Confession: I once told my students something I knew wasn’t true. It was during a lecture on the Space Race, on Sputnik 2, which carried the dog Laika into space in November 1957. I told them about how the Soviets initially said she had lived a week before expiring (it was always intended to be a one-way trip), but that after the USSR had collapsed the Russians admitted that she had died almost immediately because their cooling systems had failed. All true so far.

But then one bright, sensitive sophomore, with a sheen on her eyes and a tremble in her voice, asked, “But did they at least learn something from her death?” And I said, “oh, um, well, uh… yes, yes — they learned a lot.”

Which I knew was false — they learned almost nothing. But what can you do, confronted with someone who is taking in the full reality of the fact that the Soviets sent a dog in space with the full knowledge it would die? It’s a heavy thing to admit that Laika gave her life in vain. (In subsequent classes, whenever I bring up Sputnik, I always preempt this situation by telling the above story, which relieves a little of the pressure.)

A Soviet matchbox with a heroic Laika, the first dog in space. Caption: “First satellite passenger — the dog, Laika.” Want it on a shirt, or a really wonderful mug?

I’m a dog person. I’ve had cats, but really, it’s dogs for me. I just believe that they connect with people on a deeper level than really any other animal. They’ve been bred to do just that, of course, and for a long time. There is evidence of human-dog cohabitation going back tens of thousands of years. (Cats are a lot more recently domesticated… and it shows.) There are many theories about the co-evolution of humans and dogs, and it has been said (in a generalization whose broadness I wince at, but whose message I endorse) that there have been many great civilizations without the wheel, but no great civilizations without the dog.

So I’ve always been kind of attracted to the idea of dogs in space. The “Mutniks,” as they were dubbed by punny American wags, were a key, distinguishing factor about the Soviet space program. And, Laika aside, a lot of them went up and came back down again, providing actually useful information about how organisms make do while in space, and allowing us to have more than just relentlessly sad stories about them. The kitsch factor is high, of course.

A friend of mine gave me a wonderfully quirky and beautiful little book last holiday season, Soviet Space Dogs, written by Olesya Turkina, published by FUEL Design and Publishing. According to its Amazon.com page, the idea for the book was hatched up by a co-founder of the press, who was apparently an aficionado of Mutnikiana (yes, I just invented that word). He collected a huge mass of odd Soviet (and some non-Soviet) pop culture references to the Soviet space dogs, and they commissioned Turkina, a Senior Research Fellow at the State Russian Museum, to write the text to accompany it. We had this book on our coffee table for several months before I decided to give it a spin, and I really enjoyed it — it’s much more than a lot of pretty pictures, though it is that, in spades, too. The narrative doesn’t completely cohere towards the end, and there are aspects of it that have a “translated from Russian” feel (and it was translated), but if you overlook those, it is both a beautiful and insightful book.

First off, let’s start with the easy question: Why dogs? The American program primarily used apes and monkeys, as they were far better proxies for human physiology than even other mammals. Why didn’t the Soviets? According to one participant in the program, one of the leading scientists had looked into using monkeys, talking with a circus trainer, and found out that monkeys were terribly finicky: the training regimes were harder, they were prone to diseases, they were just harder in general to care for than dogs. “The Americans are welcome to their flying monkeys,” he supposedly said, “we’re more partial to dogs.” And, indeed, when they did use some monkeys later, they found that they were tough — one of them managed to worm his way out of his restraints and disable his telemetric equipment while in flight.

The Soviet dogs were all Moscow strays, picked for their size and their hardiness. The Soviet scientists reasoned that a dog that could survive on the streets was probably inherently tougher than purebred dogs that had only lived a domesticated life. (As the owner of a mutty little rescue dog, I of course am prone to see this as a logical conclusion.)

The Soviet dog program was more extensive than I had realized. Laika was the first in orbit, but she was not the first Soviet dog to be put onto a rocket. Turkina counts at least 29 dogs prior to Laika who were attached to R-1 and R-2 rockets (both direct descendants of the German V-2 rockets), sent up on flights hundreds of miles above the surface of the Earth starting in 1951. An appendix at the back of the book lists some of these dogs and their flights.

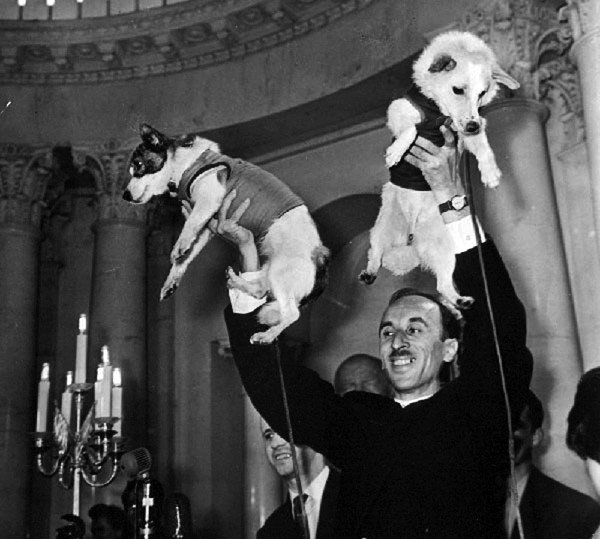

Oleg Gazenko, chief of the dog medical program, with Belka (right) and Strelka (left) at a TASS press conference in 1960. Gazenko called this “the proudest moment of his life.”

Many of them died. Turkina talks of the sorrow and guilt of their handlers, who (naturally) developed close bonds with the animals, and felt personally responsible when something went wrong. Some of the surviving dogs got to live with these handlers when they retired from space service. But when the surviving dogs eventually expired, they would sometimes end up stuffed and in a museum.

I had thought I had heard everything there was to hear about Laika, but I was surprised by how much I learned. Laika wasn’t really meant to be the first dog in space — she was the understudy of another dog who had gotten pregnant just before. Laika’s death was a direct result of political pressures to accelerate the launch before they were ready, in an effort to “Sputnik” the United States once again. The head of the dog medical program, when revealing Laika’s true fate in 2002, remarked that, “Working with animals is a source of suffering to all of us. We treat them like babies who cannot speak. The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it. We shouldn’t have done it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

The Soviets did not initially focus on the identity of Laika. Laika was just listed as an experimental animal in the Sputnik 2 satellite. Rather, it was the Western press, specifically American and British journalists, that got interested in the identity, and fate, of the dog. The Soviet officials appear to have been caught by surprise; I can’t help but wonder if they’d had a little less secrecy, and maybe ran this by a few Americans, they’d have realized that of course the American public and press would end up focusing on the dog. It was only after discussion began in the West that Soviet press releases about Laika came out, giving her a name, a story, a narrative. And a fate: they talked about her as a martyr to science, who would be kept alive for a week before being painlessly euthanized.

In reality, Laika was already dead. They had, too late, realized that their cooling mechanisms were inadequate and she quickly, painfully expired. The fact that Laika was never meant to come back, Turkina argues, shaped the narrative: Laika had to be turned into a saintly hero, a noble and necessary sacrifice. One sees this very clearly in most of the Soviet depictions of Laika — proud, facing the stars, serious.

The next dogs, Belka and Strelka, came back down again. Belka was in fact an experienced veteran of other rocket flights. But it was Strelka’s first mission. Once again, Belka and Strelka were not meant to be the dogs for that mission: an earlier version of the rocket, kept secret at the time, exploded during launch a few weeks earlier, killing the dogs Lisichka and Chaika. These two dogs were apparently beloved by their handlers, and this was a tough blow. The secrecy of the program, of course, pervades the entire story of the Soviet side of the Space Race, and serves as a marked contrast with the much more public-facing US program (the consequences of which are explored in The Right Stuff, among other places).

When Belka and Strelka came back safely, Turkina argues, they became the first real Soviet “pop stars.” Soviet socialism didn’t really allow valorization of individual people other than Stakhanovite-style exhortations. The achievements of one were the achievements of all, which doesn’t really lend itself to pop culture. But dogs were fair game, which is one reason there is so much Soviet-era Mutnikiana to begin with: you could put Laika, Belka, and Strelka on cigarettes, matches, tea pots, commemorative plates, and so on, and nobody would complain. Plus, Belka and Strelka were cute. They could be trotted out at press conferences, on talk shows, and were the subjects of a million adorable pictures and drawings. When Strelka had puppies, they were cheered as evidence that biological reproduction could survive the rigors of space, and were both shown off and given as prized gifts to Soviet officials. So it’s not just that the Soviet space dogs are cool or cute — they’re also responsible for the development of a “safe” popular culture in a repressive society that didn’t really allow for accessible human heroes. Turkina also argues that Belka and Strelka in particular were seen as paradoxically “humanizing” space. By coming back alive, they fed dreams of an interstellar existence for mankind that were particularly powerful in the Soviet context.

Yuri Gagarin reported to have joked: “Am I the first human in space, or the last dog?” It wasn’t such a stretch — the same satellite that Belka and Strelka rode in could be used for human beings, and gave them no more space. A friend of mine, Slava Gerovitch, has written a lot about the Soviet philosophy of space rocket design, and on the low regard the engineers who ran the program had for human passengers and their propensity for messing things up. Gagarin had about as much control over his satellite as Belka and Strelka did over theirs, because neither were trusted to actually fly a satellite. The contrast between the engineering attitudes of the Soviet Vostok and the American Mercury program is evident when you compare their instrument panels. The Mercury pilots were expected to be able to fly, while poor Gagarin was expected to be flown.

Soviet Space Dogs is a pretty interesting read. It’s a hard read for a dog lover. But seeing the Soviet space dogs in the context of the broader Soviet Space Race, and seeing them as more than just “biological cargo,” raises them from kitsch and trivia. There is also just something so emblematic of the space age about the idea of putting dogs into satellites — taking a literally pre-historic human technology, one of the earliest and most successful results of millennia of artificial breeding, and putting it atop a space-faring rocket, the most futuristic technology we had at the time.

There’s a lovely quote from one of the Air Force doctors, Dr Vladimir I. Yazdovskiy about Laika:

Really nice post, Alex…woof.

Khrushchev gave one of Strelka’s puppies to JFK in 1961. When that dog, Pushinka, had puppies Kennedy called them “the pupniks”.

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24837199

Are there still descendants in the U.S.? Bet Alex would like to meet one.

Great article, thanks!

The American idea that an astronaut would actively fly the spacecraft in contrast to the Russian/Soviet idea that the craft would (mostly) fly itself can be seen even in 1930’s science fiction. IIRC Gagarin had a key or password that he could use to take over the controls if needed, however the original plan was that Vostok would fly itself on automatic control. Even today the Progress cargo ships to the Space Station are a good example of how well the Russian automatic technology works.

Also IIRC, American astronauts generally did most of the “flying” on re-entry, rocket ascent went by computer control.

Gerovitch reports that Soviet cosmonauts only had autonomy if something went wrong, so they were prone to conclude that things were “wrong” enough to make adjustments, just so they could feel like they were doing something. On the other hand, it can be argued that the Soviet first of a woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, 1963 — twenty years before Sally Ride) was probably enabled by the fact that they weren’t just focused on macho fighter pilots in the way Americans were.

I show my students the trailer from The Right Stuff (1983) when I teach about the Space Race, as a way of getting a picture of the US space culture, and then contrast that with the secrecy of the Soviet space race. Having your astronauts be heroes before you successfully put them on a rocket has interesting consequences.

I enjoyed your article. Looking at picking up the book. Thanks. Also would like to see a similar article on the chimps in the U.S. program, if you will. Cheers

The most amazing fact I know about Ham, the first US chimp in space, is that originally he was known by his handlers as Chop Chop Chang. Which I like to bring out when lecturing to remind my students that even though these are people who are smart enough to put rockets into space, they aren’t quite advanced enough to not name their experimental animals racist names.

Incidentally, Laika was commemorated not only on postage stamps and matchboxes, but also on the Monument to the Conquerors of Space in Moscow (1964) ( http://www.panoramio.com/photo/45034571 ), along with a punched-tape-wielding computer programmer ( http://www.panoramio.com/photo/45034579 )

And in the Soviet Lunar program, it were a few Russian Tortoises who got to fly above the Moon!

The first Soviet space capsule was so small that only a very small human could fit. Yuri Gagarin was just an inch or two over five feet and was very slender. The Mercury capsule was much larger, able to accommodate astronauts up to 5’11” and 185 pounds.

I like to tell my students that Gagarin got picked because he was the (cue Russian accent) smallest Cosmonaut in all of Soviet Union! Which I think is actually true, though part of the reason he was picked to go first, and Gherman Titov second, was because Titov’s name didn’t sound Russian enough, apparently. Anyway, the joke works well both because it is an amusing thing to know, and because it reminds you that he’s not much bigger than the dog — which ties back to the issue of the Soviets engineers not really considering the human cargo to be all that different from other biological cargo. I like the kinds of jokes that embed deeper historical points in them, because the students remember it for the humor, but retain the historical understanding as well. So I hope, anyway.

If I recall correctly, while the capsule size dictated the height limit for Mercury astronauts, the weight limit was somewhat arbitrary. NASA figured that a man weighing more than 185 pounds might not be in optimal physical condition.

There was a joke at the time that the Russians sent up a man and a dog together. The man was there to feed the dog and the dog was there to prevent the man from touching anything.

There are some interviews with the author on YouTube, findable by googling “советские космические собаки” :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6vCxOqGpq4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JdUCNmcGfTQ

Nick Abadzis made an award-winning comic book (“Laika”) about Laika and the Russian space program at that time. It’s not entirely fact where it strengthens the narrative, but it’s very enjoyable and the artwork is good. It came out a few years ago (Amazon says 2014 but I got it at least 4 years ago) and covers Laika’s real death.

http://www.buzzfeed.com/katienotopoulos/the-kennedys-pets#.sidGYaaYa

Scroll down to the “Pupniks,” and mother.

Fantastic article! As a fellow human companion to a small former street mutt whom I recently discovered is the same size as Laika, this was a real treat.

One note on the automation vs. piloting passage — “poor Gagarin” was, in not flying his spacecraft, glorifying the superior engineering of the Soviet space engineers. The celebration of superior engineering or superior pilots depends on the political context. The differences in piloting (or lack thereof) had lots to do with performing masculinity in either culture, as further evidenced by America’s decision not to send a woman into space immediately following Valentina Tereshkova’s flight in contrast to the rest of the tagging-up of the early-to-mid 1960s.