After 10 years of effort, Cindy Kelly of the Atomic Heritage Foundation has managed to achieve the seemingly-impossible: she got Congress to agree to preserving several former Manhattan Project sites. I have worked with Cindy in the past and am so extremely proud of her and her organization, and am frankly amazed that she managed to get this through this impossible Congress.

I completely support this preservation, without reservations. I have seen in various places that there are people who think that preserving these sites might somehow lead to “glorification” of the atomic bombs. I find this an extremely un-compelling objection. The atomic bombs will be glorified, or not, whether you preserve the facilities that produced them. We have preserved far more heinous sites for the historical record, because preservation does not mean endorsement. In fact, preservation often can mean an opportunity to reflect upon the past, warts and all. And razing these sites — which is the other alternative — would not change one bit of their history, or how it is remembered. People who worry about the historical legacy of the atomic bomb should be happy these sites are going to be preserved, because in the future, when we are talking about how they should be contextualized and interpreted, everyone will have a place to put their own vision of these places forward.

To clear one thing up, nobody knows what the “interpretation” — the presentation materials, exhibits, what have you — associated with these sites will look like. That is still a long way down the road. The bill which created these sites, the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015, signed by President Obama in December, provides no guidance for interpretation, and, non-coincidentally, no funding for it. It merely sets the sites apart, giving the National Park Service the ability to claim custody of them from the Department of Energy. Part of the reason for wanting something like this is evident in the DOE’s destruction of K-25 — the DOE is not really about preservation, and if these sites are not being used by them, they are just as likely to destroy them as anything else.

The relevant section of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2015.

Interpretation funds will presumably come later. A few years ago I participated in an NSF-sponsored workshop related to the interpretation of these sites, in preparation for the possibility of this legislation passing. It was an extremely interesting experience, and I blogged a little about it at the time. My key take-away then was that almost everyone there had fairly similar ideas as to what good interpretation of the Manhattan Project would be — not a mindless glorification, or an equally problematic polemic, but something that would try to contextualize the Manhattan Project both within World War II and the Cold War. This includes both its relationship to the bombing of Japan, and questions about whether it was necessary or not, as well as its environmental and personal legacies.

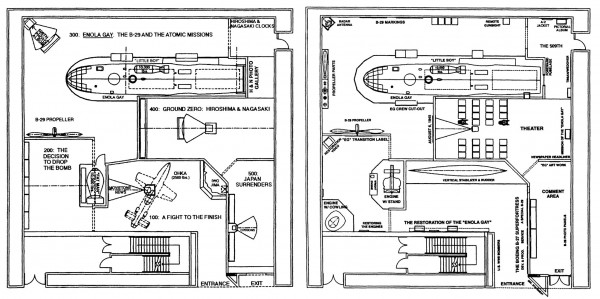

Obviously this is contested ground. I am hopeful that the NPS will reach out to historians, archivists, museum curators, and other stakeholders (including, but not limited to, veterans) when it develops its interpretation materials. Interpretation of the past in a public context can be incredibly controversial, of course. We all know of the 1995 Smithsonian Enola Gay controversy. Does this have an opportunity to turn out the same way?

At left, the floorplan of the planned Enola Gay exhibition; at right, the actual exhibition that aired: the retreat of the political into the refuge of the technical. From Richard H. Krohn, “History and the Culture Wars: The Case of the Smithsonian Institute’s Enola Gay Exhibition,” Journal of American History 82, no. 3 (1995), 1036-1063.

It’s not clear to me that it would. For one thing, this isn’t the mid-1990s, with all of its immediate post-Cold-War ambivalences, and its fierce battles over the historical memory of the still-living, mixed with the “Culture Wars” of the time. There are far fewer World War II veterans around than there were then, and the historical scholarship itself is not nearly as polarized around rigid ideological positions as it was then. On the whole, my feeling is that there is an increased willingness to acknowledge the complexities of both American and Japanese actions in the Pacific Theatre. There are ways of talking about this history that doesn’t make it seem like it endorses any particular political position on either World War II or the Cold War. The complexity of the historical events and questions being asked require this kind of complex presentation, if they are taken seriously. Very little in good history boils down to easy ideological stances.

Let’s hope that when it comes to interpretation, the NPS will feel emboldened enough to get a balanced text together, and that our politicians will not show themselves to be so frail and afraid of history as they did during the Enola Gay exhibition. I am personally optimistic — so much has changed since the 1990s, in terms of historical memory of the bomb, and we are getting to that place where enough time has passed that things are not so raw and recent. There is still a “Culture War,” to be sure, though the terms seem a little different than the mid-1990s. But in general, there is, I think, more of a middle-ground between the classic “revisionist” and “orthodox” views on the bomb, and this middle-ground is, I think, less problematic to those on both the left and the right. It will be interesting to see, as a preview, the various “70th anniversary of the bomb” overtures that will be made this summer, and how those resonate culturally. (A colleague of mine recently suggested that frankly the more interesting anniversary will be the 80th one, when there will be exactly zero living veterans still around.)

The Enola Gay today, in a relatively decontextualized display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s Udvar-Hazy Center. Via Wikipedia.

But even if things should get heated, even if old debates over the war and its conduct should bubble up, we should be glad for it. It is better to have a contested site than to have no site at all. We can always argue over the interpretation of the past, and we always will. We should see this as a new an invitation to a discussion, and reasonable people can disagree on key questions and issues, and let us hope that whatever controversies that come from it prove generative. We should keep the experience of the Smithsonian in mind when thinking about the creation of interpretative materials — for example, by making sure that many stakeholders are involved in the planning process, which will lead, at the very least, to fewer surprises down the line.

I look forward to participating in these future discussions. But we can only do that if we preserve the past in the first place, which is what this bill is trying to do. People who object that this bill will just result in the glorification of the past are being short-sighted about its intent and purpose, and making assumptions that, at the moment, are unwarranted. I don’t think there can be any question as to whether preservation is the right move, because the alternative — neglect and destruction — is no alternative at all.

Excellent analysis, with which I agree. I hope that the Manhattan Project can also be contextualized within scientific history: the remarkable progress in atomic physics in the 40 years prior to the war, without which there wouldn’t have been a bomb. Not to mention, what if there had been no WWII? What might nuclear history look like without it?

how about doing something with nothfield tinian?

In the popular memory, MANHATTAN is about the only place in the whole PROJECT that remains under-recognized.

As a child of the Fifties and Sixties, I already knew full well about the events in Chicago, New Mexico, Washington State and Oak Ridge.

But I thought Manhattan in the project name was merely a clever red herring , to throw people off from where the real action was happening.

I do hope the many sites in New York City area get more accord as this new Legislation unfolds…

The Atomic Heritage Foundation sells four very nice guidebooks about the Manhattan Project, one is dedicated to sites in Manhattan NY in addition to books Oak Ridge, Los Alamos, and Hanford.

Books

http://www.atomicheritagefoundation.com/category-s/100.htm

Detail on Manhattan NY

http://www.atomicheritage.org/location/manhattan-ny

This is excellent news and I can’t wait to see these sites protected and even more accessible

The NPS is not a stranger to preserving and interpreting the less idealistic and downright shameful parts of American history, here’s a few other of the more complicated National Park sites:

Sand Creek Massacre

http://www.nps.gov/sand/index.htm

Washita Battlefield

http://www.nps.gov/waba/index.htm

Little Bighorn

http://www.nps.gov/libi/index.htm

Big Hole Battlefield

http://www.nps.gov/biho/index.htm

Manzanar Japanese American Internment Camp

http://www.nps.gov/manz/index.htm

Minidoka Japanese American Internment Camp

http://www.nps.gov/miin/index.htm

Little Rock Central High School

http://www.nps.gov/chsc/index.htm

and they’ve gotten a start at interpreting some aspects of the Cold War already with the Minuteman Missile Site

http://www.nps.gov/mimi/index.htm

Great examples — thank you!

There is a train station in Florence, Italy. It was made in the 1930s under Mussolini. From the air, it looks like the “Fasci,” the symbol of the fascist state.

I have read that it looks like that to work with the railway lines, that were already that way, not because it had to be that way.

I wondered, did anyone consider tearing down the station that Mussolini commissioned? I guess that it would have been crazy to tear down a functioning train station in much destroyed post-war Italy, but it has been used for 70 odd years.

Clarification: I have read that the shape of the building was to match the railway tracks, not because the architect was told to make it match a ‘Fasci.’

It does look like a ‘Fasci,” and Mussolini ordered it made, though.

The B Reactor at Hanford in SE Washington, is already preserved and has public tours. There is an “Atomic Museum” at Kirtland Air Force Base, with replicas of the bombs dropped on Japan. I know of no controversy for these. A new public museum just opened near the Hanford Site, including history of the site construction and development, with no controversy.

I’m not sure this is the place to post this information –

From the Denver Post, December 25, 2014:

“Sanford Lawrence Simons, one of the scientists who developed the atomic bomb and later served time in prison for taking valuable souvenirs from it, died from cancer this month [Dec 2014] in Littleton. He was 92 years old.”

My Ex wife Marilyn is living in the same nursing facility in Littleton, CO where “Sandy” Simons was living when he died in December 2014. Apparently she and Mr. Simons became good friends, and had long chats. Knowing of my interest in WWII, Marilyn suggested to one of our sons that he send the obit to me. Subsequently, Marilyn’s sister told me that Mr. Simons ‘had a crush” on Marilyn.

The complete obit may be found here:

http://digital.olivesoftware.com/Olive/ODE/DenverPost/LandingPage/LandingPage.aspx?href=VERQLzIwMTQvMTIvMjU.&pageno=Mg..&entity=QXIwMDIwMw..&view=ZW50aXR5

If the hyperlink does not work I can include the entire obit in a new response.

bud Thompson

Deltona, FL

Regrettably, one important Manhattan Project site has been virtually unknown: Wendover Army Air Field in Utah, where the ordnance testing and development of the bombs was based. The 7 months of intensive work in conjunction with Los Alamos was conducted by the 216th Army Air Forces Base Unit (Special), which until two years ago had been unknown to atomic history. Cindy Kelly, President of the AHF, kindly invited my wife (a daughter of the 216th’s commanding officer) and me to record oral histories for AHF’s “Voices of the Manhattan Project” collection. As well, Alex selected two of my articles about the 216th for his 2013 and 2014 Bibliographies. There is an ongoing effort to restore some of Wendover’s facilities that is described on this website: http://www.wendoverairbase.com/

Specific dates when the 216th Army Air Forces Base Unit was formed and disbanded would be much appreciated.

Ross, thanks for your interest in the 216th. Unfortunately, specific dates for the 216th are obscure because there apparently were two versions of the 216th at Wendover. The period covering its role in the Manhattan Project has been documented in my two papers published in the 2012 and 2013 Winter issues of Air Power History, published by the Air Force Historical Association. That period probably roughly coincided with the command of their CO, Col. Cliff Heflin (my father-in-law), when the unit was designated 216th AAF BU (Special). Those dates were 19 January 1945 – 22 October 1945. Regrettably, the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell AFB in 2013 reported that, “For some reason, the histories for the 216th AAF BU goes to September 1944 and then does not pick up again until January 1946.” In my second paper, I speculate that the missing 216th records are due to the 1945 classification of the Ordnance section of the Smyth Report that remains to this day.

So, I assume that when the 216th was not designated “Special” coincided with the birth and death of Wendover as an active AAF/AF base, which I have not investigated.

I hope this is reasonably clear. If you’d like a copy of my two papers (both peer-reviewed) please send me your email address which I don’t see in this thread.

Here’s some photos of Wendover, they’ve made a lot of progress getting things cleaned up in the last few years

https://www.flickr.com/photos/rocbolt/sets/72157629901280091/

Kelly,

Thanks for the link. Jim Peterson is head of the Historic Wendover Airfield Foundation, which has slowly been raising money to restore the base, after having been shuttered for decades. Of interest, the final reunion of the 509th Composite Group will be held at Wendover this September.

—Odd thought: if some other country, say Japan, or Pakistan, were asked to put up the money for the preservation, would they insist on designing the exhibit?

Or, to use the most obvious list, Russia, the UK, France, Israel, People’s Republic of China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea?

I’m sure they would insist on having some say in it, but it is a moot point, since I doubt the NPS can take money from a foreign entity (I’m not sure they can even take money from private entities for something like this).

The V-Site was conserved back in 2007 or thereabouts, and there is some signage already posted. Whether or not the signage constitutes “interpretation” is unclear, and in any case the NPS will have the final say as to what stays and what goes.

The site is still behind the fence at Los Alamos, unfortunately.

http://www.crockerltd.net/v-site.htm

“Interpretation” in this context means all sorts of information meant to be given to the public. It can range from the very bare-bones (a sign, a pamphlet) to the much more elaborate (exhibits, tours, books). It is a complex issue because NPS doesn’t get a lot of money for this, and the professionals who produce this kind of material are not cheap, so it can vary a lot from site to site.

Historians and curators have often said that a frank approach to the horrors of the Pacific War has to wait until the veterans have died off, because it is still too upsetting for them. But when it comes to “middle-ground between the classic “revisionist” and “orthodox” views on the bomb”, the generation we are waiting to die off (or at least retire) is the Baby Boomers, for whom the revisionist version is too often an article of faith. The recent shift to the middle ground may be a sign that they are being replaced by Gen X historians armed with declassified documents.