Today, November 7, is the first anniversary of the launching of this site. It’s gone by pretty quickly for me. I think I am allowed to do a meta-blogging post on this day, am I not? Don’t worry, I’ll include a few cool pictures, so you can skip the meta if you want to.

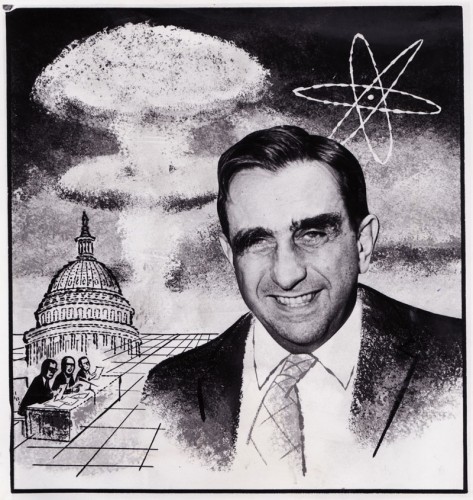

The grooviest Edward Teller graphic, ever? Yes, I bought this on eBay — it’s an AP photo from July 1959. Caption on the back: “Dr. Edward Teller, who played a leading role in the development of both the atom and hydrogen bombs, feels that Russia will be the unquestioned leader in the scientific field in 10 years. He believes that it is inevitable that Russia should take the lead because educating a scientist is a long process and the Soviets currently are training more scientists than the United States. This photo-drawing by AP Newsfeatures artist Dick Hodgins Jr. symbolizes Dr. Teller’s work with the atom and also his many controversies with Congress.”

I started the blog, in part, as a way to stretch out my mental limbs in a public way, having previously spent 7 or 8 years thinking about the history of nuclear weapons in relative isolation (which is to say, in an Ivy-clad cloister). I had hoped that the blog would be a forum for me to interact with new people, especially those from different fields or different vantage points in life, and to also work out — through writing — various little thoughts or preoccupations of mine that had accumulated over the years. It also was meant to be somewhat of an outlet for cool things that really can’t fit into the narrative of the book I am working on. In all of these things, it has been, for me anyway, fairly successful. I have a whole host of new contacts in a variety of communities (and over a fairly wide political range, I’ve found), and I’ve found that blogging regularly has helped me break out of some of overly-academic preoccupations that had been shaping my work and thinking.

As I know some people have noticed, I started with a much heavier blog schedule (three posts a week) and have since stretched that out a bit (one post a week). The initial burst was part of making sure that I really “bought in” to the idea, by investing a lot of my own time into it, and I also wanted to build up a store of content that would give people a pretty clear idea of the sorts of things I was interested in. Lately I’ve slowed it up, both so that I could make some more room in my schedule for other things (like writing that aforementioned book, which is coming along nicely), but also so I could spend a little bit more time on the posts, making them more like short essays than “look at this document/photo” posts. For those who prefer the latter types of posts to the former, don’t worry — I’ll probably start alternating them again when I have a little more time in my schedule. This is post 136.

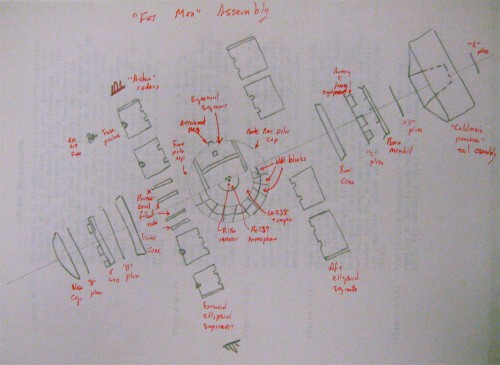

Original drawing by the late Chuck Hansen showing the assembly of the “Fat Man” nuclear bomb, used as a reference for the more sophisticated technical drawing that appears in his U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History. From the Chuck Hansen papers, National Security Archive.

By I think any standards, this has been a very positive experience for a new academic blogger, much less an historian of science blogger. (In my heart of hearts, I’d love to call what I do here a form of creative non-fiction, as opposed to “blogging,” but there are conventions.)

Much of the traffic I received was driven not by my sterling content, but by that funny creature, the NUKEMAP. It was not my expectation that it would get so crazy and drive so much traffic to the blog itself, which is still does on a regular basis. Before starting the NUKEMAP, the blog had around 2,600 unique visitors and 9,300 page views which felt very large for someone whose normal audience came from specialist journals and conference talks. Since its launching, the NUKEMAP itself attracted around 1,500,000 unique visitors and over 1,900,000 page views. It’s over 8 million “detonations” by my count this morning.

Of those visitors for the map, a small number go from there to visit the blog. A small number of 1.5 million though is a relatively large number in human terms — over 30,000 people. And some number of those become regular readers. So it’s been a nice “feeder” of traffic into the site, in and of itself, and the blog itself gets around a thousand hits a day as its “normal” traffic, because of this. Which is bananas, even if it is still small potatoes in the world of blogs, much less the world of adorable kittens and puppies on the Internet.

Microphotograph showing alpha tracks from plutonium particles in a sample of crushed ice taken from the site of the 1968 Thule, Greenland, B-52 crash. From “Project Crested Ice: A Joint Danish-American Report on the Crash Near Thule Air Base on 21 January 1968 of a B-52 Bomber Carrying Nuclear Weapons,” (February 1970), page 61.

There have been a few, non-NUKEMAP posts that have been read by a lot of people. Some of these reasons are obvious — i.e., they were featured on NPR or elsewhere — but some of them have been surprises to me. The top non-NUKEMAP posts have been:

- Beer and the Apocalypse (9/5/2012) – 17,800 pageviews

- Rare Photos of the Soviet Bomb Project (7/27/2012) – 13,400 pageviews

- The Sound of the Bomb (7/13/2012) – 11,800 pageviews

- Hiroshima at 67: The Line We Crossed (8/6/2012) – 3,800 pageviews

- Mortuary Services in Civil Defense (2/29/2012) – 2,900 pageviews

- The Faces of Project Y (8/31/2012) – 2,000 pageviews

#1 and #3 were on NPR, so no surprise there. #5 was linked to from #1, so that’s probably its boost. #4 was an anniversary, and people are into those. #6 came with a little app, which helped. But #2 was just pure unadulterated interest in weird photos of the Soviet bomb project, circulated primarily through social media. Pretty neat.

Aside from the very popular ones, here are a list of posts I really enjoyed writing and documents I really enjoyed sharing. I put them here, in no particular order, just in case you missed them (or were new here) and didn’t want to wade through everything:

- War from Above, War from Below (1/2/2012)

- Edward Teller’s “Moon Shot” (12/12/2011)

- Bullseye on Washington (12/30/2011)

- Do We Want Another Manhattan Project? (4/2/2012)

- Ol’ Blue Eyes (5/4/2012)

- What if Truman Hadn’t Ordered the H-bomb Crash Program? (6/18/2012)

- Targeting the USSR in August 1945 (4/27/2012)

- The First Atomic Stockpile Requirements (5/9/2012)

(Though, if you do want to wade through, I recommend using the Post Archives page, which is arranged via a custom script I wrote to be especially browse-able.)

The mushroom cloud of shot Franklin of Operation Plumbbob rises over a blimp at the Nevada Test Site, June 1957. The shot was a fizzle — only 140 tons of TNT, predicted yield 2 kilotons. From the DOE’s Nevada Site Office. Would it be crass of me to mention that a cleaned-up version of this photo is included in my 2013 Nuclear Testing Calendar? Only $19.99, all (meager) profits support the blog…

Looking over my past posts, I’ve found myself surprised by the themes that I keep coming back to. My academic work, and the aforementioned book-in-progress, is mostly concerned with unearthing the origin of practices and contexts of secrecy. In many ways it is a very traditional historical approach: look for periods of stability, look at what jars them into a periods of uncertainty, then look at what gels it back into a period of stability again. Repeat. It’s interesting stuff to research and write, to be sure — especially since most narratives of nuclear secrecy posit (implicitly or explicitly) a period of general stability from 1939 to the present, which just isn’t what I’ve found. Things have been much more up in the air, much more rocky, much more subject to change than you’d think from reading the “standard narratives” of the bomb. Moreover, there is a delicious little methodological point buried in it: the apparent homogeneity of the nuclear secrecy regime is in fact an artifact of the nuclear secrecy regime — its internal debates, challenges, and fractures were often hidden out of sight.

In my work on the blog, though, what I find myself preoccupied with is recapturing the qualitative experience of the bomb and its people. I’m fascinated with how lost history can be for those of us in the present, and how taking the time to reconstruct it, as it was lived and experienced at the time — and not how it necessarily has been handed down to us in neat, edited narratives of either triumph or disgrace — opens up such a rich, unusual, and often surreal world.

So I’m interested in how nuclear explosions sound, and how people who saw them described them, and how people planning to use them thought they could be really used, how they sketched them on the backs of steno pads, and how they danced across the headlines, and how the people who made them looked, even what color their eyes were, and how hard it is to imagine the size of a mushroom cloud. I am enraptured by the visual content of these times, and what direct access it seems to give us to the eyes of the long dead as they gaze upon horrible maps or bizarre security videos or the emblems of the atomic institutions or even just one another’s hairstyles.

A hauntingly grim painting that I’d love to know more about: “Atomic Landscape (Japanese Burial Detail),” Nagasaki, Japan 1946, by Robert Graham. From the U.S. Army Center of Military History.

I’ve always known that I was interested in such things, as a hobby, but I had never tried writing any of that down before, this obsession with the wonder of it all (to tap a phrase of James Ellroy’s). My enthusiasm for such things is sometimes hard to articulate without me sounding like a madman, because the “such things” in this case are monstrous nuclear weapons or other disturbing legacies of the nuclear age. Some of my early NUKEMAP interviews came off wrong, I felt, for this reason.

But I’ve learned to live with it, in a sense. There’s no point in pretending I don’t find this stuff fascinating, even if it is macabre. I can’t hide it; the answer is not to pretend to be disinterested, but just to try to be more thoughtful. That’s my responsibility, if I don’t want to look like I’m out of my mind, and if I don’t want to trivialize a lot of suffering and potential suffering. The blog has pushed me in that direction very forcefully, and that, at least as much as everything else, has been worth the payoff. One year down — here’s to the next year.

Internet years (IY) are shorter the calendar years (CY). During the dot-com boom, 7 IY = I CY, like dog years. Now that things have slowed down a bit, it’s more like 4 IY = I CY. So happy fourth anniversary, Restricted Data!

Great year! Looking forward to the next! Best, Kathy

Congratulations on one year, Alex!

Still hoping you’ll do a post on gaseous thermal enrichment one of these days

I’d be interested to know if, when and how any ideas about *molten* diffusion pop up in your reading.

Congratulations and thank you for maintaining this amazing site.

Congratulations! I love your post and share your enthusiasm for the simultaneous horrific/hilarious nature of so much surrounding the atomic bomb. You find such terrific stuff…and even as I type I am enjoying my morning coffee in your AEC mug. Looking forward to the next year of Restricted Data!

Small correction: that’s an actual powered blimp, not a barrage balloon. Barrage balloons didn’t have control cars, used inflatable fins not rigid ones (you need the rigidity since you’re using them as actual control surfaces) and were moored by just winching them down and partally deflating them, not using a mooring mast (that tetrahedron in the shot is a mooring mast).

And congrats on Year One — love the blog.

Ah, you are right. There are others in the same series that are barrage balloons and I rattled off the caption too fast…

Congrats on Year #1…it’s been both entertaining and edifying to read!

Thanks for your blog and congratulations on a year of posts from an amateur Cold War and nuclear history maven.

Congratulations! I was in the TWAA (and associated) business for 20 years. I love the hearing the stories and history from this side.

Congratulations! I would say your blog has been a great success, and I look forward to following it for another year. It has been an inspiration to me, and hopefully I’ll get the “Comedo Ergo Sum” food and STS blog going soon. Although it is a challenge balancing blogging, book-drafting, and early career duties. You’re an Übermensch!

Great work, Alex. May people continue to come for the destruction but stay for the history

Fascinating stuff, well done and thank you.

Great job Dr. Wellerstein. I’ve enjoyed the blog immensely and look forward to many more enjoyable hours spent here.

I am one who ‘found this site’ from the Nuke Map. I explored the limitations of the modeling, including one configuration which predicts the destruction of the Milky Way Galaxy, and a part of Andromeda.

Fun and interesting stuff.

I’m sure you’ve mentioned this in a blog post, but there’s something — shall we say ironic? Strangely edifying? — about wanting to share so much information about secrecy. I don’t remember when I first found this site, but I’m glad that I have, and I hope your future posts continue to be as informative and provocative as this first year’s. This is by no means a dead or esoteric topic reserved for academics only.

Alex,

Add my late congrats to Year 1! Belated, as I’ve been consciously avoiding the blog because it’s such an inspiration to comment, but I have this diss staring me down, so needed to focus. However, visited to check a citation and thought I’d say that your work here is of great value across a number of fields of interest. All that secrecy hid complexity, which becomes all that more obvious with each new finding in the archive. Looking forward to Year 2.