regarding its possession or non-possession of a hydrogen bomb between 1952 and 1954. Like Israel today, the U.S. then derived some advantage from its vagueness — if everyone “knew” that the U.S. had an H-bomb, but the U.S. didn’t announce it, it could help avoid troublesome international issues (like criticism from allied countries who decried the H-bomb effort) while also avoiding several acute strategic weaknesses (like the fact that their “H-bomb” was not yet really a deliverable military weapon).

- On the other hand, the H-bomb issue as a whole was one of the real turning points with respects to the AEC and the press. It was in the 1950s that the AEC’s relationship with the press soured in a bad way, and when it got its most fearsome reputation as an agent of censorship and an enemy of disclosure. Some of this was deserved, but some of this was not. As pointed out, a lot of that secrecy didn’t derive from the AEC at all, but other sources of power it was beholden to.

Ultimately, like so much regarding the hydrogen bomb (more on this in a future post), one has to wonder what it all added up to. The AEC was already in a pretty prime strategic relationship with regards to the arms race, and it didn’t have any great reason to assume otherwise. I don’t think it got them very much to be secretive, but I do think it hurt them. Then again, it wasn’t entirely up to them what was secret and what wasn’t — a case of “gambling with other people’s money,” or, more correctly, “gambling with other agency’s reputations,” on behalf of the NSC.

- Note that it was November 1 local, Eniwetok time — in the U.S. itself it was Halloween, which I find appropriate. [↩]

- See Hugh Gusterson, “Death of the authors of death: Prestige and creativity among nuclear weapons scientists,” in Mario Biagioli and Peter Galison, eds., Scientific authorship: Credit and intellectual property in science (New York: Routledge, 2003), 281-307, riffing off of the account in David Holloway’s Stalin and the Bomb. [↩]

- Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl, Atoms for Peace and War, 1953-1961 (Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, 1989), 3-4. [↩]

- Roy B. Snapp, “Note by the Secretary – Letter to J. Edgar Hoover, Operation Ivy, AEC 483/33,” (18 November 1952), copy in Nuclear Testing Archive, Las Vegas, NV, as document NV0409009. [↩]

- Mark Wolverton, “Into the Mushroom Cloud,” Air & Space (August 2009). [↩]

Google satellite maps have some curious resolution problems in that area. Elugelab area seems to be at standard good resolution, then there is a stripe of poorer resolution (Teiter through ~1/2 of Bogon, then back to good resolution. Why would someone care about a sat-image of a deceased island?

Could it be that they don’t care enough? My understanding is that the very high-resolution Google Maps/Earth imagery is taken by planes, not satellites, so an isolated slice out there might come from just not having enough cameras over the area. The low-res stuff is credited to NASA (in Google Earth), the high-res stuff to DigitalGlobe, which doesn’t clarify much other than it being two separate data sets (and not, say, one intentionally-blurred dataset). Bing Maps has it in high-resolution, in any case.

Not caring enough it’s likely, but bit differently. The high-resolution satellites usually take photos on places and times that someone is willing to pay. The satellites need to pass within certain distance and during daylight hours to take pictures and almost every area where pictures needs some orbit corrections to hit close enough. And that in turn burns the limited stock of fuel the satellites have. Because of this, the companies really take pictures of areas where someone pays for the pictures to be taken. And something as prosaic as clouds in a certain area during the picture-taking process will block the vision of the satellite. It might be that the poorer area of resolution was just occluded by clouds when the satellite was passing. In the more populated areas someone would be needing new photos sooner or later, so there the areas blocked by clouds during the first pass will be photographed usually pretty quickly. But there likely isn’t many parties needing satellite photos over the Pacific Islands, so if they got what they needed from that pass, it might take a while for anyone to buy another pass of the area or for one of the satellites passing by chance of the area when they have “free time”.

One interesting point about the satellite photos is that at leas some years ago the companies had two alternative pricing schedules. The basic one that most people use gives you the photos of the area, but they are also buyable by anyone else and provided to Google Earth and similar services. The (considerably) more expensive one gives total exclusive rights of the photos to buyer.

Two possible reasons for the secrecy:

1) A reflexive “everything to do with the bomb is secret” mentality. All essential data on weapons is “born classified,” and the Mike test certainly would have been classified – design data, timing, place, etc. No reason to change that just because the test took place, at least in the minds of the classifiers. Political motivations could have been different, although they may well have tilted toward Israeli-like opacity at that time. After all, there was a difference of opinion within the United States as to the desirability of these weapons.

2) Something of a subset of the above, but different enough to be called out, the idea that letting people know that such a thing was possible was half or more of the secret. This was certainly operative for the atomic bomb in the forties, and the idea may have persisted into the early fifties. Figuring out how to do this was no picnic, as Ed Teller might have admitted in a weak moment.

Hi Cheryl,

A great comment.

I agree with your first point to a degree but I’d qualify it by noting that before 1950, the idea that you would try to keep something as big as the H-bomb a total secret would have been dismissed as pretty impossible if not unproductive. Which is to say, I do think that by that point they were in a mode of reflexive secrecy (especially about the H-bomb), but I wouldn’t over-state its universality.

(I have a paper on this in the works, though when it will get done, much less out the door, is an open question. 1950 was a big turning point in how the AEC handled secrecy for a number of reasons relating specifically to the H-bomb. Their stance on Ivy, I would argue, is quite different than their stance on prior test series, and their complete tight-lippedness over it, in the face of leaks and speculation, is very much a by-product of the H-bomb debate. This is not to overstate the transparency of the AEC prior to 1950, of course.)

Your second point is also a very good one, as well. Knowing the H-bomb could be done (and done with the bomb technology of 1950) narrowed down the possibilities quite a bit. The post I am planning for Monday will get into this a bit.

For an interesting interview with Dick Garwin about his work on this project and thoughts about other contemporary nuclear issues, copy and past this in your web browser: http://daisyalliance.org/radio-programs/people-who-make-difference-in-arms-control/Richard-Garwin-7.21.09-BR.m3u

[…] through diligent research into primary sources. Here’s a great example: an exploration of secrecy and leaks in the IVY MIKE H-bomb test. This discussion is, of course, applicable to the recent flapping about the (probably unlawful and […]

[…] announce they had the bomb — he saw no reason in giving anything away. (A book that the US would start taking pages from around the same […]

Alex,

I think you’re right about the “timing”being a significant aspect of hwy it was kept secret, but with a bit of a twist. I agree that there was an aspect of nuclear opacity involved, too.

It is true that knowing the exact timing of the shot could have been helpful to the Russians in analyzing fallout samples. However, in the absence of exact timing info this information can be directly inferred from the sample itself. There will be a range of “birthdates” for isotopes in a sample from a reactor accident, for instance, while fallout from a nuclear explosion will produce a group of differing isotopes that have the same birthdate — at the time of the criticality of the device. In fact, this feature of fallout was used to rather accurately backtrack the timing and location of the first Soviet test in late August 1949. It was only later that acoustic signals were found to correlate with the calculated shot time of the various samples, which helped confirm things nicely. Having an exact shot time is helpful, but not absolutely necessary.

So why was denying the Russians knowledge of the exact shot time still critical? I suspect that the first experiments with EMP detection were underway, although I don’t recall being able to firmly establish that this was the case as early as IVY MIKE. I do know that AFOAT-1 had their global EMP network operational by 1958, with development underway by 1955, which suggests that R&D work on a phenomena with potential long range detection benefits somewhat earlier than that.

It may have been IVY MIKE that brought attention to the issue of EMP. I have a short written memoir by one of the wingmen of the sampler pilot killed when his plane ran out of fuel. He remarked in it on the radio blackout that followed the shot interfering with their work IIRC, there were some other such early references to EMP.

The great thing about EMP was that, unlike fallout, seismic and acoustic techniques, it provided instantaneous notification of a nuclear explosion. Thus, it provided a means to alerting monitors to examine other sources for incoming signals that arrive via various delayed paths. But this feature of EMP also provide a resource for warfighting, effectively going beyond AFOAT-1’s original intelligence mission. EMP signals were looked at as possibly providing early warning of attacks by providing extended attack warning time. There was some effort put into this use of EMP, but the development of BMEWS and satellite based bhangmeters largely superseded the use of EMP in the early warning role.

But EMP was hardly on the ashbin of history yet. I’m still putting the pieces together, but it appears that the U2 played a role in EMP detection also. Some of SAC’s 4080th SRW U2s, which were heavily involved in high altitude sampling, flew with what was called “sferics” equipment. At first I thought that this was simply some sort of electronic warfare gear. However, I’m fairly certain now that “sferics” was actually a cover name for EMP detection gear. This would provide the U2 with a wartime mission to detect and locate nuclear explosions, on Russian territory to provide SAC with battle damage assessment and to prevent attacks on domestic and overseas bases for civil and active defense purposes.

So there were a number of reasons for keeping IVY MIKE secret that had to do with denying the Russians the opportunity to use US shots as tests for Soviet detection networks, as well as to develop American countermeasures and detection networks. But it’s true that you can’t hide a light like that under a basket, no matter how much secrecy.

I worded the concluding sentence of the next to the last paragraph. I mean to say:

This would provide the U2 with a wartime mission to detect and locate nuclear explosions, on Russian territory to provide SAC with battle damage assessment and to _assess_ attacks on domestic and overseas bases for civil and active defense purposes.

[…] come out pretty well on top of things even if the Soviets had roared ahead with their own program. Last Wednesday, I talked about how the test of the first H-bomb in November 1952, Ivy MIKE, leaked out almost […]

This would really be a bomb if the general public knows this (pun intended). Another great reminder that the government can suppress information from the public if they so wanted.

Well, they can try. They’re not guaranteed success.

This post has been very useful for my chapter about media discourse and the H-bomb. Thank you.

As for whether anyone else had been killed by a nuclear test, one worker at the NTS died at the Fusileer Midas Myth/Milagro test on Rainier Mesa in February of 1983. He and his team went to the test’s trailer park on top of the mesa a short time after the test, and was trapped in a delayed subsidence, which weren’t supposed to happen on the mesa. The other 14 in his groups sustained injuries. He is the only other person killed during American testing. In the USSR there were the two killed in the RDS-37 test that Sakharov reports on, but little is known about things like the Totsk test.

I noticed a small typo on the date of the New York Times November 17, 1952 issue, where below it is identified as from November 11th 1952. Fantastic blog, keep up the great work.

Eli Tennent

Thanks!