In part of the “make this blog actually work again” campaign, I’ve changed some things on the backend which required me to change the blog url from http://nuclearsecrecy.com/blog/ to https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/. Fortunately, even if you don’t update your bookmarks, the old links should all still work automatically. It seems to be working a lot better at the moment — in the sense that I can once again edit the blog — so that’s something!

In all of the new NUKEMAP fuss, and the fact that my blog kept crashing, I didn’t get a chance to mention that I had two multimedia essays up on the website of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. I’m pretty happy with both of these, both visually and in terms of the text.

The first was published a few weeks ago, and was related to my much earlier post relating to the badge photographs at Los Alamos. “The faces that made the Bomb“ has so far proved to be the one thing I’ve done that people end up bringing up in casual conversation without realizing I wrote it. (The scenario is, I meet someone new, I mention I work on the history of nuclear weapons, they ask me if I’ve seen this thing on the Internet about the badge photographs, I answer that I in fact wrote it, a slight awkwardness follows.)

Some of the badge photographs are the ones that anyone on here would be familiar with — Oppenheimer, Groves, Fuchs, etc. But I enjoyed picking out a few more obscure characters. One of my favorites of these is Charlotte Serber, wife of the physicist and Oppenheimer student Robert Serber. Here’s my micro-essay:

Charlotte Serber was one of the many wives of the scientists who came to Los Alamos during the war. She was also one of the many wives who had their own substantial jobs while at the lab. While her husband, Robert Serber, worked on the design of the first nuclear weapons, Charlotte was the one in charge of running the technical library. While “librarian” might not at first glance seem vital to the war project, consider J. Robert Oppenheimer’s postwar letter to Serber, thanking her that “no single hour of delay has been attributed by any man in the laboratory to a malfunctioning, either in the Library or in the classified files. To this must be added the fact of the surprising success in controlling and accounting for the mass of classified information, where a single serious slip might not only have caused us the profoundest embarrassment but might have jeopardized the successful completion of our job.” Serber fell under unjustified suspicion of being a Communist in the immediate postwar, and, according to her FBI file, her phones were tapped. Who had singled her out as a possible Communist, because of her left-wing parents? Someone she thought of as a close personal friend: J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Charlotte was also the only woman Division Leader at Los Alamos, as the director of the library. She was also the only Division Leader barred from attending the Trinity test — on account of a lack of “facilities” for women there. She considered this a gross injustice.

What I like about Charlotte is not only that she highlights that many of the “Los Alamos wives” actually did work that was crucial to the project (and there were scientists amongst the “wives” as well, such as Elizabeth R. Graves, who I also profiled), and that the work of a librarian can be pretty vital (imagine if they didn’t have good organization of their reports, files, and classified information). But I also find Charlotte’s story amazing because of the betrayal: Oppenheimer the friend, Oppenheimer the snitch.

I should note that Oppenheimer’s labeling of Charlotte was probably not meant to be malicious — he was going over lists of people who might have Communist backgrounds when talking to the Manhattan Project security officers. He rattled off a number of names, and even said he thought most of them probably weren’t themselves Communists. This, of course, meant that they got flagged as possible Communists for the rest of their lives. Oppenheimer’s attempt to look loyal to the security system, even his attempts to be benign about it, were terrible failures in the long run, both for him and for his poor friends. Albert Einstein put it well: “The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves a woman who doesn’t love him—the United States government.”

The other one I want to highlight on here is that of Kenneth T. Bainbridge. Bainbridge was Harvard physicist and was in charge of organizing Project Trinity, the first test of the atomic bomb in July 1945. It was a big job — bigger, I think, than most people realize. You don’t just throw an atomic bomb on top of a tower in the desert and set it off. It had a pretty large staff, required a ton of theoretical and practical work, and, in the end, was an experiment that, ideally, destroyed itself in the process. Here was my Bainbridge blurb:

During the Manhattan Project, Harvard physicist Kenneth Bainbridge was in charge of setting up the Trinity test—afterward he became known as the person who famously said: “Now we are all sons of bitches.” Years later he wrote a letter to J. Robert Oppenheimer explaining his choice of words: “I was saying in effect that we had all worked hard to complete a weapon which would shorten the war but posterity would not consider that phase of it and would judge the effort as the creation of an unspeakable weapon by unfeeling people. I was also saying that the weapon was terrible and those who contributed to its development must share in any condemnation of it. Those who object to the language certainly could not have lived at Trinity for any length of time.” Oppenheimer’s reply to Bainbridge’s sentiments was simple: “We do not have to explain them to anyone.”

I’ve had that Bainbridge/Oppenheimer exchange in my files for a long time, but never really had a great opportunity to put it into print. To flesh out the context a little more, it came out in the wake of Lansing Lamont’s popular book, Day of Trinity (1965). Bainbridge was one of the sources Lamont had talked to, and he gave him the “sons of bitches” quote. Oppenheimer’s full reply to Bainbridge took some digs at the book:

“When Lamont’s book on Trinity came, I first showed it to Kitty; and a moment later I heard her in the most unseemly laughter. She had found the preposterous piece about the ‘obscure lines from a sonnet of Baudelaire.’ But despite this, and all else that was wrong with it, the book was worth something to me because it recalled your words. I had not remembered them, but I did and do recall them. We do not have to explain them to anyone.”

The “obscure lines” was some kind of code supposedly sent by Oppenheimer to Kitty to say that the test worked. In Bainbridge’s files at the Harvard Archives there is quite a lot of material on the Lamont book from other Manhattan Project participants — most of them found a lot of fault with it on a factual basis, but admired its writing and presentation.

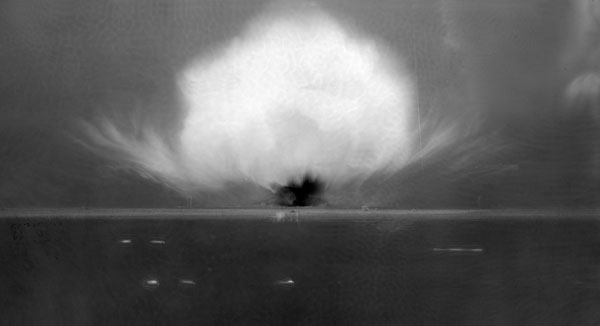

Bainbridge makes for a good segue into my other BAS multimedia essay, “The beginning of the Bomb,” which is about the Trinity test and which came out just before the 68th anniversary, which was two weeks ago. It also was somewhat of a reprise of themes I’d first played with on the blog, namely my post on “Trinity’s Cloud.” I’ve been struck that while Trinity was so extensively documented, the same few pictures of it and its explosion are re-used again and again. Basically, if it isn’t one of the “blobs of fire” pictures, or the Jack Aeby early-stage fireball/cloud photograph (the one used on the cover of The Making of the Atomic Bomb), then it doesn’t seem to exist. Among other things related to Trinity, I got to include two of my favorite alternative Trinity photographs.

The first is this ghostly apparition above. What a strange, occult thing the atomic bomb looks like in this view. While most photographs of the bomb are concerned about capturing it at a precise fraction of a second — a nice precursor to the famous Rapatronic photographs of the 1950s — this one does something quite different, and quite unusual. This is a long exposure photograph of several seconds of the explosion. The caption indicates (assuming I am interpreting it correctly) that it is an exposure of several seconds before the explosion and then two seconds after the beginning of the detonation. Which would explain why there are so many pre-blast details available to see.

The result is what you see here: a phantom whose resemblance to the “classic” Trinity explosion pictures is more evocative than definite. And if you view it at full size, you can just make out features of the desert floor: the cables that held up the tower, for example. (Along with some strange, blobby artifacts associated with dark room work.) I somewhat wish this was the image of “the atomic bomb” that we all had in our minds — dark, ghastly, tremendous. Instead of seeing just a moment after the atomic age began, we instead see in a single image the transition between one age and the next.

Most of the photographs of Trinity are of its first few seconds. But this one is not. It may be the only good photograph I have seen of the late-stage Trinity mushroom cloud. It is striking, is it not? A tall, dark column of smoke, lightly mushroomed at the top, with a larger cloud layer above it. “Ominous” is the word I keep coming back to, especially once you know that the cloud in question was highly radioactive.

One of the things I found while researching the behavior of mushroom clouds for the NUKEMAP3D was that while the mushroom cloud is an ubiquitous symbol of the bomb, it is specifically the early-stage mushroom cloud whose photograph gets shown repeatedly. Almost all nuclear detonation photographs are of the first 30 second or so of the explosion, when the mushroom cloud is still quite small, and usually quite bright and mushroomy. The late-stage cloud — about 4-10 minutes, depending on the yield of the bomb — is a much larger, darker, and unpleasant thing.

Why did we so quickly move from thinking of the atomic bomb as a burst of fire into a cloud of smoke? The obvious answer would be Hiroshima and Nagasaki, where we lacked the instrumentation to see the fireball, and only could see the cloud. But I’m still struck that our visions of these things are still so constrained to a few examples, a few moments in time, out of so many other possibilities, each with their own quite different visual associations.

Here’s a framegrab of Charlotte Serber, cigarette in hand, discussing Hugh Bradner’s movie camera with her horse. The Serbers went camping in the mountains with Marge and Hugh Bradner, Robert Wilson, and Jane Wilson. You, Alex, introduced me to Bradner’s home movies after they were released by Los Alamos last year.

Oh, man, that old thing about not having “facilities” for women!

In the mid-1970s, I had an experiment on plutonium that I wanted to do. That required the gloveboxes at DP Site. But there wasn’t a change room for women. They were getting one ready, a trailer outside the building that would never pass today’s muster. But it wasn’t ready. And it wasn’t ready. And it wasn’t ready. Sorry, it just isn’t ready.

So I was getting more and more impatient to do the experiment, and one day I stood outside the door to the men’s change room and said, “Gee, I guess I’ll have to suit up in the men’s change room.” The next day, the women’s change room was ready. And I did the experiment. Got a paper out of it, too.

In contrast, when I visited the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site a few years ago, my hosts had an immaculate bathroom prepared especially for me.

[…] “A thousand simultaneous suns”: a long-exposure shot of the Trinity test. […]

Photos of nuclear tests: In 1984 I was editing a music video for Danny Elfman’s band, Oingo Boingo. We had ordered some stock footage of a hydrogen bomb test to project on the background of a beach set while the band played “Nothing Bad Ever Happens To Me.” When I got the footage I rolled up to the first frame of the explosion and the 35mm film just went totally clear, no frame line, no nothing- clear leader. I thought there had been a mistake or a problem at the lab. 35mm film goes through the camera at 90′ per minute. I had to crank the rewinds for a long time before an image finally began to appear on the film. It scared the hell out of me. In the 1950s I had been taught to “duck and cover” and not to look at the explosion outside. What a joke. The most chilling photograph of a nuclear explosion I have ever seen was that seemingly endless strip of clear film!

That’s a wonderful anecdote — thank you!