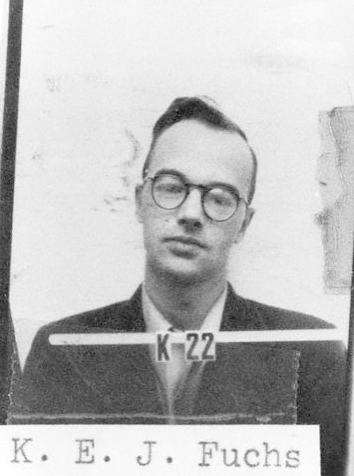

Recently — sometime in the last year — the FBI revamped its online FOIA Reading Room and replaced it with a new website called the FBI Vault. Somehow I missed this until just this week. The Vault contains all of the files the old Reading Room had, but adds a huge, new section on the Rosenberg Case. This is pretty great, both for Cold War historians, as well as a potential font for student papers. Along with those of the eponymous couple, these include the files of Klaus Fuchs, Harry Gold, David Greenglass, George Kistiakowski (misspelled online), J. Robert Oppenheimer (not his entire file), Morton Sobell, Harold Urey (not his entire file), among many others. Note that in some cases they are not the full files. Oppenheimer’s file there is just the parts that were considered relevant to the Rosenberg Case. It’s a lot of this-and-that, and not the full file by a long shot. Same with Urey’s and Kistiakowski’s files. At some point in the late 1970s, it seems that a number of files were either culled or grouped together with respects to a court order, and you can see evidence of this in the files as they have long lists of documents not enclosed, dated from 1978 or so.

Still, the Fuchs file is a full 9,923 pages (760MB!) of FBI-file-goodness, all conveniently in PDF format. It’s not quite identical to what I got by FOIAing the FBI a few years ago — the CD-ROM the FBI sent me had 839 more pages in it — but it’s still pretty impressive. (If you’re interested in downloading the files in bulk, I heavily recommend using a download manager, like Download Them All for Firefox. It makes downloading 111 PDF files a lot easier, even though it does still take some fiddling, since the FBI wasn’t entirely consistent with how it uploaded these files.)

Of course, the Vault site also contains the files of Groucho Marx, Liberace, and an 119 page file on “Louie, Louie,” the song (the FBI, like everyone else, couldn’t figure out the lyrics), so there’s no shortage of fun to be had there. I’ve added this resource to my long list of nuclear primary sources on the web.

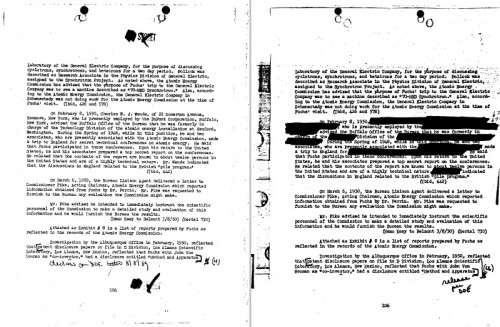

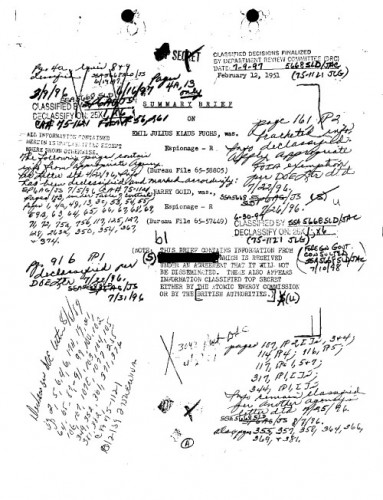

This week’s document comes from the Fuchs file linked to above. Specifically, it’s an excerpt of a February 1951 report made by the FBI titled “Summary Brief on Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs,” related to “Fuchs’ Scientific Knowledge and Disclosures to Russians.”1

Now this is, to me anyway, a pretty interesting document in and of itself. It compiles a lot of information about what exactly Fuchs claims to have given to the Russians. It’s limited, though, in part because of the fact that the British weren’t keen on giving the Americans unfettered access to Fuchs.2

But what seals it for me is that the Fuchs file, as posted to the FBI Vault, actually contains two differently-redacted versions of the same file. Now, I love differently-redacted documents. Not just because I get to see what was under all that black ink, but because I get to see what earlier declassifiers considered to be secret. For a student of secrecy, this is the top of the tops: you not only get to know what used to be considered a secret, but you get to see how a redactors isolated it from its surrounding context. This sort of information is highly revealing to the way in which the classification mindset changes over time.3

Pages 24 and 48 in the above PDF file, side by side, both showing page 106 of the original document.

I’ve included snippets of the different pages in the PDF linked above. The more heavily-redacted version seems to have been declassified in 1987, the less-redacted version in 1996, judging from the stamps on the front of the documents.

In this particular case, most of what was being removed falls into the categories of people who were probably still alive at the time of the declassification, and, more interestingly, any reference to British sources of information at all.

Why would the latter be secret? I mean, who else was supposed to be feeding the FBI information about Fuchs’ activities? Well, the CIA and the State Department generally don’t want information circulating about how other countries have fed them information until the other countries in question concur with the declassification. Even the existence of MI-5 seems to have been officially a secret until relatively recently, even though it was an obviously “open secret.” The 1996 version has direct references to MI-5 in it, something you won’t find in things declassified before the end of the Cold War.

This sort of jigsaw-puzzle game of classification must drive the security people nuts. Ideally secrecy is meant to make something less prominent, but of course once you know something was a secret, it becomes more interesting.

- Citation: Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Summary Brief on Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs” (12 February 1951), (Excerpt), in Klaus Fuchs FBI file, FBI Vault version. [↩]

- For a really terrific account of the tensions in the FBI-MI5 relationship regarding Fuchs, see Michael S. Goodman, “Who Is Trying to Keep What Secret from Whom and Why? MI5-FBI Relations and the Klaus Fuchs Case,” Journal of Cold War Studies 7, no. 3 (Summer 2005), 124-146. [↩]

- This isn’t the same thing as using different, contemporary versions of redacted files to ferret out information that may or may not still be currently considered secret. I’ll talk about that another time… [↩]

[…] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Summary Brief on Emil Julius Klaus Fuchs” (12 February 1951), (Excerpt), in Klaus Fuchs FBI file, FBI Vault version., via Restricted Data […]