One of the things I most appreciate about the writers of the show Manhattan is that they took the effort to get beyond the standard, most common vision of the “Los Alamos scientist.” Several of the leading characters are female scientists, good at what they do, good at navigating a profession dominated by men. In the first season, one of the scientists was Chinese-American, and there is also a recurrent character in both the first and second season who is African-American, played with intelligence, dignity, and self-awareness.

Drs. Helen Prins (Katja Herbers), Theodore Sinclair (Corey Allen), and Charlie Isaacs (Ashley Zuckerman) at the Oak Ridge X-10 reactor from Manhattan episode 107.

The textbook version of Los Alamos, and the Manhattan Project as a whole, is a bunch of genius white, male scientists (the Europeans getting the designation of “Jewish” and sometimes another nationality, i.e. “Hungarian”), who have largely been deracinated (not a yarmulke to be seen, not a religious belief to be referenced, except maybe Oppenheimer’s dabbling with Hindu mysticism). Women enter in the picture largely as wives, secretaries, and the operators of Calutrons, ignorant of their true roles. Non-whites are basically eliminated, with the exception of the Indians who served as menial laborers at Los Alamos. This is a view of “who matters” taken largely from the 1940s — it is how the earliest chroniclers of the Manhattan Project saw their world. The one exception to this is Lise Meitner, who was triumphed in the early days of the atomic bomb, largely because of irony in her having had to flee Germany, but also, I suspect, at the irony of her having been a woman.

The historical reality is a much more textured one. There were actually many women contributing to the technical side of the bomb — not just as Calutron operators, either, but as physicists, chemists, biologists, and mathematicians, among other scientific specialities. One of the most overlooked books on the history of the bomb is Ruth H. Howes and Caroline L. Herzenberg’s Their Day in the Sun: Women and the Manhattan Project (Temple University Press, 1999), and it chronicles the lives of many of the women who worked on the project. Along with their stories of individual lives, they also dig into the numbers:

In September 1943, some sixty women worked in the Technical Area at Los Alamos. By October 1944, about 30 percent, or 200 members of the labor force in the Tech Area, the hospital, and the schools were women. Of these, twenty could be described as scientists and fifty as technicians. Fifteen women worked as nurses, twenty-five as teachers, and seventy as secretaries or clerks.

Although many women’s precise job titles at Los Alamos remain unknown, rough numbers show about twenty-five of them working on chemistry and metallurgy, twenty on bomb engineering, sixteen on theoretical physics, four on experimental physics, eight on ordnance, and four on explosives. Two women worked with Enrico Fermi, who had moved to Los Alamos when it opened in 1943. These numbers are given by divisional assignment instead of by job title, so a few of these women may have held clerical jobs, but it’s clear that most of them were scientists or technicians.

The number of women working on the Manhattan Project contrasts sharply with the Apollo Project of the 1960s, which was comparable in size and scope. At its peak in 1965, when Apollo engaged 5.4 percent of the national supply of scientists and engineers, women accounted for only 3 percent of NASA’s scientific and engineering staff.1

The latter part is kind of a kicker for me: more women worked on the bomb than worked on the program to get Americans on the Moon. Why such a disparity? Because during World War II, the need for scientific labor was desperate and spread among many projects. It’s hard to be a bigot when you need every ounce of brainpower and labor you can get, and indeed World War II is famous overall for its movement of women into spaces they had previously been excluded (i.e. Rosie the Riveter). By the late 1950s and mid-1960s, though, the traditional gender norms had been reinstated, and the problem of technical labor shortages had been largely addressed by massive campaigns to increase the numbers of scientists and engineers in the United States.2 As advertisements from the later period suggest, the role of the space-age woman was as the helpful wife — not the person doing the calculations.

A relatively young Katharine (“Kay”) Way, one of the many female scientists of the Manhattan Project, and one of the rare few scientists whose work took her to all of the major Manhattan Project sites. Source: Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

There are a lot of interesting lives there, generally ignored when we tell these stories. Katharine Way is one of my favorites. She had a PhD in nuclear physics from University of North Carolina, having been John Wheeler’s first graduate student. She worked on neutron sources at the University of Tennessee early in the war, and, hearing rumors of a big project at Chicago, called up Wheeler and talked her way into the Metallurgical Laboratory. There she worked on many topics key to the operation of reactors: neutron fluxes, “poisoning” by fission products, reactor constants, and eventually the Way-Wigner formula for fission-product decay. Her work was important enough for her to warrant visits to Hanford, Oak Ridge, and Los Alamos — a remarkable feat given the high levels of compartmentalization (many of the scientists who worked at any one of the sites were not allowed to know where the other ones were located). Even before Hiroshima, she questioned the morality of the weapon she had helped produce (signing Szilard’s petition against its use), and in the postwar she was a key player in the postwar Scientists’ Movement, co-editing One World or None with Dexter Masters in 1946.3

The Manhattan character Helen Prins, played by Katja Herbers, reminds me of Way, in terms of the arc of her narrative: her gumption (imagine talking yourself onto the Manhattan Project!); the way in which, despite being relatively low in the hierarchy, her work touches on enough key problems that it leads her all over the place (which works well for a plot, but it somewhat true to life as well), and the way in which she, like many others who worked enthusiastically during the war, came to doubts about the uses to which their science had been put.

Chien-Shiung Wu at the Smith College Laboratory in the 1940s, shortly before joining the Manhattan Project. She is working on an electro-static (Van De Graaff) generator. Source: Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

There were also minorities on the project in technical roles, though here the lack of equal opportunity is far more stark and evident. Chien-Shiung Wu, a Chinese-born physicist, completed her dissertation in physics under Ernest Lawrence at UC Berkeley in 1940. After receiving a phone call from none other than Enrico Fermi, she was the one who identified Xenon-135 as a fission-product that was causing the Hanford reactors to lose their reactivity over time (this is the so-called “poisoning” effect). She also worked with Harold Urey on the problem of gaseous diffusion while at Columbia University, among other things. She would later become the first female president of the American Physical Society, in 1975.4

The Manhattan Project had very large numbers of African-Americans, but they were mostly working at Oak Ridge and Hanford as laborers or janitors. Peter Hales’ Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (University of Illinois Press, 1999) has a thoroughly interesting chapter on the “Others” of the bomb work, including African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Native Americans, and women. Oak Ridge was rigidly segregated during the war, with crude “Negro hutments” that held five men or six women in a single room (white hutments were similarly crude, but only had four occupants). The history of segregation at Oak Ridge is quite interesting — Groves apparently issued orders for a “separate but equal” set of accommodations, but his subordinates instead clearly saw the goal as creating a “Negro shantytown.” Hanford housing was also segregated, but accommodations were generally better, although in many ways the African-American laborers received fewer perks than the white ones (for example, in terms of recreational facilities built for them). These differences among sites were largely the difference of one being in located in Jim Crow Tennessee and the other in Washington State.5

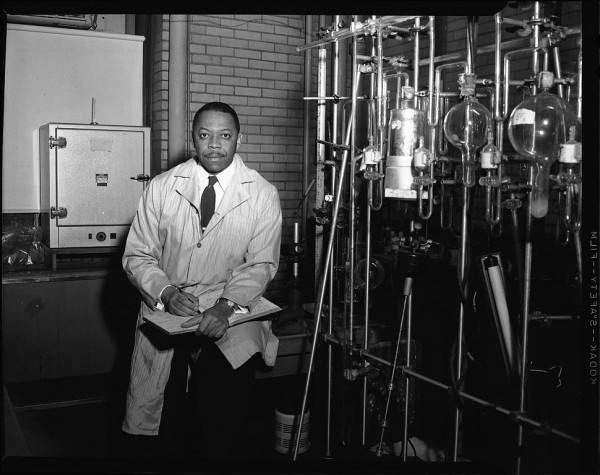

Met Lab chemist Moddy Taylor — not the “typical” image of a Manhattan Project scientist. Photo from 1960. Source: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History.

There were a few African-American scientists on the Manhattan Project. Samuel P. Massie, Jr., worked at Iowa State University on uranium chemistry for use in enrichment work. Jasper Jeffries worked as a physicist at the Metallurgical Laboratory, and was one of the signatories of Leo Szilard’s petition to not use the bomb on a city without warning. Benjamin Franklin Scott worked as a chemist at the Met Lab in their instrumentation and measurements section. Moddie Taylor also did chemistry at the Met Lab, analyzing rare-earth metals. There are several others — the American Institute of Physics has a nice compilation of biographies on their website — mostly centered around the University of Chicago. With any kind of “omitted” history of this sort, one wants to honor them without overstating their importance or underestimating the effects of institutionalized exclusion.6

As a side-note, I was asked by a reporter last summer whether there were any known cases of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered (LGBT) on the Manhattan Project. This is a tricky thing to answer. There were some half a million people working on the bomb across all of its many sites — some number of them had to be LGBT based on whatever prevalence one thinks existed in the population at that time. Even if it was only 1% (which is very conservative), that would allow for 5,000 individuals across the entire project. The populations of present-day US states range from around 2% to over 5% in self-identification as LGBT, so that is quite a lot more people (especially if we acknowledge that even at our current point in time, there are certainly many people in the closet or in a state of self-denial). Of course, in the 1940s homosexuality was categorized as a psychiatric disorder and by the late 1940s it was considered a serious security risk (the “Lavender scare”). To be public about such a thing would not be conducive to working on top-secret war work, to say the least — so there had to have been quite a lot of people who were in the closet.

Alumni of the creation of the first nuclear reactor, CP-1, at the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory. Leona Woods Marshall is conspicuously outside the norm, but part of the crew nonetheless. Source: Emilio Segrè Visual Archive.

The issue of women and minorities in STEM fields is still a real one. For those who smugly believe that large portions of the population simply don’t have the ability to contribute on technical matters, I have found Neil deGrasse Tyson’s discussions of his own difficulties as an African-American interested in astrophysics to be a useful reference. In the case of the Manhattan Project, there are interesting trends. At times things were more open on the bomb work, for women in particular, because they could not afford to write off brainpower of a certain type. For issues of labor, however, the local cultures — New Mexico, Washington, and Tennessee — all came through largely as you would expect them to.

The initial stories about the making of the bomb, however, largely wrote out all non-male, non-whites from the story. Partially this was a real recapitulation of the the hierarchy in place: there were women and there were minorities, but they didn’t generally get to run things, and the story of making the bomb was often about who was running things. But partially this was about the biases of the time, and what was considered acceptable from the perspective of the storytellers (and, arguably, society itself — imagine if a woman or minority had tried to get away with Feynman’s hijinks, whether they would be treated as amusing or not). There has been a lot of good work expanding our understanding of who made the bomb in the last 15 years, though it has not quite unseated the popular vision of a handful of brainy white men creating a weapon out of sheer cleverness and equations alone.

- Emphasis added. Ruth H. Howes and Caroline L. Herzenberg, Their Day in the Sun: Women and the Manhattan Project (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 13-14. [↩]

- On the latter, see the work of David Kaiser on the booms and busts in the sciences from Sputnik onward. [↩]

- Howes and Hertzenberg, 42-43. [↩]

- Howes and Hertzenberg, 45-46. [↩]

- Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), chapter 7. [↩]

- There is a very nice paper online about African-American scientists and the atomic bomb: Shane Landrum, “‘In Los Alamos, I feel like I’m a real citizen’: Black atomic scientists, education, and citizenship, 1945-1960,” (Brandeis University, 2005). There is a bit of literature on African-American responses to the bomb, as well: see, e.g., Abby Kinchy, “African Americans in the Atomic Age: Postwar Perspectives on Race and the Bomb, 1945–1967,” Technology and Culture 50, no. 2 (2009), 291-315. [↩]

Based on stories I’ve heard over the last 40 years, I was convinced that the married couple who, in the first episode of “Manhattan,” have the pointed and funny exchange with the vendor about starting a garden at Los Alamos, was based on my in-laws.

Here’s a recent Providence Journal piece about my MIL, who had a fairly central role.

http://www.providencejournal.com/article/20150809/NEWS/150809334

Many, many more white laborers lived in “hutments” than African Americans in Oak Ridge. Separate but equal was the law of the land at the time, not a Groves directive and was the general rule followed by the armed forces.

I don’t know about the exact numbers (I have not seen any), but my understanding is that there were major differences in white and African-American housing at Oak Ridge. Aside from the fact that they put more African-Americans in each hutment, there were no operations jobs at Oak Ridge for African-Americans that were not it hutments. This was not the case for whites, who could also live in houses and barracks. Whites with families could get houses; African-Americans with families were separated and treated as single individuals. The “Colored Hutments” were also kept (in violation of safety recommendations) directly next to industrial areas. Percentage-wise, far more African-Americans had hutments than whites.

Your information is not accurate Alex. The “colored” hutments were in very close proximity to the white housing- albeit separate (as required by the law at that time) and separated by the same ridge and valley from “industrial areas” as the white sections- if an accident had happened blacks and whites would have been more-or-less equally effected. There was less than a couple of hundred yards separating some whites from blacks, but in a city as spread out as Oak Ridge was (7 miles X 19 miles) obviously some were separated by a substantial distance. There were thousands of white workers living in hutments in Oak Ridge and the housing was identical within the same job classifications, i.e., laborers vs laborers. The population of African Americans was very small even at the peak of construction. Houses were not readily available to anyone other than those people rated as priority workers which included scientists, highly skilled technical workers, and site “management” which included some military personnel and there was a “waiting” list right up until the end of the war.

The information I have comes from Hales’ Atomic Spaces, which goes into some considerable detail about the housing options. I have not seen any information with detailed information about the breakdowns of population by numbers, but the Manhattan District History says there were at least 450 hutments in the “colored” area, as contrasted with around 800 white hutments.

Your estimate that 1 percent or more of the people working on the Manhattan Project could probably be regarded as LGBT leads me to wonder whether any characters on Manhattan, either on the project or not, can be seen in those terms. Given that this, unlike such obvious attributes as being female or nonwhite, may figure into plot developments, are you at liberty to say? The only episode I’ve seen so far included something that prompted the question; I won’t be more specific.

Incidentally, your reports on the show and its background have done much to pique my interest in it. I hope its creators are happy with your work.

There was an LGBT sub-plot in the first season, which is why I was asked this question by the reporter. I don’t know if there are future developments along these lines — I have not seen the scripts to all of the episodes. I am aware of many of the “elements” of the scripts (I was extremely pleased for a patent lawyer to show up in the latest episode, for example), but I don’t always know how they are going to integrate into the plot until I see it on the screen. It makes for an interesting viewing experience (and perhaps an annoying one for my wife, because I’m always nudging her and saying, “I helped them with that!” while we are watching).

I suppose Luis Alvarez would have been the highest ranking minority on the Manhattan Project.

While there may not have been any openly gay people of note working on the MP, one of the top government officials at the time, House Speaker Sam Rayburn, was a closeted gay man.

Alvarez is a tricky person to categorize — his father was Spanish (European), his mother white (her father was Irish and her mother American, though she was born in China). In his appearance and upbringing, I think he would be categorized as “white,” but this is one of those tricky areas where culture and ideas about race get into problematic places. His father and he are identified as “white” in the 1920 census, for whatever that is worth (the only standardized options were “White,” “Negro,” “Indian,” “Chinese,” “Japanese,” “Filipino,” “Hindu,” and “Korean”).

[…] a non-women-specialist blog in this week’s new post at Restricted Data: The Nuclear Secrecy Blog, Women, Minorities and the Manhattan Project. These historians are showing the way. Let’s get away from emphasising the same small handful of […]