This ended up being part one of a three part arc: Part I (in which I introduce the question), Part III (in which I talk about some “new” discoveries)

It’s been a busy month; aside from “regular work” sorts of duties (teaching, grading, writing, e-mailing, programming, book reviews, grant proposals, oh my!), I’ve been sucked into various discussions relating to presidential command and control after my last post, which got me a solicitation to write an op-ed for the Washington Post on presidential authority to launch nuclear weapons. I haven’t really gotten around to screening all the comments to my blog post, and Post piece has 1,200 comments that I’m just not going to bother trying to wade into. I thought though that I would post a few quick responses here to common comments I’ve gotten on both pieces.

The print version of my Post article (December 4, 2016). Thanks to my DC friends for sending me print copies — apparently one cannot buy the Post anywhere in Hoboken. You can read the online version here.

Both pieces are about the history and policy of presidential authorization to use nuclear weapons. In a nutshell, in the United States the President and only the President is the ultimate source of authority on the use of nukes. This is entirely uncontroversial, and the articles describe the history behind the situation.

The trickier questions come up when you ask, can anyone stop nuclear weapons from being used if the president wants to use them? Everything I’ve been able to find suggests that the answer is no, but there are ambiguities that various people interpret differently. For example, there are two separate questions hidden in that first one: can anyone legally stop the president, and can anyone practically stop the president? I will get into these below.

The most curious response that I’ve heard, both in person and second-hand, are people who have heard what I’ve said about this, and say, “that can’t be true, that would be a dumb/crazy way to set things up.” This is often a purely emotional response, not one based on any research or specialized knowledge — a pure belief that the US would have a “smarter” system in place. I find it interesting because it is a curious way to just reject the whole topic, some sort of mental defense mechanism. Again, everything I’ve found suggests that this is how the system is set up, and in both the blog post and the Post article I’ve tried to outline the history of how it got to be this way, which I think makes it more understandable, even if it’s still (arguably) not a great idea.

And, of course, because it featured the name “Trump,” a somewhat hyperbolic headline (which I didn’t write, but don’t really hate — it elides some caveats and ambiguities, but it’s a headline, not the article), and is in the Washington Post, there were a lot of people who wondered whether this was just a partisan attack. And amusingly had a number of people accuse me of being a Post employee, which I am decidedly not. My writing has also been sometimes referred to as “hysterical,” which is an interesting form of projection; to my eye, anyway, it is intentionally pretty sober, but I suppose we see what we expect to see, to some degree.

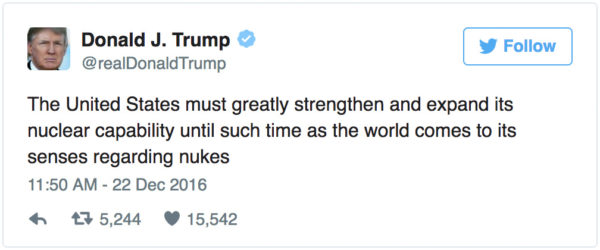

Interpreting a Trump tweet is no easy matter, and serves as sort of a political Rorschach test. The above is either completely in line with Obama’s nuclear modernization plan, or a call for something entirely different. I guess we’ll see…

It’s true that I think this issue is particularly acute with regards to Mr. Trump; if nuclear war powers are vested in the person of the executive, then the personality of the executive is thus extremely important. And I think even his supporters would agree that he has a reactive, volatile, unpredictable personality. He broadcasts his thin-skinnedness to the world on a daily basis. And a president who complains on a weekly basis on his portrayal on Saturday Night Live is, let’s be straight, thin-skinned. To be offended by comedic parody is beneath the station of the job, something that any American president had better get beyond.

But frankly I would be just as happy to have been talking about this in a Clinton administration, and would have been happy to talk about it during the Obama administration. The issue, and my position, still stands: I think that vesting such power in one human being, any human being, is asking a lot. And this has nothing to do with how reliable they seem at election-time: we have historical instances of presidents who had health problems (Wilson), were heavy users of painkillers (Kennedy) or alcohol (Nixon), or who were later discovered to be in the early stages of mental decline (Reagan). There is no reason to suspect that the president you elect one year will continue to be that person two or three years later, or that they will be totally reasonable at all times. And I don’t think anyone of any political party in the USA would go out on a limb to suggest that the US electorate will always elect someone whose can bear all that responsibility. So this doesn’t have to be, and shouldn’t be, a partisan issue, even if Trump in particular is getting a lot of people to start talking about it again.

One of the responses I’ve heard is that no further “checks” on presidential nuclear command authority are needed because any president who wanted to use nuclear weapons unilaterally, against the judgment of their advisors, would be agreed-upon as “insane” and thus could be removed from office under Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment of the US Constitution. This is, I think, not adequate.

For one thing, the procedures are understandably complex and require a lot of people to participate — it is appropriately difficult for a president to be declared “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office,” because if it were easy, that would be an easy way to dispose of an unpopular president. So it is not the sort of thing that can be made to go into immediate effect with quick turn-around, which really does not help us much in the nuclear situation, I don’t think.

Secondly, while the “insane president” idea often dominates the discussion here, that is an extreme and not entirely likely case. I am much more worried about the “president with bad ideas” approach, possibly a “president with bad ideas supported by a few advisors” approach. There are many nuclear-use scenarios that do not involve an attempted preemptive attack against Russia, for example. Not all will be “obviously insane.” And even a president who advocated first-use would not necessarily be “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office” according to the people who need to agree to such a statement. This is a cumbersome, high-stakes approach; if the only way to stop a president from doing dumb things with nuclear weapons is to kick them out of office on the basis of them being medically unfit, that is a very difficult bar to climb to. (And we can add impeachment under the same objection — that is not a fast nor straightforward process, nor is it any kind of obvious deterrent to the kind of president who might consider using nuclear weapons in the first place.)

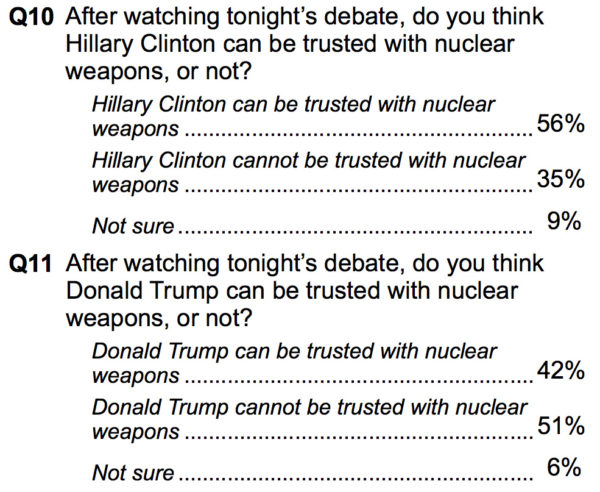

Results of a poll taken after the first presidential debate, on whether the candidates could be trusted with nuclear weapons. There are many ways to read this, but I think at a minimum we can say that when substantial percentages (much less a slim majority for one of them) of Americans believe that neither major-party nominee can be trusted with nuclear weapons responsibility alone, it’s time to rethink whether we should have a system that invests that decision completely in the president.

Another objection I’ve gotten is the “maybe there are checks that you just don’t know about, because they’re classified.” Fair enough, and I acknowledged this in my writings. Much about the procedures involved are classified, and there are good reasons for that. If an enemy knew exactly how the system worked, they could potentially plot to exploit loopholes in it. But I have two main responses on this.

First, if complete knowledge in the nuclear realm was necessary to talk about nuclear policy, then literally nobody could or would talk about it. Which means democratic deliberation would be impossible. So those of us without clearances can, and should, talk about what we do and don’t know, openly on both fronts. I try to make very explicit where my knowledge begins and ends. I would be completely thrilled if these discussions led to official clarifications — I think these issues are worth it, and if my understanding is wrong, that would be great.

Second, it strikes me as an act of tremendous optimism to assume that things in the US government are more rationally run than all signs indicate they appear to be. The study of nuclear history is not a study of unerring rationality, of clear procedures, or of systems set up to guarantee wise decision-making. It is easy to document that our command and control systems have been optimized towards three ends: 1. preventing anyone but the president from using nuclear weapons in an unauthorized fashion, 2. reliability of response to threats and attack, and 3. immense speed in translating orders to action. None of that suggests we should assume there are elaborate checks and balances in the system. My view: unless positive evidence exists that a government system is sufficiently rational, to assume it is sufficiently rational requires tremendous faith in government.

Lastly, to get at the strongest of the responses: the president is the only person who can order nuclear weapons to be used, but doesn’t the execution of that order require assent from other people to actually get translated into action? In other words, if the president has to transmit the order to the Secretary of Defense (as some, but not all, descriptions of the process say has to occur), and the Secretary of Defense then has to transmit it to the military, and the military has to transmit it into operational orders for soldiers… aren’t there many places in that chain where someone can say, “hey, this is a terrible idea!” and not transmit the order further?

In thinking about this, I think we have to make a distinction between a legal and a practical hinderance. A legal hindrance would be the possibility of someone being able to say, legally and constitutionally, “I refuse to follow this order,” and that would stop the chain of command. This is mentioned in the 1970s literature on presidential authority as a form of “veto” power. It is not at all clear that this is legally allowable in the area of nuclear weapons — it is, to be sure, an ambiguous issue of constitutional, military, and international law. I have seen people assert that the use of nuclear weapons would be unquestionably a war crime, and so any officer who was given such an order would recognize it as an illegal order, and thus refuse to obey it. I don’t think the US government, or the US military, sees (American) use of nuclear weapons as a war crime (a topic for another post, perhaps), and whether you and I do or not matters not at all.

And from a practical standpoint, we know the system is set up so that the people at the very bottom, the people “turning the keys” and actually launching the missiles, are trained to not question (or even deeply contemplate) the orders that reach them. They are trained, rather explicitly, that if the order comes in, their job is to execute it — not quite like robots, but close-enough to that. The speed and reliability of the system requires these people to do so, and they are not in a position to inquire about the “big picture” behind the order (and would not presume to be qualified to evaluate that). So if we take that for granted, we might ask ourselves, at what level in the hierarchy would people be asking about that? One can imagine a lot of different possibilities, ranging from a continuum of second-guessing that was fairly evenly gradated towards the “top,” or one that was really “band-limited” to the absolute top (e.g., once the order gets made by the president, it is followed through on without questioning).

I suspect that even the military is not 100% sure of the answer to that question, but I suspect that the situation is much more like the latter than the former. Primarily because, again, the US military culture, especially regarding nuclear weapons, is about deference to the authority of the Commander in Chief. Once you get beyond a certain “circle” of people who are close to the president, like the Secretary of Defense, I would be very surprised if the people in the nuclear system in particular would buck the order. The system and its culture was built during the cold war, focused on rapid translation between order and execution. Until I see evidence that suggests it has radically transformed itself since then, I am going to assume it acts in that way still. And again, everything I have seen suggests that this is still the case. As former CIA and NSA head Michael Hayden put it before the election: “It’s scenario dependent, but the system is designed for speed and decisiveness. It’s not designed to debate the decision.”

OK, but in practice, couldn’t the Secretary of Defense just refuse to act? Here it really becomes necessary to know how the system is set up, and I just don’t think enough information is out there to be definitive. From what I understand, the main role of the Secretary of Defense is to authenticate the order — to say, “yes, the president made this order.” Are there ways to get around that requirement, or around a stubborn Secretary of Defense? A practical one would be to just fire him on the spot, in which case the requirement for authentication moves down a notch in the Department of Defense succession rank. It could go onward and onward down the line, I suppose. But more practically, I have heard it suggested (from people who study such things) that there are protocols by which the president could bypass the Secretary of Defense altogether and communicate directly with the National Military Command Center to communicate such an order. I am still looking into what we can say about such things with conviction, but it would not surprise me if there were contingencies in place that allowed a president a more direct means of sending such orders, as part of the goal of making the system especially resilient in times of crisis (when appropriate representatives from the Department of Defense may not be available).

There is a famous anecdote about Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger requesting that all nuclear commands from Nixon in the final days of the administration be routed through him. It is not clear that it is true, and may be exaggerated greatly, but it is often cited as a means that a Secretary of Defense could override presidential authority. Even if it were true, it is ad hoc, probably illegal, and a pretty thin “check” to rest one’s hopes upon. And I would suggest that about any assertion that “practical” constraints exist in the form of individuals refusing to follow orders — they’re highly optimistic. Especially since there is a lot of options other than a raving president shouting “nuke them all!,” which would be pretty easy to disobey. There are many more scenarios that do not involve obvious insanity, but could still be terrible ideas.

In my Post piece, I discussed possible resolutions. None could be completely satisfying; the nuclear age is defined by that lack of total certainty about outcomes. But there have been proposals about requiring positive assent from more people than just the president for any kind of first-use of nuclear weapons. I discuss the Federation of American Scientists’ proposal in my Post piece, and the fact that you could use that as a template for thinking about other kinds of proposals. I am not wed to the idea of getting Congressional approval, for example. Frankly I’d be happier if there were a legal requirement that would codify the Secretary of Defense’s veto power, for example. One can productively debate various options (and I’m still thinking about these questions), and their legality (it is a tricky question), but I still think it would be a valuable thing to give people at the highest levels something non-ad hoc to fall back upon if they wanted to actively refuse to obey such an order. The common objection I’ve heard to such an idea is, “maybe we don’t need it, there might be hidden checks in place,” which is not much of an objection (relying on optimism in the system).

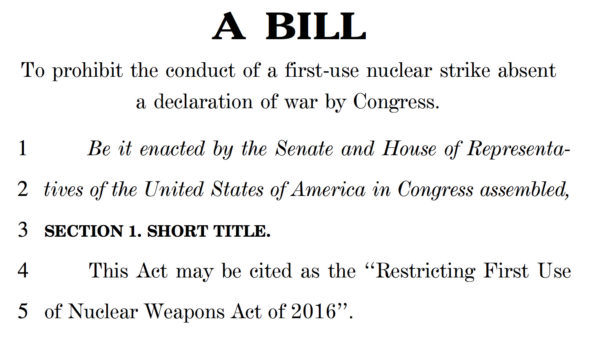

Congressmen Ted Lieu (D-CA) and Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) introduced a bill last September that would require a Congressional declaration of war before first-use of nuclear weapons would be allowed. I don’t think that’s necessarily the right approach (Congress has not issued a declaration of war since World War II, so this is effectively just a prohibition on first-strike capability, which will lead the military, defense establishment, and most security scholars I know to definitively oppose the idea), but I hope that this might serve as a place to revisit and discuss these issues formally in a legislative setting. I am not convinced I have the perfect policy solution, but for me an idealized law would have provisions that allowed for first-use in emergency circumstances, with at least one other human being (preferably more, though not an impractical number) having to actively agree with the order (and having veto power over it). I think this is a rather modest suggestion. It would not completely rule out first-strike possibilities — nothing would, save lack of nuclear capability altogether, and that’s a separate can of worms — but it would allow the American people, military, and political establishment to know that no single human being would be shouldering that responsibility alone.

Alex,

Great expansion of the original article. A few thoughts:

I think your suggestion in the very last paragraph makes a lot of sense both militarily and politically as a first strike is very much in both realms. What came to mind was the composition of the team in “The Andromeda Strain” that required at least one team member to be single using the logic that he or she would be less likely to hesitate about blowing up the complex due to human/family considerations.

For a strategic first strike I would have a four person team consisting of the President, SecDef (to represent the military), the House MINORITY Leader (to represent the political side and to ensure that both sides of the political aisle have input; House, not Senate, because they are constantly on the pulse of their constituency because they are essentially always running for office every 2 years) and finally, a private citizen who is unmarried (I have no idea how you would choose that person). It would take agreement by a majority to strike but you only need three of the four to have a quorum. I know that is unwieldy but that might be a good thing for a strategic first strike decision. For a retaliatory strategic or tactical first strike nuke scenario just the President is fine. That needs to happen almost immediately. If the President delegates the tactical first strike authority to a Combatant Command Commander then that is his prerogative.

Finally, I’ll add my relatively small personal nuke experience. I was a US Army officer in a Border Cavalry unit in Germany for the last three years of the Cold War. Since my battle positions in OPLAN 33001 (how to fight WWIII) were literally right on the East German border I had tactical nukes available to call for if certain conditions were met on the ground (mostly if we were going to be immediately overrun and destroyed). I never knew where they were deployed or who owned them, we just knew they were available. I gave no small thought to the question: If those conditions were met would I call for them? The reality was that if those conditions WERE met my soldiers and I would most likely not survive what was coming. My fellow officers and I discussed this and we all agreed that if we did request them and they were fired it could lead to nuclear Armageddon and no one on earth would survive. But we also agreed if those conditions were met we would call for them. That was the way the system was designed and we were going to use the system as designed. I forget how long we were told it would get for our request to go through the tactical fire control center to NATO to the President and then back to the firing battery but it was going to be at least a few minutes and in that combat scenario, a few minutes was all we had for the strike to be effective so that we could exploit its effects on the enemy. So for the tactical scenario, if it still exists, it doesn’t have time for getting 3 or 4 people involved in a philosophical discussion. The decision matrix needs to already have accounted for that a priori.

Despite the conceivable problems with the current system, putting the launch decision in the hands of one person has the virtue of being relatively simple. The desire to put someone else in the loop is understandable but faces two questions. How would this system work in practice to prevent unilateral action by the president in the “normal” situation, in which no nuclear weapons have been used by an adversary, and how does it get out of the way once a nuclear attack is known or believed to have begun?

The quotation from Michael Hayden—“the system is designed for speed and effectiveness”—makes an important point but omits the reason. An ICBM launched from afar doesn’t take particularly long to reach the continental United States, and an SLBM launched from somewhere just off the Atlantic or Pacific coast or in the Gulf of Mexico would take even less time—a matter of minutes, I believe, but I don’t have the numbers at hand. If we place a lock on the football—regardless of whether it calls on a congressional committee, the Secretary of Defense, or some other means—it will have to be easy to remove in such a situation.

I agree. If I were making a model act, it might look something like this: Before a US first-strike with nuclear weapons could occur, the President would have to get the positive assent of X, where X is some other group of people. (Exploring who would be a good X is a separate question in my mind.) To do otherwise would be an illegal act, unless the president would certify that he believed it was a launch-under-attack situation (there are inbound nukes), or some equivalently existential situation. One could play with that definition a bit, to make it clearer, but the gist would be that it had to be a threat on the order of a nuclear weapon going off imminently.

Would that be an absolute prohibition? No. But it would make crystal clear the legality, both to the president and to whomever moved the action forward. It would still allow, for example, a preemptive strike of sorts against a nuclear power that had not yet launched their missiles. But I think the bar for unilateral use should not be much lower. Anything lower should require consultation, deliberation, and N+1 consent of some sort, I feel.

Would this totally remove the possibility of no-first-use? No. It is not a no-first-use pact in any way. Would it totally remove the possibility of a rogue, lying, deceitful president misusing the system? No. But I think it would work to deter such a thing to some degree.

In the event of a nuclear attack, it will not be the President who wakes up with a bad dream and orders up a pre-emptive “retaliatory” attack. Rather, it will be the national command authority, awake and sober, monitoring a variety of satellite signals, radar, and whatever else, who wakes up the President. In the latter event, there is already the verified circumstance that could unlock the President’s football, requiring no further validation or seconding of the President’s orders.

This type of message from the national command authority is a rare event. It has only happened once in Russia (1995) and never in the U.S. (but has “almost” happened at least once in the U.S.). While too rare to assign an exact probability, these mistaken messages for a President to decide upon have come about once every fifty years.

Assuming we continue a policy (or ambiguity) that allows launch of nuclear weapons on mere warning of a missile attack, there would be no interference with the hurried-up launch of nuclear weapons under this type of circumstance. Of course, both Congress and the President have the option to discontinue this risky policy (or ambiguity) of launch on warning by making it illegal.

—This is a cautious statement. I was under the impression that the *idea* of a foreign spy sneaking a nuclear weapon into the United States has been around for decades. The my question being: is it assumed that before an attack on the US was launched by enemy planes and missiles, an enemy nuke would wipe out the president, one hidden near his location?

—This “decapitation” idea must have been discussed, at least by intelligence agencies. I assume it is far fetched. But it would cut the Presidents response time from minutes to zero seconds.

There are, built into the system, well-defined succession procedures. I don’t know how those work in practice (whose authentication is allowed, when certifying that some number of people have died?), but the system is to some degree flexible with respect to whether the president or others are still alive or not.

You seem to be starting from the assumption that a no first use (NFU) policy is undesirable and the system should be set up to make first use difficult but not impossible. I disagree that this is the right approach for the United States. I believe any country’s nuclear use policy should start from the assumption that these weapons are meant to fill in the serious gaps in its defense policy that it cannot fill with its conventional arsenal.

Throughout the Cold War, the US and its European allies faced a crushing inferiority in conventional weapons vis-à-vis the Warsaw Pact. Had war erupted, the Soviets and their allies could have reached the North Sea and the Rhine and, had France not stayed neutral, the Channel and the Pyrenees. It made no sense fo the United States (or Britain or France, for that matter) to declare an NFU policy under these circumstances, for it would have served as nothing more than an invitation to attack; and it made perfect sense to loudly signal its willingness to use nuclear weapons in wartime regardless of the other side’s behavior.

Israel would be faced with the prospect of annihilation if it had to face the combined forces of all the other Middle Eastern powers (an admittedly unlikely scenario). So, putting aside for a moment its policy of nuclear ambiguity, it makes no sense for Israel to declare an NFU policy.

Pakistan, if it had to fight a war with India without the backing of China, would, because of its geography, risk being split in 2 by a strong Indian push towards the Afghan border (such as along the Islamabad-Peshawar axis) – hence its historical obsession with controlling Afghanistan. So it makes sense for Pakistan not to declare an NFU either.

But the United States today is a country that is not in danger of facing a crushing conventional defeat from any of its adversaries. The situation in Europe is significantly more favorable than it was during the Cold War – the potential frontline is no longer through the center of Germany but in former Soviet territory. (You can see the Russians reacting to this shift – Putin is doing everything he can to convince the world he has his finger on the button, the sort of saber-rattling that Soviet leaders would never have engaged in.) North Korea, for all the men it has under arms, could not defeat South Korea even in a one-on-one matchup. And initial defeats at the hands of China and Iran are something the US could bounce back from.

In none of these potential conflicts would first use of nuclear weapons be a necessity. An explicit NFU policy is something that the United States government can afford in practice, would benefit from in terms of its international standing and would serve to signal to nuclear-armed adversaries to avoid turning a conventional war into a nuclear one on the assumption that the US is about to do it. If anything, a disguised NFU policy is an unnecessary half-measure – it surrenders the PR benefits of an explicit policy and muddies the message being sent to adversaries.

To summarize, since the United States military enjoys a comfortable superiority over its likely enemies, the United States government can very much afford the luxury of an NFU policy.

This does not, of course, preclude the possibility that the situation may at some point once again become dire in ways that require the US to wield the threat of first use. For instance, while war with Russia, China or Iran can be won (or rather not lost) with conventional weapons only, war with all 3 (or maybe even a combination of 2 of them) may require sacrificing an NFU policy. But such situations do not develop overnight – they come with warnings. And no policy should be seen as an unconditional, open-ended commitment.

What I have in mind right now is a combination of the Lieu-Markey bill and an explicit NFU policy on the part of the executive. So on the one hand, Congress would pass, and the president would sign into law, a bill requiring congressional approval for the launch of a nuclear strike (declaration of war or not) against a country that has not and is not about to launch its own nuclear strike on the United States. And on the other hand, the president would not only accept this limit on his/her power, but would also declare that no approval is likely to be demanded of Congress because, barring extreme or unforeseen circumstances, (s)he has no intention of ever launching such a strike.

I just think these are segregable issues. The defense and strategic community vehemently resist a blanket no-first-use policy. One can debate the merits of it, and I can see both sides of the argument. I’d prefer to step around that argument at this point, on this issue. We can have sensible limitations on first-use without deciding whether we need it to be an absolutely no-first-use. If one thought no-first-use is a good idea, this is a sane step in that direction. If one thinks no-first-use is a bad idea, this doesn’t preclude it, it just makes it more deliberative. I suspect any policy that Congress would have a chance of adopting would need to be similarly moderate. But I am not a policymaker…

Sure. But I think the political reality is such that even sensible limitations and a sane step in that direction are unlikely. If the discussion is about what *might* happen, it’s a brief one: sadly, probably nothing. If the discussion is about what *should* happen (short of universal nuclear disarmament), well, obviously nobody has to agree with me, but I think a strong case can be made for a full NFU policy (call it 99% NFU, because there’s always an unforeseeable or extreme 1% that can overturn any policy).

But then, the reason nothing is likely to happen is that this issue isn’t really in the public sphere. Nuclear weapons policy isn’t really something Americans have spent a lot of time thinking about since the Cold War ended and there’s a lot of misinformation and just plain ignorance. I think you can tell as much from the responses you got. Pushing for a full NFU policy is how you might end up with a partial NFU policy as a compromise.

People have pushed for full NFU policies for decades; they didn’t get traction under Obama, the president who was perhaps most amenable for the idea. Whereas there actually is a proposal for increasing consultation prior to first use on the books in Congress.

I would say it is worth trying something new, something that you could actually presumably get bipartisan Congressional support for — because as I’ve noted elsewhere, this is about Congress reasserting its relevancy (to some degree) in nuclear use decisions, not about changing fundamental strategic positions, which a NFU policy would be.

Getting bogged down in the same old, same old NFU debates will not, I don’t think, get us anywhere new. Whereas a discussion about presidential authority might, because this president raises those issues quite broadly with his temperament.

A real NFU policy has plenty of strategic objections to it. Something that removes unilateral presidential authority under most conditions, however, does not run into those issues to quite the same degree.

I think NFU is a political dead-end in the United States (at least in the short term), whether or not it is a good idea (which, again, is debatable).