I’ve been on the road all this week, so there’s not too much of a post today! (The one last week was double-sized, though.) But I thought I’d share some interesting images that have captivated me over the last week or so.

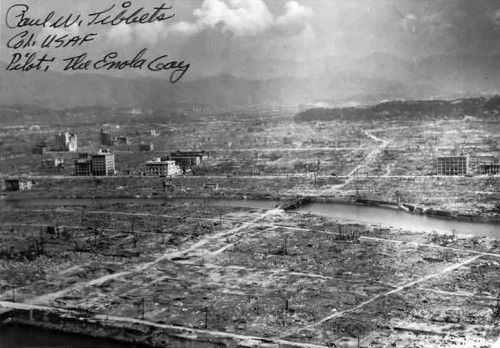

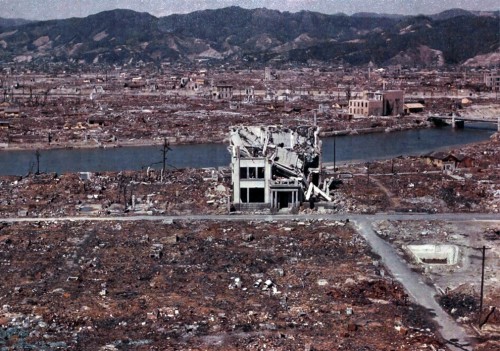

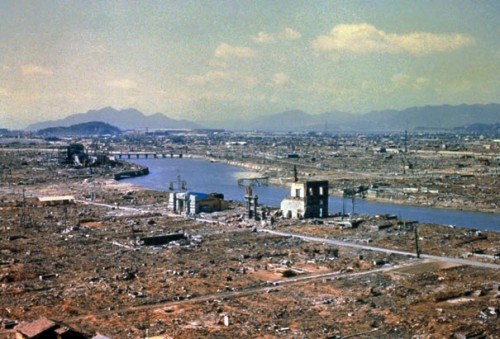

Most of the photos we are familiar with of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are black and white. The effect is one of a dusty, barren landscape — they look like abandoned cities on the moon. On top of that, almost all photos of the cities from the ground were taken after the bodies had been cleaned up and the streets cleared — most were taken no earlier than late September 1945, and many of the “classic” ones are actually from mid-to-late 1946, a year or so later. The net effect is that the cities were somehow neatly “vaporized.” This is a false impression.

Color photographs of the city, however, are far more striking. What was a city of dust now looks like a city of rubble. It becomes, in some unconscious way, more believable, more recent, less distant. It becomes more “real.”1

The effects of the bomb also become a bit more clear, though there is still a lot missing. The atomic bombs used during World War II killed most of its victims by burning and crushing them — the classic medieval tortures, made wholesale by technology but not much more modern. (Only about 15-20% of the people at the cities died truly “modern” deaths, from the radiation effects.)

The above photograph is of Hiroshima, apparently taken in March 1946 — some eight months after the bombing. You can tell a lot has been cleaned up: the roads, for example, are very clear. There are no obvious corpses. A few reinforced buildings are standing, but not much else is. There are some telephone or electricity poles up; I don’t know whether those were added after the attack, or were somehow still standing despite it (blast effects can be complicated).

The photo above is labeled as being of Hiroshima in the autumn of 1945. Superficially, when compared to the one before it, one thinks that the damage looks a lot lighter. There are a lot of poles and trees and a few shack-like structures in the foreground, and some factory-looking buildings in the background. But there’s still a lot of rubble — a lot of places that just aren’t there anymore. (I’m a little suspicious about whether this photo is identified correctly, to be honest.)

The above photograph was taken by the photographer J.R. Eyerman sometime in the fall of 1945. It’s a rare color view from the ground, as opposed to being from aircraft or from a high vantage point. It’s a vivid look at the twisted jungle of pipes, bricks, concrete, wood, trees, and other unidentified objects. Imagine the struggle of trying to make your way through that.

Another of Hiroshima from March 1946. Compare it to the one above, and how different a perception one has. It’s not that one of these is wrong, per se; they’re both of Hiroshima, and they both give away a different sense of the damage. In trying to get a sense of scale for these things, I find mixing up the modes of perception to be pretty important. One needs to understand what this looks like at the ground level, but then one needs to realize the extent to which that damage applied.

The above two are both of Nagasaki from around October 1945. Again, notice the almost capricious nature of this kind of damage: some of those trees look not so badly off, next to structures that have collapsed to the point of non-identification. The presence of people also lets you get a sense of the scale from the human point of view. A big ruinous mess.

This is listed as the damage outside a school in Nagasaki, taken just a few weeks after the bombs were dropped. Without knowing what this looked like before the attack, it’s hard to get a sense for what we’re looking at, but it appears the windows of the school are probably all blown in (there isn’t any glare or reflection), and those are some pretty big trees to see snapped about.

Hiroshima’s financial district, date unknown. Again, note the apparent capriciousness of the damage. The truth is, the construction of the buildings in question matters quite a bit. But don’t be too fooled — being inside a burning concrete building whose windows are blown in isn’t that great. You can tell the one in the middle has no remaining glass and some ominous-looking charring around the windows.

And here is one of the Hiroshima Gas Company and the Honkawa Elementary School. I think the latter really emphasizes the horror of “strategic” bombing, where burning elementary schools become acceptable as “collateral damage.” The famous dome at the upper right hand corner of the photo was directly underneath the explosion; the school was about 800 feet from there.

There are two ways you can go wrong in making sense of the scale of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The first is to see the bombs as instant vaporizers, to see the bombs as Everything Killers that just zap cities out of existence. This isn’t the case. They kill by crushing and burning and irradiating. They don’t turn you to dust. They don’t freeze you and turn you into a stop-motion skeleton, like in The Day After. For some, death was instantaneous, but for a lot of others, it was a much more protracted affair.

The other way to misunderstand it is to downplay it. Ah, a number of large buildings survived! It’s not so bad, then, right? Maybe the whole nuke thing has been exaggerated! Well, unless you are, you know, not in one of those buildings, and even if you are, it’s a pretty awful thing. Yes, you can approximate the city-wide effects of early atomic bombs with a fleet of conventional bombers dropping napalm — which personally I consider just as much a weapon of mass destruction as anything else, and yes, napalming cities is “conventional” in the sense that it is not a nuclear, biological, or chemical weapon, but let’s not forget that it’s not exactly an everyday occurrence. But being napalmed is not exactly a walk in the park for those being bombed, either.

So what’s the right view? An ugly, troublesome, disturbing one; right between those extremes. The atomic bomb was a weapon used to inflict tremendous human suffering. (This is true whether you think its use was justified or not.) If an atomic bomb were to go off over your city, the damage would be horrifying, the death toll staggering. But it’s a level of destruction that people should try to appreciate for what it is — a realistic possibility, not a clean science-fiction ending or a blow to be shrugged off.

That’s the perception I’m always searching for. The color photographs add a little bit to that, to keep one from the misconceptions, to keep one from seeing these wrecked cities as sanitary piles of dust.

- These come from here and there on the Internet, but two very nice galleries I got a number of them from are here, here, and here. I’ve done some color correction on the photos, which understandably have faded a bit over time. [↩]

I have always wondered how the lack of immediate and ‘grotesque’ photographs have shaped the view of the Atomic Bomb in use versus incindiary bombings.

There are plenty of horrific documentation of Dresden and other cities.

But since most of the photographs of Hiroshima/Nagasaki are long after most of the dead were removed, it gives the false illusion that most of the dead simply were vaporized and disappeared.

The myth is that it is a ‘clean’ and instant death for all involved, with a minimum of suffering. A sterile and precise death, so to speak.

It seems clear to me that the last picture shows exactly the same building as the second picture, except from a location a bit to the left as well as from ground level, and that the latter was after a lot of cleanup was done.

Since there a lot of “immediate” pictures of dead and dying people, I wonder if the human injuries were documented in more detail, more likely to be released for some reason, or if there are many others of property damage buried in archives no on knows about (like the color film and photos from WW II that keep turning up). My impression is that the Strategic Bombing Reports were extremely detailed and must contain a mere sampling of the observations made at the time, but perhaps unused images were discarded.

To help dispel any “false illusion that most of the dead were vaporized and disappeared” see the photos taken by Yosuke Yamahata in the days after the bombing of Nagasaki. book of his photos (I think it has gone out of print) shows terrible images of the deaths and the dying (literally).

There is a ghastly collection of photos at Canada’s Cold War Museum, located in Carp Ontario, just outside of Ottawa Ontario. They are mostly taken in the first few days after the attack. I have never seen them published elsewhere. The museum is located at the ‘Diefenbunker’ named after the Canadian Prime Minister of the day. It’s a four story bunker designed to shelter the government in the event of soviet attack.

[…] Link. Medieval methods with atoms. […]

I don’t know if you were ever aware of a campaign by the Japan Broadcasting Corporation in 1974 that solicited bomb survivors to send in graphic recollections of their ordeal.

I had found this campaign after innocuously searching for images of “Fire Cisterns” on Google–which now connotes terrible things within my conscience.

They aren’t photos, and they were drawn 19 years after the fact, but I believe they fill in those qualitative experiential gaps you are looking for that even photographers who came in to town soon after could not depict–that is, the scene of the entire city in flames, the streets and rivers choked with thousands of corpses, people cremating their relatives, picking maggots, and watching people die from radiation poisoning. The recollections span a wide age range, from toddlers to the middle aged. It reminded me of Grave of the Fireflies and Barefoot Gen, but as the submissions aren’t dramatizations they managed to hit me with more gravity even though the above mentioned were written by fire and atom bomb survivors.

Fascinating! Thanks. I had seen some of the images but not realized their provenance.

On your question of street poles, what the photos show is likely a mix of poles that survived the blast and poles hastily erected soon after in order to restore communications and power to the city. The Electric Railway working with the military in particular managed to resume electric streetcar services in several days Today, Hiroshima still operates two streetcars that survived the bomb.

If you are still curious, the Hiroshima station of the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation has done this graphic recollection campaignmore than once. I’m thinking this will likely become a common ritual as the urge to have the aging generations tell their stories becomes more acute.

Excellent photos and well thought out comments. Thank you for hosting such a non-confrontational site.

I have recently returned from visiting Hiroshima and while there visited the museum (worth a visit) these pitures show the absolute devastation of the city not the people. I like many people believed that the bomb vaporised people and consoled myself with the fact that ‘at least they died quickly’. This was not the case and when you read the testament of mothers/fathers whose children returned from school (800m from the blast point) in immense pain and suffered cruel painful deaths only then do you understand the complete devastation the bomb caused. I only hope a bomb of this magnatude is never used again.

[…] Image: Hiroshima in the fall of 1945. […]