Richard Nixon was a President so utterly fascinating that if he didn’t exist, historians would have had to invent him. He was both clever and odious, politically appealing but personally unpleasant. Flawed enough that he managed to pointlessly lose the Presidency because of his insecurities, his desire for even more of a landslide than he already had. Anti-semitic, homophobic, racist — but also canny, both with regards to foreign policy and American domestic politics. And what a gift for historians of the future, that he compulsively recorded himself saying awful things? It’s almost too much to be believed, the truth being much more stranger than any fictionalized President could be.

We don’t talk much about Nixon and the bomb, which is perhaps a little odd. The Nixon years were those of détente, which has something to do with it, and there were no “close calls” or fiery public rhetoric about the bomb. Nixon only rarely shows up personally in my work; he didn’t appear to get involved with nuclear matters to the degree that Kennedy or Eisenhower did, for example, much less those like Reagan or Truman.

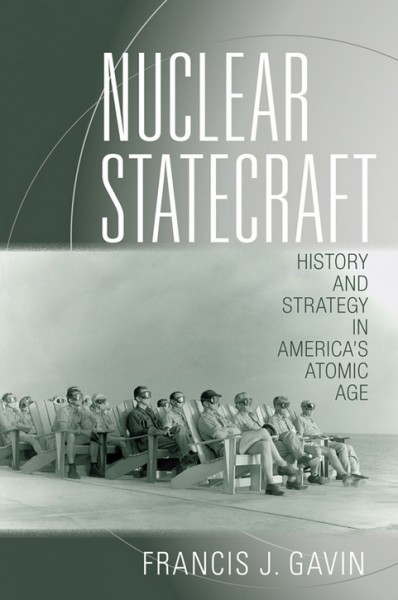

But this is an oversight. Nixon and the bomb is an immensely interesting subject, as I recently learned. Last week I was at a nuclear history/policy conference hosted by Francis Gavin, among a few others, that was itself immensely interesting and fruitful. Before going, I thought I should get around to reading Gavin’s latest book, Nuclear Statecraft: History and Strategy in America’s Atomic Age, since he had bothered to invite me and all.1

It’s incredibly interesting as a book of history written with a mind towards those who care about policy. Each chapter tackles a major issue in nuclear history and gives a unique perspective or new findings on it. For example, the Kennedy and Johnston administrations get lots of credit for adopting a “flexible response” approach to nuclear targeting, but Gavin reports that while they gave speeches on this, in practice their war plans were little more flexible than Eisenhower’s, because privately they judged flexibility to be difficult and dangerous. That was new to me, and a nice point about the difference between public statements and official policy, and the trickiness of divining information about secret programs from the party line.

The chapter that really wowed me was on Nixon. Again, I hadn’t given Nixon and the bomb all that much thought. But Gavin points out that it deserves much more attention, because while on paper Nixon looked like an exemplary arms controller, but in private, he is revealed as a total maniac something much more complicated.

For his arms control cred, just consider that Nixon was the one who signed the SALT treaty, the ABM treaty, and the Biological Weapons Convention. He was also President when the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty was ratified, and when the SALT II talks began. Kind of a non-trivial list of treaties and agreements — an impressive record for any US President. But as Gavin puts it:

The documents, however, reveal that Kissinger and, especially, Nixon had a different notion of how nuclear weapons affected international relations. … Theirs was a realist view—they believed that world politics was driven, as it had been for centuries, by geopolitical competition between great powers. The “nuclear revolution” had not changed this core feature of the international system. In relations with the Soviets, the message to their opponents was clear: “Look, we’ll divide up the world, but by God you’re going to respect our side or we won’t respect your side.”2

As evidence of this, Gavin has lots of excerpts from conversations between Nixon and Kissinger about nukes and treaties. They are universally disdainful of arms control. While Nixon was beginning the bomb the hell out of Cambodia (one of his least popular policies), he remarked to Kissinger: “Looking back over the past year we have been praised for all the wrong things: Okinawa, SALT, germs, Nixon Doctrine. Now [we are] finally doing the right thing.” Which tells you a lot about Nixon’s worldview: what mattered to him, in the end, was winning in Vietnam. Full stop. Everything else was just a distraction.

As for arms control, Nixon told Kissinger that “I don’t give a damn about SALT; I just couldn’t care less about it.” On the kinds of technical matters that concerned security wonks, like the number of radars or missile interceptors, Nixon privately explained that “I don’t think it makes a hell of a lot of difference,” and that he thought the arms controllers were real chumps about this kind of thing. He opposed an anti-ballistic missile site in the nation’s capital because:

I don’t want Washington. I don’t like the feel of Washington. I don’t like that goddamn command airplane or any of this. I don’t believe in all that crap. I think the idea of building a new system around Washington is stupid.

Which you have to admit is sort of a novel argument against anti-ballistic missiles, right? Because you don’t actually like the nation’s capital that you’re President of. He dismissed the Biological Weapons Convention as “the silly biological warfare thing, which doesn’t mean anything,” as opposed to what he considered the really important stuff — again, the war in Vietnam.3

For Dick and Henry, treaties were just pieces of paper that would probably be violated the moment they proved less than useful for a state. Realpolitik, plain and simple. But they were not just flying by the seat of their pants. Their approach to international politics was, Gavin argues, coherent. It just didn’t give a lot of credence to the idea that nuclear weapons had any special importance with regards to international order, since they really didn’t think that they were going to get into a genuine shooting war with the USSR anytime soon. Worse, they thought that arms control successes could lead towards the Soviets attempting to take concessions elsewhere — that if they were “good” in one arena they could then get away with being “bad” in another.

But my favorite quotes are from Nixon about Vietnam. During a spring offensive by the North Vietnamese in 1972, Nixon told Kissinger:

We’re going to do it. I’m going to destroy the goddamn country, believe me, I mean destroy it if necessary. And let me say, even the nuclear weapons if necessary. It isn’t necessary. But, you know, what I mean is, what shows you the extent to which I’m willing to go. By a nuclear weapon, I mean that we will bomb the living bejeezus out of North Vietnam and then if anybody interferes we will threaten the nuclear weapons.

A week later, he continued to a somewhat horrified Kissinger:

Nixon: I’d rather use the nuclear bomb. Have you got that ready?

Kissinger: That, I think, would just be too much.

Nixon: A nuclear bomb, does that bother you?… I just want you to think big, Henry, for Christ’s sake! The only place where you and I disagree is with regard to the bombing. You’re so goddamned concerned about civilians, and I don’t give a damn. I don’t care.

Kissinger: I’m concerned about the civilians because I don’t want the world to be mobilized against you as a butcher.4

Yeesh. Which just goes to show, that Nixon’s realpolitik approach to nuclear weapons does seem to be slightly unhinged at times — that nukes were not necessarily off the table when he thought about the things he really cared about, at least when he was trying to get a rise out of Kissinger.

As for the NPT, Nixon opposed it during his election campaign, both because he felt treaties were by themselves unenforcible and because he thought there might be some American allies who could use their own nukes. (As a possible example of the kind of difficulty the NPT created, consider that Nixon was the one who helped formulate the pact with Golda Meir that involved Israel never admitting it possessed nuclear weapons so as to maintain good relations with the USA. The NPT put limitations on the US with regards to its Middle Eastern ally, which is not something Nixon would have been happy about.)

Lastly, there is the “madman” approach that Nixon and Kissinger cooked up — that Kissinger should convince the Soviets that Nixon was unhinged enough to start nuking if things went too sour in Vietnam or elsewhere. This is perhaps Nixon’s most significant engagement with the nuclear question, and it was all psychological, all ploy. And, as Gavin points out, of questionable effectiveness.

Gavin doesn’t defend Nixon’s position on nukes and treaties; he just points out that Nixon actually had a position, and that it was actually deeply at odds with his (mostly positive) public record. The reason Nixon felt free to sign so many agreements is in part because he didn’t take them very seriously. How’s that for an ironic twist? If you don’t think arms control treaties actually matter, then what’s the harm in signing a few more of them?

- Francis Gavin, Nuclear Statecraft: History and Strategy in America’s Atomic Age (Cornell University Press, 2012). [↩]

- Gavin, 108. [↩]

- Gavin, 109-110. [↩]

- Gavin, 116, with some of the rest of the quote filled out from elsewhere. [↩]

Highly recommend the Gavin book. Even though I’m way left of him, it’s one of my favorite nukes books ever.

Now that post was an awesome read. I am definitely reading the book.

—I would like some background: Nixon was V.P. under Eisenower, and that included the tactical nuclear weapons in germany.

—How did Nixon, at least as Veep, if not as President, view expanding the battlefield from nuking bases with 83 KT Mark Six Bombs to nuking Soviet tank columns with tactical nuclear weapons?

Damn, just when the world though it’s opinion of Nixon could not get any lower!

And love this blog, thank you.

If reality is stranger than fiction, I suppose it can be funnier than comedy. Those Nixon quotes are as entertaining as any found in doctor strangelove. Even your last photo of Nixon looks as zany as any of the characters in the movie.

I felt a little bad about using such a zany Nixon picture — I know as well as anyone how silly one can look if a random still is taken of you — but I figured I had enough “serious Nixon” photos to offset it. I find his official portrait at the top the creepiest, to be honest.

Alex,

The Gavin book sounds excellent.

In a Nuclear Notebook (Sep-Oct 2006) column in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists about threats to use nuclear weapons I wrote the following.

“Vietnam and the Madman Alert, October 1969: On the eve of a massive mining and bombing campaign against North Vietnam, President Richard Nixon ordered that nuclear forces be placed on higher stages of alert with the purpose of pressuring the Soviets and the North Vietnamese to make diplomatic concessions that might eventually bring an end to the war. “At the core of Nixon’s notions was a diplomacy-supporting stratagem he called the Madman Theory, or, as he and Bob Haldeman described it, ‘the principle of the threat of excessive force.’ Nixon was convinced that his power would be enhanced if his opponents thought he might use excessive force, even nuclear force. That, coupled with his reputation for ruthlessness, he believed, would suggest that he was dangerously unpredictable. The Madman Theory under girded not only his policy toward North Vietnam but also toward other adversaries, including the Soviet Union.”

The goal was to signal the Soviets but to keep it secret from the public. Only a tiny handful of U.S. civilian and military officials knew of Nixon’s order or why he was doing it. Beginning on October 13th, the Strategic Air Command placed 144 B-52s and 32 B-58 nuclear bombers and 189 KC-135 tankers on ground alert. This number, it was assumed, would be “discernible to the Soviets but not threatening in themselves” in the words of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Earle G. Wheeler. Other combatant commanders shifted their nuclear-capable aircraft from conducting routine training sorties to heightened combat readiness. Nuclear-capable air defense forces of the Alaskan and Continental Air Defense Commands also responded, as did various navy ships. All of this was designed to be kept secret from the public and from NATO officials. In an effort to get the Soviet’s attention, several SAC bombers, loaded with four or more nuclear bombs, flew continuously “over the frozen terrain of the Artic” in late October. With no fixed endpoint to the global demonstration it was decided that the readiness level would continue until there was an indication that the Soviets had taken notice. In the end, all of this muscle flexing had little effect. There is no documentary evidence that Moscow ever expressed concern. Nixon and Kissinger had hoped to pressure the Soviets into facilitating a Vietnam breakthrough but that proved illusory. They were unlikely to be pressured or bullied by Nixon and it is remains unclear how they interpreted it. Nevertheless, the failure of the show of force did not lessen the validity of the Madman Theory in Nixon’s mind. He “continued to believe that threats of force, military signaling, and alerts intimating nuclear threats were valid and necessary tools of diplomacy.”

Interesting, thoughtful discussion. On SALT, while Nixon didn’t care about the details, agreements like that were important to him; he had to have SALT and other agreements with Moscow in place during 1972, in time for re-election so he could burnish his reputation as a “peace candidate” (détente with China and Russia). On that statement, “A nuclear bomb, does that bother you etc” some of it sounds like he was saying it to needle Kissinger, with whom his relationship was becoming less comfortable, for all kinds of reasons. And Nixon liked to talk tough in private, maybe to let off steam, but he was not going to screw up his re-election, or even his historical reputation, by using nukes in Vietnam. No, he would find other ways to wreck his historical reputation!