As we approach the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, even with everything else going on this year, we’re certainly going to see an up-tick in atomic bomb-related historical content in the news. As arbitrary as 5/10 year anniversaries are, they can be a useful opportunity to reengage the public on historical topics, and the atomic bombs are, I think, pretty important historical topics: not just because they are interesting and influential to what came later, but because Americans in particular use the atomic bombings as a short-hand for thinking about vitally important present-day issues like the ends justifying the means, who the appropriate targets of war are, and the use of force in general. Unfortunately, quite a lot of what Americans think they know about the atomic bombs is dramatically out of alignment with how historians understand them, and this shapes their takes on these present-day issues as well.

The beginnings of the Hiroshima anniversary night lantern ceremony, 2017, which I attended.

Having seen the same recycled stories again and again (and again, and again), I thought it might be worth compiling a little list of what journalists writing stories about the atomic bombings ought to know. This isn’t an extensive debunking-misconceptions list (I’ll probably write another one of those another time), or a pushing-a-particular perspective list, so much as an attempt to talk about the broader framework of thinking about the bombings, so far as scholarship has advanced past where it was in the 1990s, which was the last time that the broader popular narratives about the atomic bombings were “updated.”

I’m tilting this towards journalists — particularly journalists trying to represent this from an American perspective, so frequently (but exclusively) American journalists — not because they get it particularly wrong (they often do get it wrong, but so do even academics who don’t study this topic in detail), but because they are usually the primary conduit of this history to the broader public. And because, in my experience, most journalists who want to write on this topic are not bungling it because they are trying to push an agenda (that occasionally does happen, to be sure), but because they don’t know any better, because they aren’t reading academic history, and don’t talk to academic historians on this topic.

One thing I want to say up front: there are many legitimate interpretations of the atomic bombings. Were they a good thing, or a bad thing? Were they moral acts, or essentially war crimes? Were they necessary, or not? Were they avoidable, or were they inevitable, once the US had the weapons? What would the most likely scenario have been if they weren’t used? How should we think about their legacies? And so on, and so on. I’m not saying you have to subscribe to any one answer to those. However, a lot of people are essentially forced into one answer or another by bad historical takes, including bad historical takes that are systematically taught in US schools. There’s lot of room for disagreement, but let’s make sure we’re all on the same page about the broad historical facts, first. It is totally possible to agree with all of the below and think the atomic bombings were justified, and it’s totally possible to take the exact opposite position.

There was no “decision to use bomb”

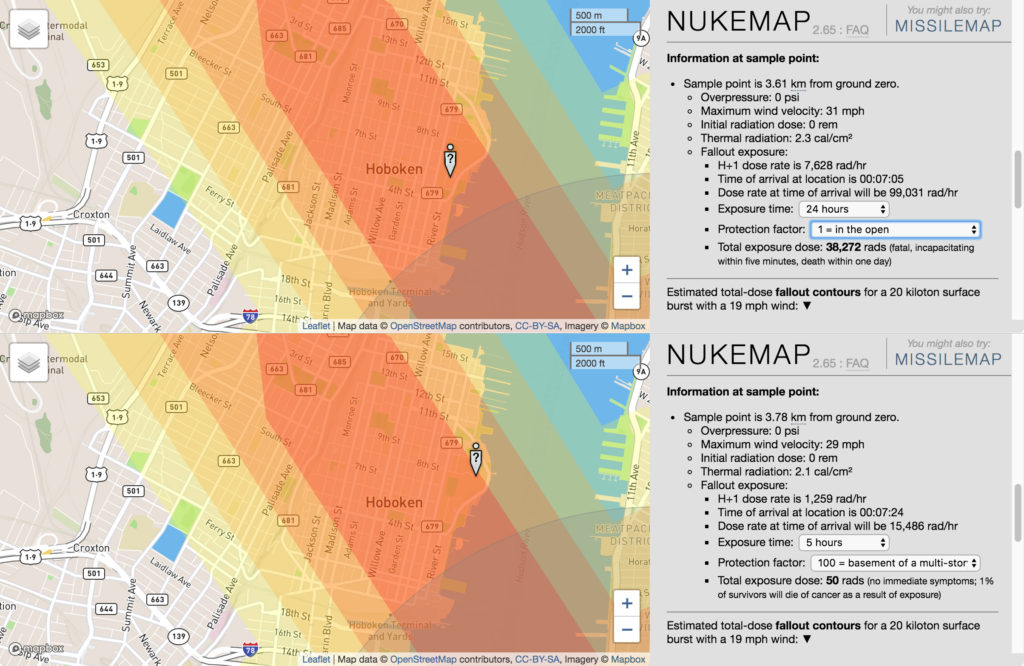

The biggest and most important thing that one ought to know is that there was no “decision to use the atomic bomb” in the sense that the phrase implies. Truman did not weigh the advantages and disadvantages of using the atomic bomb, nor did he see it as a choice between invasion or bombing. This particular “decision” narrative, in which Truman unilaterally decides that the bombing was the lesser of two evils, is a postwar fabrication, developed by the people who used the atomic bomb (notably General Groves and Secretary of War Stimson, but encouraged by Truman himself later) as a way of rationalizing and justifying the bombings in the face of growing unease and criticism about them.

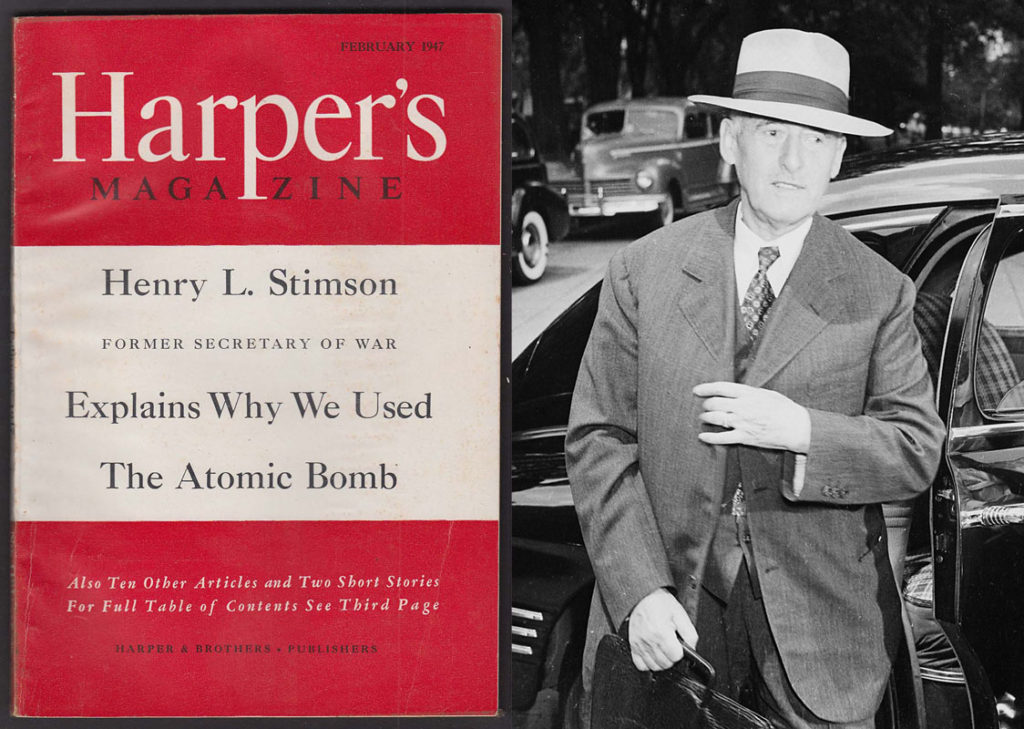

The article in Harper’s by Henry Stimson, published in early 1947, is where the “decision to use the bomb” narrative was first put into its most persuasive and expansive form. I find it is useful to point out that even the “orthodox” narratives have their origins as well — people frequently treat them as if they fell out of the sky or were handed down on tablets.

What did happen was far more complicated, multifaceted, and at times chaotic — like most real history. The idea that the bomb would be used was assumed by nearly everyone who was involved in its production at a high level, which did not include Truman (who was excluded until after Roosevelt’s death). There were a few voices against its use, but there were far more people who assumed that it was built to be used. There were many reasons why people wanted it to be used, including ending the war as soon as possible, and very few reasons not to use it. Saving Japanese lives was just not a goal — it was never an elaborate moral calculus of that sort. Rather than one big “decision,” the atomic bombings were the product of a multitude of many smaller decisions and assumptions that stretched back into late 1942, when the Manhattan Project really got started.

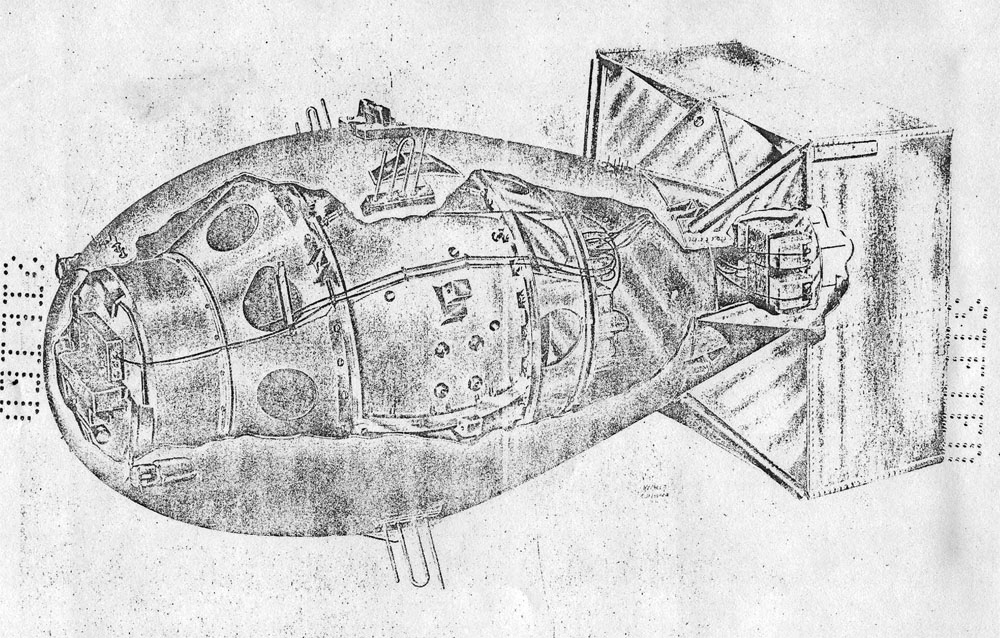

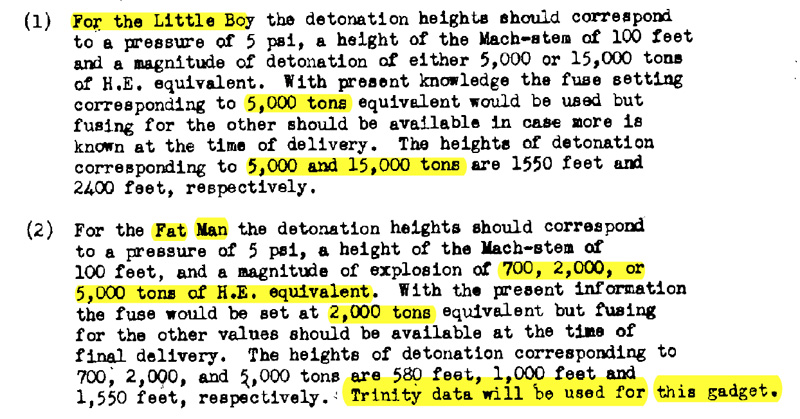

This is not to say there were not decisions made along the line. There were lots of decisions made, about the type of bomb being built, the kind of fuzing used for it (which determines what kinds of targets it would be ideal against), the types of targets… Truman wasn’t part of these. His role was extremely peripheral to the entire endeavor. As General Groves put it, Truman’s role was “one of noninterference—basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.”

Truman was involved in only two major issues relating to the atomic bomb decision-making during World War II. These were concurring with Stimson’s recommendations about the non-bombing of Kyoto (and the bombing of Hiroshima instead), which I have written about (and now published about) at some length. The other is the (not-unrelated, I argue) decision on August 10, 1945, to halt further atomic bombings (at least temporarily) because, as he put it to his cabinet meeting, “the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible. He didn’t like the idea of killing, as he said, ‘all those kids.’”

It was never a question of “bomb or invade”

Part of the “decision” narrative above is the idea that there were only two choices: use the atomic bombs, or have a bloody land-invasion of Japan. This is another one of those clever rhetorical traps created in the postwar to justify the atomic bombings, and if you accept its framing then you will have a hard time concluding that the atomic bombings were a good idea or not. And maybe that’s how you feel about the bombings — it’s certainly a position one can take — but let’s be clear: this framing is not how the planners at the time saw the issue.

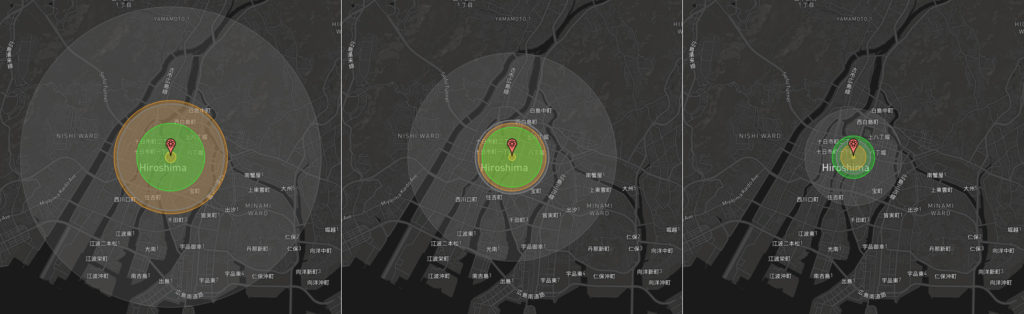

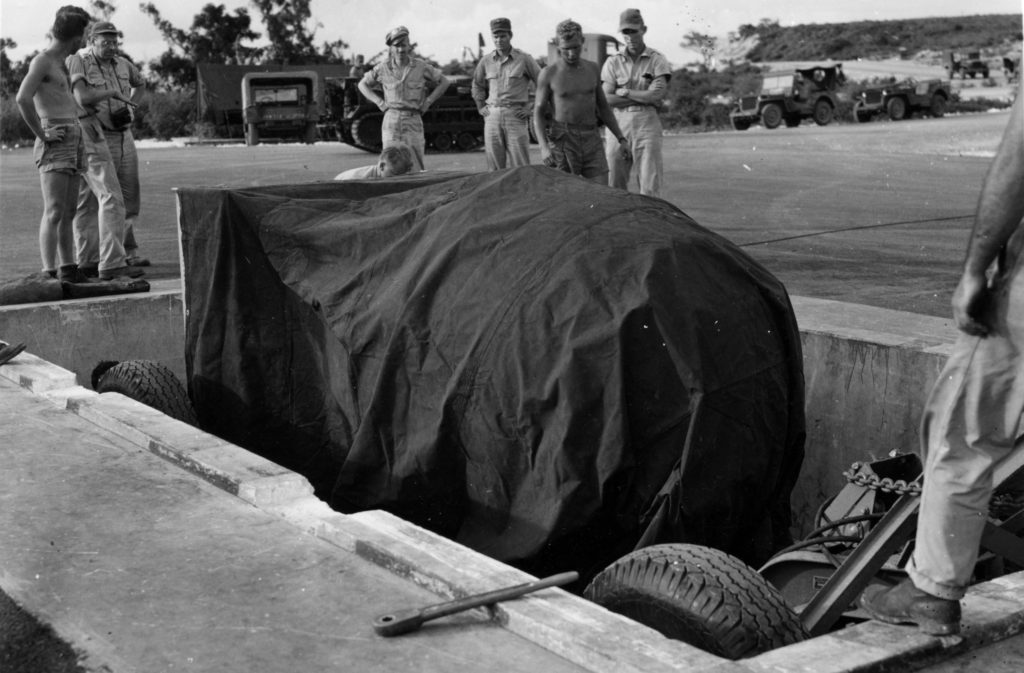

The plan was to bomb and to invade, and to have the Soviet invade, and to blockade, and so on. It was an “everything and the kitchen sink” approach to ending the war with Japan, though there were a few things missing from the “everything,” like modifying the unconditional surrender requirements that the Americans knew (through intercepted communications) were causing the Japanese considerable difficulty in accepting surrender. I’ve written about the possible alternatives to the atomic bombings before, so I won’t go into them in any detail, but I think it’s important to recognize that the way the bombings were done (two atomic bombs on two cities within three days of each other) was not according to some grand plan at all, but because of choices, some very “small scale” (local personnel working on Tinian, with no consultation with the President or cabinet members at all), made by people who could not predict the future.

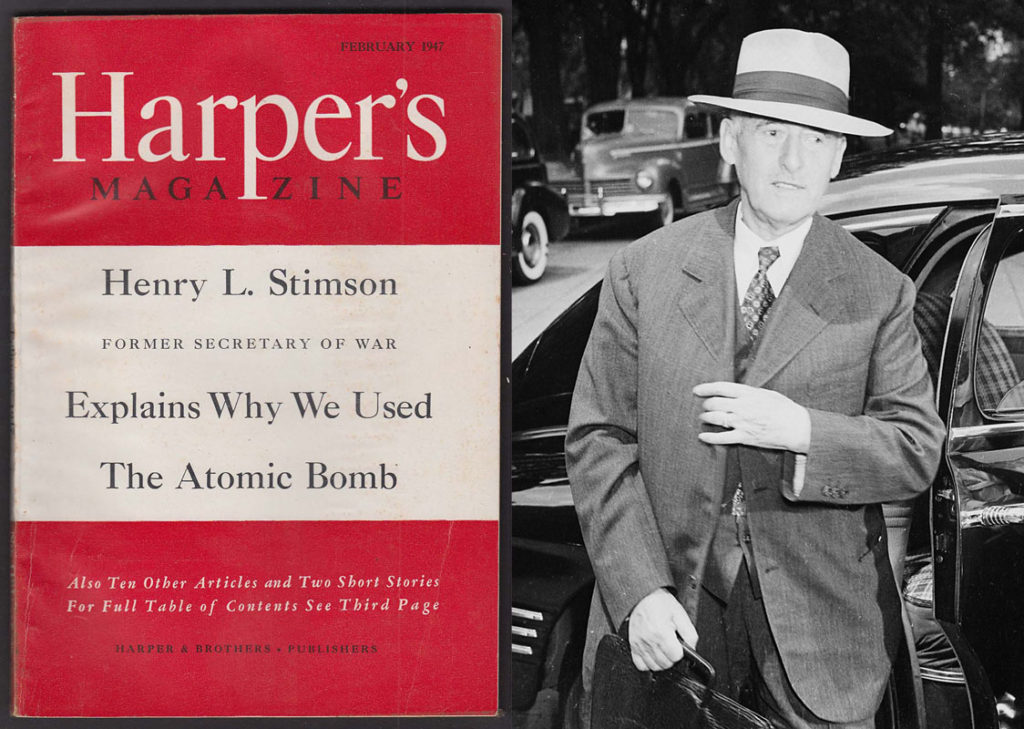

Soldiers on Tinian prepare to load the “Fat Man” bomb for the second atomic bombing mission. Source: National Archives (77-BT-174).

While we are on the subject, we should note that many of the casualty estimates on the invasion have become grossly inflated after the war ended. The estimates that the generals accepted at the time, and related to Truman, were that there would be on the order of tens of thousands of American casualties from a full invasion (and casualties include the injured, not just the dead). That’s nothing to scoff at, but it’s not the hundreds of thousands to even millions of deaths that have sometimes been invoked. Be wary of this kind of counterfactual casualty estimation, especially when it is done in the service of a conclusion that is already agreed upon. It’s easy to imagine the worst-case scenarios that didn’t happen, and to use these to justify the awful things that did happen. This is bad reasoning, and a bad approach to moral thinking — it is a particularly insidious form of “ends justify the means” reasoning which can justify damned near anything in the name of imaginative alternatives.

All that being said, I want to just say that I’m not necessarily saying that other alternatives should have been pursued. That’s not really a position I feel comfortable staking out, only because I can’t predict what would have happened if they had done other things as well. One can easily imagine the Japanese deciding to keep fighting even in spite of everything, just compounding the death and leading into a pretty grim postwar world. Frankly, when one looks at the chaotic Japanese decision-making that went into their actual surrender (more on that in a minute) it is actually quite clear that they only barely surrendered when they did. So I would not want to say, “they should have done it another way” with any confidence. But I do think it is important to point out that none of it was inevitable, and that some of the justifications for why they did it are quite overstated.

Separately, it is worth pointing out, because this is often obscured, that the invasion of Kyushu was not scheduled to begin until November 1945. There are many framings of this that make it look like the invasion was about to start immediately after the atomic bombings, and this just isn’t the case. The invasion of Honshu had not yet been authorized, but would not have begun until early 1946. This doesn’t change whether they would be awful or anything like that, but the tightening of the timeline, to make it seem like both were imminent, is part of the rhetorical strategy to justify using the atomic bombs.

There were many reasons that the Americans wanted to drop the atomic bombs

There are two main explanations given to why the Americans dropped the atomic bombs. One is the “decision to use the bomb” narrative already outlined (end the war to avoid an invasion). The other, which is common in more left-leaning, anti-bombing historical studies, is that they did it to scare the Soviet Union (to show they had a new weapon). This latter position is sometimes called the Alperovitz thesis, because Gar Alperovitz did a lot of work to popularize and defend it in the 1980s and 1990s. It’s older than that, for whatever that is worth.

Time magazine covers from 1945: Stalin, Truman, Hirohito. Each kind of tacky in their own way.

When I talk to students about the atomic bombings, I usually have them tell me what they know of them. Maybe 80% know the “decision to use the bomb” narrative (we could probably call this the Stimson narrative if we wanted to be consistent). I chart this out on the whiteboard, highlighting the key facts of it. A few in each class know the Alperovitz narrative, which they got from various alternative sources (like Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick’s The Untold History of the United States documentary). We then discuss the implications of each — what does believing in either make you feel about World War II, the atomic bombings, about the United States as a world power today?

And then I tell them that historians today tend to reject both of these narratives. Which makes them want to throw their hands up in frustration, I am sure, but that’s what scholarship is about.

I’ve written a bit on this in the past, but the short version is that historians have found that both of these narratives are far too clean and neat: they both assume that the nation had a single driving purpose in using the atomic bombs. This isn’t the case. (And, spoiler alert, it’s almost never the case.) As already noted, the process had many different parts to it, and no single “decision” at all, and so one can find historical figures who had many different perspectives. What is interesting is that for those involved in the making of the bomb, and the highest-level decisions about its use, almost all of those perspectives converged on the idea of using it.

So there certainly were people who hoped it would end the war quickly to avoid invasion. There were also those who hoped it would end the war before the Soviets declared war on the Japanese, giving the US a freer hand in Asia in the postwar period. (More on that in a moment.) There were also those who considered it “just another weapon” and attached no special significance to its use. And there were those who took the entirely opposite approach, seeing it as a herald of a future nuclear arms race, and who believed that the best first use of the bomb ought to be the one that laid bare its horrible spectacle. (Personally, I find this position the most historically and intellectually interesting — the idea that by using the bombs on cities in World War II, you’d prevent nuclear weapons from being ever used in anger again.)

And there were those who thought that one of the “bonuses” of using the bomb was to scare the Soviets. It’s not just a “revisionist” (a term I hate) idea — one can document it pretty easily (and Alperovitz does). This strain of thinking was particularly prominent in the thinking of Secretary of State James Byrnes, whose advocacy of “atomic diplomacy” against the Soviets was explicit. It’s not a goofy idea. The question is whether it is the whole story — and it’s not.

Where both the Stimson and Alperovitz narratives fail is that they insist that there were only singular reasons to use the atomic bomb. But there were many people involved with it, and thus many different motivations. That’s not a problem if you want to argue for or against the atomic bombings — but implying it is just one or the other is a misrepresentation of this history, and also of how people generally operate. People are complicated.

It isn’t clear the atomic bombs ended World War II

My least favorite way in which the end of World War II is discussed goes along these lines: “The atomic bombs ended World War II.” My second-least favorite way is a weaker variant that is becoming more common: “A few days after the atomic bombs were dropped, the Japanese surrendered.” Note the latter doesn’t really say the bombs did it… but implies it very strongly.

Scholars have known for a long time that the end of World War II was an immensely complicated event. Several events happened within the space of a few days, including:

- The bombing of the city of Hiroshima

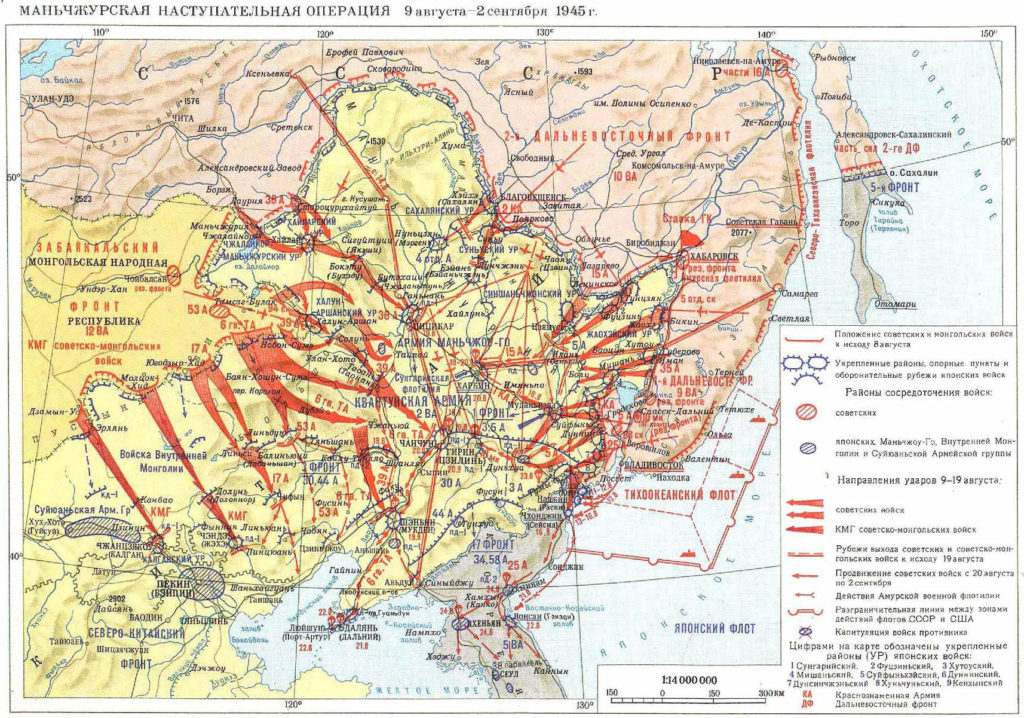

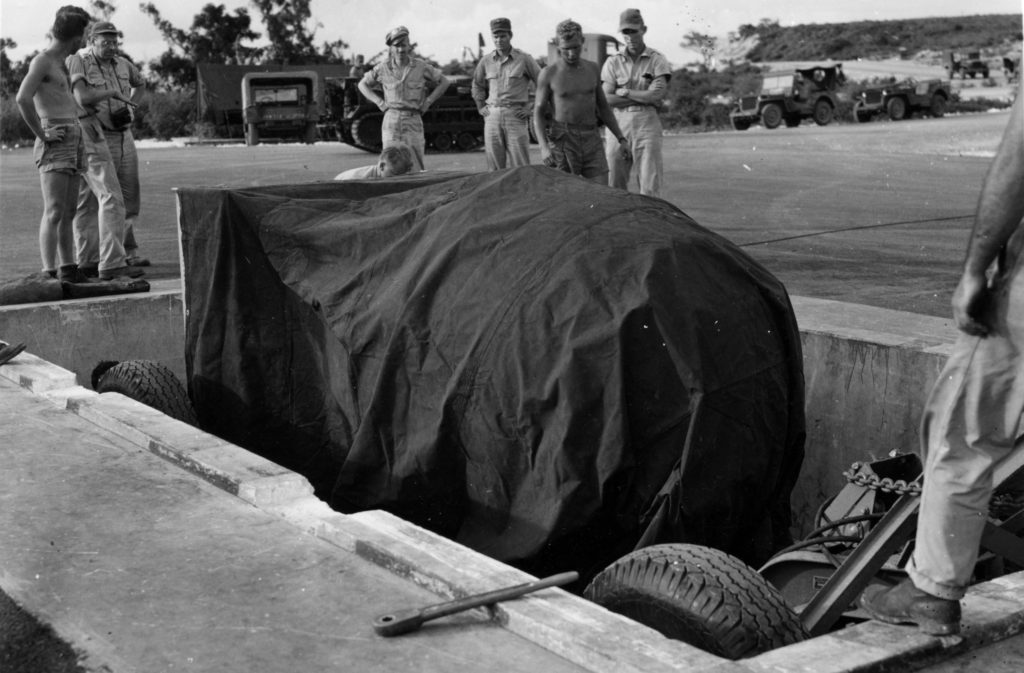

- The Soviet declaration of war against the Japanese, and subsequent invasion of Manchuria

- The bombing of the city of Nagasaki

- Internal friction within the Japanese high command

- An attempted coup by junior military officers

- An offer of surrender that still maintained the status of the Emperor

- A rejection of this offer by the Americans

- An increase of American conventional bombing

- An acceptance of unconditional surrendered by the Emperor himself

If I tried to write out all of the events that the above encapsulate, this post would get very long indeed. The point I want to make, though, is that it isn’t some simple matter of “atomic bombs = unconditional surrender.” Even with two atomic bombs and the Soviet invasion, the Japanese high command still didn’t offer unconditional surrender! It was a very close thing all around, and it strikes me as impossible to totally disentangle all of the causes of their surrender.

I think it is fair to say that the atomic bombs played a role in the Japanese surrender. It is clear they were one of the issues on their mind, both those in the military who wanted the country to resist invasion as bloodily as possible (with the hope of making the Allies accept more favorable terms for Japan), and those who wanted a diplomatic end of the war (though even those did not imagine accepting unconditional surrender — they wanted to preserve the imperial house).

Russian image of the Soviet invasion of Manchuria, 9 August-2 September 1945. There’s something about all that red that, I think, underscores how disastrous the Japanese would have seen this.

It is also clear that the Soviet declaration of war and subsequent invasion of Manchuria loomed largely in all of their minds as well. Which is more important? Could we imagine the same results occurring if one hadn’t occurred? I don’t know. It’s complicated. It’s messy. Like the real world.

There are some who believe the war could have been ended without the atomic bombings (especially the bombing of Nagasaki, which does not appear to have changed things in the minds of the Japanese high command). I’ve never been totally convinced of their arguments; they strike me as a bit overly optimistic. But I think it is also clear that the Soviet role deserves far more attention than it typically gets in American versions of this story; it is easy to document its impact. And then again, one can ask how much would have been changed if the unconditional surrender requirement had been modified earlier on, like some American advisors had urged. The tricky thing about history, though, is you can’t just rewind it, change a few variables, and run it forward again. So it’s hard to have any confidence about such predictions.

Still, it’s worth noting that the relationship between the atomic bombs and the Japanese surrender is a complicated one. In the US, claiming the atomic bombs ended the war has historically been a way of writing the Soviets out of the picture, as well as making the case for the use of the bombs stronger. I think both of these make for bad history.

The bombings were controversial in their time

While the majority of Americans supported the atomic bombings at the time — they were, after all, told they had ended World War II, saved huge numbers of lives, and so on — it is worth just noting that approval was not universal, and that people questioning whether they had to be used, or whether they had ended World War II, were not fringe. Some of the most critical voices about the atomic bombings came from military figures who, for a variety of reasons, would come out against the bombings in the years afterwards. The US Strategic Bombing Survey, a military-led assessment of bombing effectiveness in World War II, concluded in July 1946 that:

Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no [American] invasion had been planned or contemplated.

Which is a pretty shocking statement to read! I’m not saying you have to agree with it; you’re not bound by isolated judgments of the past, and there are good reasons to doubt the reasoning of the USSBS (they were acting in part out of fear that the atomic bombs would overshadow conventional bombing efforts and undercut their desire for a large and independent Air Force). But I think it is useful to point out that doubtful voices are not a recent thing, nor are they exclusively associated with the “obvious” points of views (like those sympathetic to Communism or the Soviets). The past is complicated, and the people in the past were complicated as well. I have frequently observed that the people who tell us not to impose present-day judgments on the past are unaware that many of these same judgments were made in the past as well.

In conclusion: talk to historians!

Nothing I have written above is, I don’t think, terribly unknown to historians doing active work on this topic. They might have different takes on these things than I do (in fact, I know many of them do), and that’s fine. Historians disagree with each other. That’s part of the fun of it, and why it is an active area of research. There are lots of historical interpretations, lots of historical narratives, lots of juicy stories and hot takes.

But you wouldn’t know this from most historical coverage of the atomic bombings, especially when anniversaries roll around. There are probably non-insidious reasons for this. I get that journalists don’t have time to read every piece of scholarship that has come out since the last 5 year anniversary, or even since the 1990s (most of the mythical discussions are stuck in the “culture wars” version of the atomic bomb story, best exemplified by the Smithsonian’s Enola Gay controversy of 1995). Journalists work on lots of topics, I get it.

Something I saw for sale at a gift shop in the Grand Prince Hotel, Hiroshima, in 2017. Aside from its oddness, I like to use it when teaching to talk about how the bombings can mean different things to different people — this is the Hiroshima dome as a symbol of peace, not a symbol of destruction.

But journalists — you can reach out to us! There are many historians doing interesting work on these topics. Just get in touch. We’ll talk to you. And one question you should always ask any historians you contact is: “who else should I talk to?” Because some of us historians are more prominent than others (in that our names and websites come up when you Google them), but that doesn’t mean we’re the only ones out here. We’ll happily put you in touch with scholars who are well-known within our discipline, but harder to see outside of it. Because they’ve got interesting things to say, too.

And if you really aren’t sure who those might be, the author list of this 2020 volume from Princeton University Press (in which I published my article on Kyoto) is a good place to start!

Why do this? Because a) it’s better history, b) these historical narratives are tied to a lot of other narratives (like debates about the morality of war, for example), and c) because provocative, interesting, hot stories will practically write themselves if you talk to scholars working on the cutting-edge of this work. Let us help you! It’s win-win!

There are other things, of course, that a journalist ought to know — but these things, for me, stand out the most as the “big picture” issues that I still see coming up again and again, despite the fact that the scholarship has been beyond them for decades now. Those who do not know the past, at the very least, are in danger of repeating the same bad versions of the past…!

General news update: The COVID-19 crisis dramatically complicated my teaching and research productivity over the last semester, and I’ve been digging myself out of a work-hole ever since. The good news is that some very interesting things are in the works. And I should be posting a few more blog posts this summer!