No single nuclear weapons test did more to establish the grim realities of the thermonuclear age than Castle BRAVO. On March 1, 1954, it was the highest yield test in the United States’ highest-yield nuclear test series, exploding with a force of 15 million tons of TNT. It was also the greatest single radiological disaster in American history.

Castle BRAVO, 3.5 seconds after detonation, photo taken from a distance of 75 nautical miles from ground zero, from an altitude of 12,500 feet. From DTRIAC SR-12-001.

Among BRAVO’s salient points:

- It was the first “dry fuel” hydrogen bomb test by the United States, validating that lithium-deuteride would work fine as a fusion fuel and making thermonuclear weapons relatively easy to deploy.

- It had a maximum predicted yield of only 6 megatons — so it was 250% as explosive than was expected.

- And, of course, it became famous for raining nuclear fallout down on inhabited islands over a hundred miles downwind, and exposing a crew of Japanese fishermen to fatal levels of radiation.

It was this latter event that made BRAVO famous — so famous that the United States had to admit publicly it had a hydrogen bomb. And accidentally exposing the Japanese fishing supply to radiation, less than a decade after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, has a way of making the Japanese people understandably upset. So the shot led to some almost frank discussion about what fallout meant — that being out of the direct line of fire wasn’t actually good enough.

Animation showing the progression of BRAVO’s fallout exposure, at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 hours. Original source.

I say “almost frank” because there was some distinct lack of frankness about it. Lewis Strauss, the secrecy-prone AEC Chairman at the time and an all-around awful guy, gave some rather misleading statements about the reasons for the accident and its probable effects on the exposed native populations. His goal was reassurance, not truth. But, as with so many things in the nuclear age, the narrative got out of his control pretty quickly, and the fear of fallout was intensified whether he wanted it to be or not.

We now know that the Marshallese suffered quite a lot of long-term harm from the exposures, and that the contaminated areas were contaminated for a lot longer than the AEC guessed they would be. Some of this discrepancy comes from honest ignorance — the AEC didn’t know what they didn’t know about fallout. But a lot of it also came from a willingness to appear on top of the situation, when the AEC was anything but.

“Jabwe, the Rongelap health practitioner, assists Nurse Lt. M. Smith and Dr. Lt. J. S. Thompson, during a medical examination on Kwajalein, 11 March 1954.” From DTRIAC SR-12-001.

I’ve been interested in BRAVO lately because I’ve been interested in fallout. It’s no secret that I’ve been working on a big new NUKEMAP update (I expect it to go live in a month or so) and that fallout is but one of the new amazing features that I’m adding. It’s been a long-time coming, since I had originally wanted to add a fallout model a year ago, but it turned out to be a non-trivial thing to implement. It’s not hard to throw up a few scaled curves, but coming up with a model that satisfies the aesthetic needs of the general NUKEMAP user base (that is, the people who want it to look impressive but aren’t interested in the details) and also has enough technical chops so that the informed don’t just immediately dismiss it (because I care about you, too!) involved digging up some rather ancient fallout models from the Cold War (even going out to the National Library of Medicine to get one rare one in its original paper format) and converting them all to Javascript so they can run in modern web browsers. But I’m happy to say that as of yesterday, I’ve finally come up with something that I’m pleased with, and so I can now clean up my Beautiful Mind-style filing system from my office and living room.

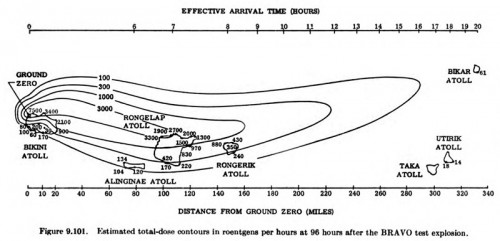

The most famous version of BRAVO’s total-dose exposure contours, from Glasstone and Dolan. It looks great on a mug, by the way.

Recently I was sent a PDF of a recent report (January 2013) by the Defense Threat Reduction Information Analysis Center (DTRIAC) that looked back on the history of BRAVO. It doesn’t seem to be easily available online (though it is unclassified), so I’ve posted it here: “Castle Bravo: Fifty Years of Legend and Lore (DTRIAC SR-12-001).” I haven’t had time to read the whole thing, but skipping around has been rewarding — it takes a close look at the questions of fallout prediction, contamination, and several “myths” that have circulated since 1954. It notes that the above fallout contour plot, for example, was originally created by the USAF Air Research and Development Command (ARDC), and that “it is unfortunate that this illustration has been so widely distributed, since it is incorrect.” The plume, they explain, actually under-represents the extent of the fallout — the worst of the fallout went further and wider than in the above diagram.

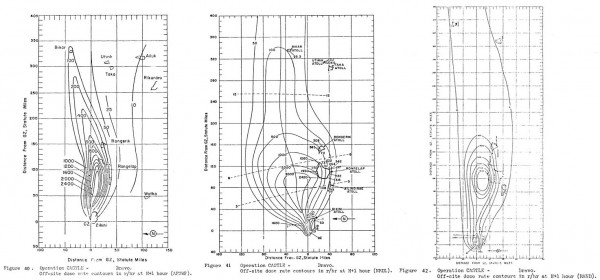

You can get a sense of the variation by looking at some of the other plots created of the BRAVO plume:

BRAVO fallout contours produced by the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory, and the RAND Corporation. Source. Click image to enlarge.

The AFSWP diagram on the left is relatively long and narrow; the NRDL one in the middle is fat and horrible. The RAND one at the right is something of a compromise. All three, though, show the fallout going further than the ADRC model — some 50-100 miles further. On the open ocean that doesn’t matter so much, but apply that to a densely populated part of the world and that’s pretty significant!

DTRIAC SR-12-001 is also kind of amazing in that it has a lot of photographs of BRAVO and the Castle series that I’d never seen before, some of which you’ll see around this post. One of my favorites is this one, of Don Ehlher (from Los Alamos) and Herbert York (from Livermore) in General Clarkson’s briefing room on March 17, 1954, with little mockups of the devices that were tested in Operation Castle:

There’s nothing classified there — the shapes of the various devices have long been declassified — but it’s still kind of amazing to see of their bombs on the table, as it were. They look like thermoses full of coffee. (The thing at far left might be a cup of coffee, for all that I can tell — unfortunately the image quality is not great.)

It also has quite a lot of discussion of several persistent issues regarding the exposure of the Japanese crew and the Marshallese natives. I didn’t see anything especially new here, other than the suggestion that the fatality from the Fortunate Dragon fishing boat might have been at least partially because of the very aggressive-but-ineffective treatment regime prescribed by the Japanese physicians, which apparently included the very dubious procedure of repeatedly drawing his blood and then re-injecting it into muscle tissue. I don’t know enough of the details to know what to think of that, but at least they do a fairly good job of debunking the notion that BRAVO’s contamination of the Marshallese was deliberate. I’ve seen that floating around, even in some fairly serious forums and publications, and it’s just not supported by real evidence.

![Castle BRAVO, 62 seconds after detonation. "This image was take at a distance of 50 [nautical miles] north GZ from an altitude of 10,000 feet. The lines running upward to the left of the stem and below the fireball are smoke trails from small rockets. At this time the cloud stem was about 4 mi in diameter." From DTRIAC SR-12-001.](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Bravo-at-62-seconds-crop.jpg)

Castle BRAVO, 62 seconds after detonation. “This image was take at a distance of 50 [nautical miles] north GZ from an altitude of 10,000 feet. The lines running upward to the left of the stem and below the fireball are smoke trails from small rockets. At this time the cloud stem was about 4 mi in diameter.” From DTRIAC SR-12-001.

It was detonated as a surface burst, which automatically means quite a significant fallout problem. Nuclear weapons that detonate so that their fireball does not come into contact with the ground release “militarily insignificant” amounts of fallout, even if their yields are very high. (They are not necessarily “humanly insignificant” amounts, but they are far, far, far less than surface bursts — it is not a subtle difference.2 )

But even worse, it was a surface burst in a coral reef, which is just a really, really bad idea. Detonating nuclear weapons on a desert floor, like in Nevada, still presents significant fallout issues. But a coral reef is really an awful place to set them off, and not just because coral reefs are awesome and shouldn’t be blown up. They are an ideal medium for creating and spreading contamination: they break apart with no resistance, but do so in big enough chunks that they rapidly fall back to Earth. Particle size is a big deal when it comes to fallout; small particles go up with the fireball and stay aloft long enough to lose most of their radioactive energy and diffuse into the atmosphere, while heavy particles fall right back down again pretty quickly, en masse. So blowing up and irradiating something like coral is just the worst possible thing.3

Castle BRAVO, 16 minutes after detonation, seen from a distance of 50 nautical miles, at an altitude of 10,000 feet. From DTRIAC SR-12-001.

Note that the famous 50 Mt “Tsar Bomba” lacked a final fission stage and so only 3% of its total yield — 1.5 Mt — was from fission. So despite the fact that the Tsar Bomba was 3.3 times as explosive than Castle Bravo, it had almost 7 times fewer fission products. And its fireball never touched the ground (in fact, it was reflected upwards by its own shock wave, which is kind of amazing to watch), so it was a very “clean” shot radiologically. The “full-sized,” 100 Mt Tsar Bomba would have been 52% fission — a very dirty bomb indeed.

In the end, what I’ve come to take away from BRAVO is that it actually was a mistake even more colossal than one might have originally thought. It was a tremendously bad idea from a human health standpoint, and turned into a public relations disaster that the Atomic Energy Commission never really could kick.

In retrospect the entire “event” seems to have been utterly avoidable as a radiological disaster, even with all of the uncertainties about yield and weather. It’s cliché to talk about nuclear weapons in terms of playing with “forces of nature beyond our comprehension,” but I’ve come to feel that BRAVO is a cautionary tale about hubris and incompetence in the nuclear age — scientists setting off a weapon whose size they did not know, whose effects they did not correctly forecast, whose legacy will not soon be outlived.

- Chuck Hansen, Swords of Armageddon, IV-299. [↩]

- The count difference is about three orders of magnitude or so less, judging by shots like Redwing CHEROKEE. That’s still a few rads, but the difference between 1,000 and 1 rad/hr is pretty significant. [↩]

- Couldn’t they have foreseen this? In theory, yes — they had already blown up a high-yield, “dirty” fission hydrogen bomb on a coral reef in 1952, the MIKE test. But somewhere a number of AEC planners seem to have gotten their wires crossed, because a lot of them thought that MIKE had very little fallout, when in fact it also produced a lot of very similar contamination. Unlike BRAVO, however, MIKE’s fallout blew out over open sea. The only radiation monitoring seems to have been done on the islands, and so they don’t seem to have ever drawn up one of those cigar-shaped plumes for it. See e.g. the discussion here on page 51. [↩]

Samples from the fishing boat also allowed Rotblat to figure out how an H-bomb worked, which really upset the Americans at the time. You can read a bit about it at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1387592

Thanks, Paul. One can read Rotblat’s write-up of the fission-fusion-fission mechanism here. It is pretty good for 1955!

Weird illustrations for a scientific magazine, especially one with this topic. Seems more fitting for a children’s book or something.

For NUKEMAP, the problem of estimating the spatial distribution of a fallout cloud must be highly complex, since prevailing winds, atmospheric and so on will play a major role. One place to look is the work of Alan Robock, a climate scientist whose done a lot of work on volcanic plume effects as well as the nuclear winter scenario:

http://climate.envsci.rutgers.edu/robock/robock_nwpapers.html

The Northen Islands of Rongelap Atoll which recieved a life-threatening deposition of radioactive fallout from the Bravo shot remains “forbidden territory” .Also, several other shots in the 1954 Castle test series added signficantly to radiological contamination.

Below is testimony I delivered before a subcommittee of the House Foreign Affairs in 2010 about the radiological legacy of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands.

http://www.ips-dc.org/files/2024/Alvarez_testimony-Nuclear_Legacy.pdf

In Lorna Arnold’s book “Britain and the H-Bomb” there is a short paragraph on Castle Bravo

where she writes (pag.18): “The reason for the miscalculation was that the weaponeers at Los Alamos had considered only the lithium-6 content and ignored an important fusion reaction in the lithium-7 which makes up 60% of the total lithium. They sent a last minute warning when they realised the error, but it reached the trials staff at Eniwetok too late. (emphasis mine).

I’ve always been curious about the “last minute warning” story, but i’ve never found it in any other document beside her book. What is your take on it?

That’s a curious account; I’ll do a little snooping around.

But my understanding was that they did not ignore lithium-7 accidentally, but that they were unsure whether lithium-7 would actually ignite well. They were already planning to try a test of nothing but lithium-7 well before BRAVO, but they didn’t think it would give good results. So they must have at least done some preliminary calculations on the expected burn-rate of lithium-7 — “ignored” can’t be correct.

Agreed, maybe “ignored” sounds way too strong to be the correct description but my guess is that maybe they looked at the Q of the reaction (I haven’t doublechecked but wiki gives Q= 4.784 MeV for neutron+lithium-6->tritium+helium, but Q= – 2.467 MeV for neutron+lithium-7->tritium+helium+neutron) and decided that, at least for a rough approximation, the Li7 reaction was negligible for the yield calculation. But the neutrons’ surplus will breed more tritium and (more importantly?) fissile more U238 so the final yield was in the upper end of the spectrum.

Anyway, i hope you find out something about the “last minute warning” story, i’ve always find it puzzling.

Any news on your research on gnomon/sundial? That’s another topic i’d love to read more about.

A somewhat redacted discussion of CASTLE series yield uncertainties:

http://www.hss.energy.gov/healthsafety/ihs/marshall/collection/data/ihp1a/0943_.pdf

Also

http://www.hss.energy.gov/healthsafety/ihs/marshall/collection/data/ihp1d/400937e.pdf

Thanks, very interesting docs, it’s unfortunate that they’re still so redacted after 60 years.

“Mixing” is probably Rayleigh instability in the secondary, i guess it was very difficult model such a nonlinear regime with the computing powers available in 1953. Any idea which devices correspond to the yield predicted in that doc?

I haven’t tried to match the predicted yields with devices yet, but there’s a table on p.11 of the minutes of the 41st GAC meeting in July 1954 that gives a table of expected vs measured yields for the CASTLE shots that should help sort that out.

http://www.hss.energy.gov/healthsafety/ihs/marshall/collection/data/ihp1d/73403e.pdf

Expected yield range, MT Measured yield, MT

4-8 15+-0.5

1-7 11+-0.5

1-6 7+-0.5

ca. 11 13.5+-1.0

ca. 2(1.7) 1.7+-0.3

1-4 0.13+-0.03

Thanks!

Following up on the superweapons and climate reference in the DTRA document leads to

Effects of Superweapons Upon the Climate of the World

http://www.hss.energy.gov/healthsafety/ihs/marshall/collection/data/ihp1d/400453e.pdf

Which is in a collection that contains additional scads of BRAVO and other nuclear documents:

http://www.hss.energy.gov/HealthSafety/IHS/marshall/collection/

Radiological Survey of Downwind Atolls Contaminated by BRAVO

12 March 1954

http://www.hss.energy.gov/healthsafety/ihs/marshall/collection/data/ihp1c/0550_a.pdf

hi Mr alex ,,,,,, i enjoy reading about atomic history and Two years ago, I started to translate your articles into Persian ,,, keep doing man ,,,thanks

Off topic, but figured it would be interesting

Declassified by the NSA on May 29 and posted online on Monday, the 344-page report “It Wasn’t All Magic: The Early Struggle to Automate Cryptanalysis, 1930s – 1960s,” details the unknown high-tech history of computers so secretive even their code names were kept confidential

http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2013/06/26/declassified-govt-report-details-decades-nsa-computer-spying/

The main server was swamped, but a good mirror is at

http://archive.org/details/NSA-WasntAllMagic_2002

[…] of 100%, but for thermonuclear weapons it can vary quite a bit. I’ve talked about this in a recent post, so I won’t go into detail here, but just emphasize that it was unintuitive to me that the 50 […]

Some years ago I ran across a newspaper account of the Castle Bravo firing crew’s experience. The piece was overly dramatic, “DEADLY FALLOUT RADIATION TRAPS SCIENTISTS,” but it was interesting and I’ve been on the lookout for a more measured account since. Might make a good subject for your fine blog some time.

[…] en cuenta de lo que estamos hablando. Y no fue lo único que se salió del guión: Castle Bravo es el mayor desastre radiológico de la historia de EEUU, con un resultado de pérdida de vidas humanas, contaminación duradera de […]

[…] when you are talking about millions of tons of TNT (something learned by the US a year earlier, at the Castle Bravo test). The inhabitants of the town were in a primitive bomb shelter. After the flash, they exited to see […]

[…] March 1, 2014, is the 60th anniversary of the Castle Bravo nuclear test. I’ve written about it several times before, but I figured a discussion of why Bravo matters was always welcome. Bravo was […]

[…] isn’t that great. The whole sequence represents less that a minute of the bomb detonation; as I’ve noted previously, most of our photos of mushroom clouds are from the first minute or so after their detonation, and […]