One of the several projects that has been keeping me busy for the past two years (!) has finally come to fruition. I haven’t talked about it on here much, but I’ve been a co-curator at the Intrepid Sea, Air, and Space Museum, in New York City, helping develop a new exhibit about the submarine USS Growler. The exhibit, A View From the Deep: The Submarine Growler and the Cold War, opens to the public on May 11.

I’ve worked with museums a bit in the past, but never anything quite as intensive and comprehensive as this job. The Intrepid has had the Growler submarine since 1988, and a somewhat small exhibit had been developed to serve as a queuing area for people who wanted to go aboard the submarine. But since this year is the 60th anniversary of the commissioning of the boat, as well as the 75th anniversary of the commissioning of the USS Intrepid, the aircraft carrier that serves as the main space of the museum, it was decided that Growler deserved a new, far more comprehensive exhibit dedicated to it.

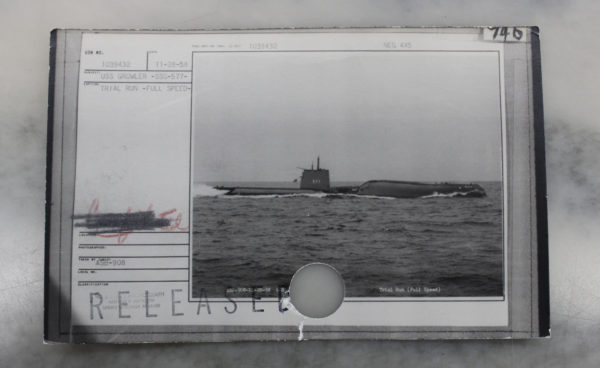

What’s interesting about the Growler? The bare basics: The USS Growler is the only surviving example of the Grayback class of submarine, which was the first nuclear-armed submarine class that the United States fielded. Its deployment was relatively short (1958-1964), in part because it was extremely transitional technology. The Growler was essentially a diesel attack submarine that was modified (by adding some awkward hangers onto its nose) to carry the Regulus I nuclear-armed cruise missile, and ran deterrence missions in the Pacific, near Kamchatka peninsula (its target was a Soviet military base at Petropavlovsk).

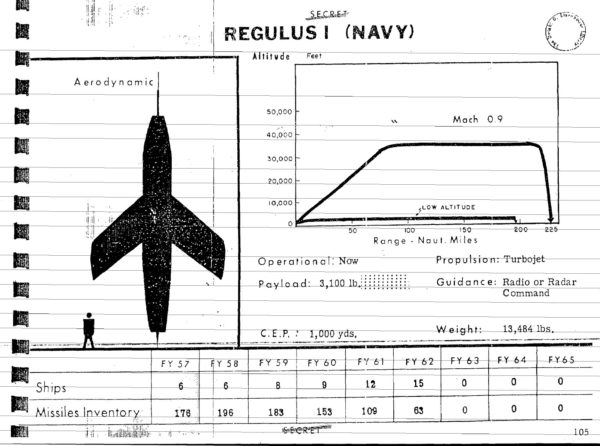

As a diesel sub, its capabilities were pretty limited. It could stay underwater for the duration of its run, through the use of its schnorkel, but it couldn’t dive deep for very long. The Regulus missiles had extreme limitations: they could only be launched from a surfaced ship, had very limited range on account of their guidance systems (they required active radar guidance all the way to their targets, and the guidance system only had a range of around 225 nautical miles). It was always seen as a partial solution, an entry point for the Navy’s foray into nuclear weapons.

The USS Growler on a full-speed trial run, November 1958. The bulbous bow contains hangers that contained Regulus missiles. The Growler was initially designed as an attack submarine, and the hangers were a modification to turn it into a cruise missile submarine. Source: NARA Still Pictures, College Park, MD.

So this was not an ideal boat by any means — in a war situation, it would need to surface, ready the missile to launch (in whatever conditions the sea was giving it), and then during the entire period that the sub-sonic missile made its way to its target it would be effectively broadcasting its position to whomever happened to be listening. And here’s a real bonus: if a Soviet plane or boat happened to destroy the Growler while the missile was in flight, they would be effectively disabling the missile. So unsurprisingly many on the Growler saw the use of their most potent weapon as a sort of personal suicide pact — perhaps an apt metaphor for the nuclear age in general.

Given these limitations, and the fact that the Grayback class was phased out in favor of the much more useful Polaris submarines (which were nuclear powered, and could fire ballistic missiles while submerged), it’s easy to ignore them. But as historians of technology often emphasize, we often learn as much from “failed” technologies as we do from “successful” ones. The Grayback class of submarines were seen as temporary. They were the US Navy’s first real foray into an underwater nuclear capability, designed to be fielded fast. The sub and the missile both reflect this expediency to their core.

The exhibit works to both explain the development and capabilities of the submarine and the missile, but also to contextualize them within the broader context of the early Cold War. Anyone who attends the exhibit ought to see my intellectual fingerprints all over it: it is an exhibit about the inseparability of technical developments and their political and historical contexts.

Regulus missile profile, July 1957. The censored word (the little line of dots) is “Atomic,” as a differently-redacted version indicates. This was when it was planned to use the W-5 warhead; the missile was later modified to carry the thermonuclear W-27 warhead. Source: Office of the Secretary of Defense, “The Guided Missile Program” (July 1957), Eisenhower Library, copy from GaleNet Declassified Documents Reference System.

The Intrepid Museum has a great team of exhibit curators and staff (a special shout out to my main collaborators Elaine Charnov, Jessica Williams, Chris Malanson, Kyle Shepard, and Gerrie Bay Hall). And, an aside, their offices are inside the aircraft carrier, deep within the steel hallways that are inaccessible to the public. Which makes sense in retrospect (museum space is always limited, so of course the offices would be kept within the cavernous carrier), but hadn’t occurred to me prior to seeing them. It’s a pretty unusual work environment from a physical standpoint — steep stairs, enough steel to kill your cell reception completely, unlabeled and winding passages, and very unusual acoustics as noises move through the entire hull.) In my usual job, I’m not usually a worker on large teams (e.g., more than three or four people); for a museum of the size of the Intrepid, there were maybe half a dozen people I regularly talked with, and another half a dozen more who I occasionally intersected with.

My job was to help with the broader conceptualization, aiding with the overall research (including a trip to NARA to digitize the Growler’s “muster rolls,” giving us a record of nearly everyone who served on the ship), much of the exhibit text (which of course had to be carved down quite a bit from my word-count-busting original drafts), and aiding in the choosing and creating of the visualizations. I also put them in touch with my colleagues at the Stevens SCENE Lab, who developed some pretty interesting audio-haptic interactives for the exhibit, including a virtual sonar station and a magical vibrating box that gives you a sense of what it would have sounded and felt like to be on an operating submarine. We wanted to make sure that people who couldn’t or didn’t want to go on board the submarine itself could get some sort of sense of its lived experience from the exhibit (the submarine is understandably somewhat cramped and features tiny hatches every so many feet, so people with mobility issues may not be able to go aboard it).

More generally, in the exhibit we tried to situate Growler within a broader past (going back to the developments of atomic bombs, cruise missiles, and modern submarines in World War II), but also its future (the creation and evolution of the nuclear triad). It is an exhibit that tries to do a lot of intellectual work (and if it gets reviewed as trying to do too much, well, you know who to blame) in a subtle way, painting a picture (one that the readership of my blog is probably more familiar with than the average person) of the kinds of forces and mindsets that were at work in the Cold War, and the way in which the politics, technology, and historical context mutually affected one another. There’s no simple good/bad message here; we’re hoping that visitors will leave with new questions about the history of nuclear weapons and the Cold War lodged in their heads.

Malformed muster roll for the USS Growler from 1963, courtesy of NARA. Not much you can do with that other than admire its strange beauty.

I also adapted a version of the NUKEMAP for use on museum exhibit touch screens, which I’m pretty happy with — aside from the aesthetics of it, which I think look pretty good, and some clever technical bits (it has some nice features to try and mitigate loss of connectivity issues that will inevitably come up), I’m especially pleased that from the very beginning the museum has been onboard with making sure that we talk about what the physical and human consequences of using the Regulus missile would have been. It would have been an easy thing to gloss over (because it can make people uncomfortable), but everyone agreed that you really couldn’t talk about this technology honestly without talking about what it would actually do if it was used.1

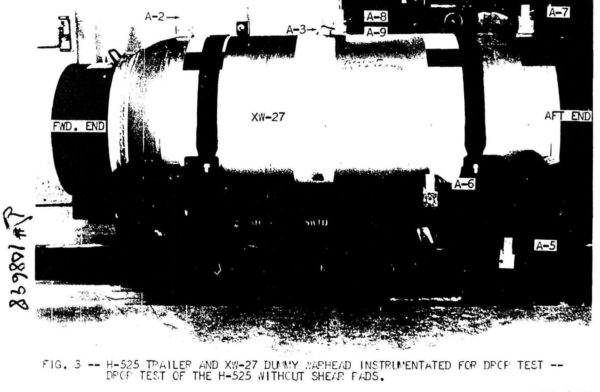

From a research perspective, the most rewarding thing was finally, after a lot of searching, finding a photograph that gave me an idea of what the W-27 warhead looked like. Warhead shapes can tend to be kept pretty close by the government, because they are frequently revealing of the internal mechanisms, and the W-27 was especially tricky because it was produced in unusually limited numbers. It was a “conversion kit” for the B-27 nuclear bomb, used only on the Regulus in the end, and so only 20 of them were ever produced. The breakthrough was realizing that there are many reports produced by Sandia National Laboratories that were investigating the structural integrity of not the warhead itself, but the carts and containers that would transport it. When they did these tests they would use a dummy warhead mockup that was the right shape and size of the warhead — thus providing far more pictures than I needed in the end. In the end, like most secrets, the warhead’s shape is mostly uninteresting on its own terms (it looks like a thermos with a firing unit bolted to the end of it), but there’s something so satisfying in being able to see it, and more or less figure out how it probably fit inside the Regulus.

A “dummy warhead” of the W-27, which gives one a pretty good idea of what it looked like. I suspect the electronics and arming unit are contained in the part labeled “FWD. END” here. Source: “Drop Test of the H-525 Without Shear Pads,” Sandia National Laboratories (July 1958).

As a collaboration, I thought it was extremely fruitful, and it was an interesting and exciting challenge to see how I would translate my broader interests in the history of nuclear weapons and the Cold War and turn them into something that would be accessible and intellectually stimulating to the general audience museum crowd.

The exhibit will be running for at least the next year, but is slated to be more or less permanent (things get complicated for long-term planning when your exhibit is on a building on top of a New York City pier, I have gathered), so if you’re in Manhattan, please feel free to stop by and take a look. It’s not just a first-generation nuclear-armed submarine that you can walk through, it’s also a deep dive (pun intended) into the Cold War context that led to the creation and use of such a weapon, and a meditation on the peril and value of imperfect solutions.

- If you work in a museum and think a NUKEMAP interactive would be useful, get in touch. The new “NUKEMAP Museum” framework is pretty flexible and could be adapted to a lot of different exhibits. [↩]

While the success of Polaris really put the nail in the coffin, there were safety concerns over the hangars too… They represented a huge floodable volume in a particularly inconvenient/hazardous location. (In the bows for the first generation of SSG/SSGN, midships and well above the CG in the unbuilt second generation.)

It’s also worth noting that Regulus-I was akin to Polaris A-1/2, a stopgap weapon while the next generation matured. (This was pretty common across the board in the 1950’s.) The indiscretion problem caused by the TROUNCE active guidance system would (would have) gone away as the Regulus-II had an inertial guidance system.

As a SSBN missile fire control tech, I was very pleased when they decided the Regulus crews would get patrol pins too. They certainly deserved them, and the crews of the SSG’s even more so. Service on the converted Fleet boats (both the missile carriers and the mid-course guidance boats) was reputed to be particularly unpleasant as they were all starting to show their age.

The Air and Space Museum Annex in DC has a Regulus, always looked so classic 1950’s tech to me

https://flickr.com/photos/28685581@N06/sets/72157631351011338

Will this be a long running exhibition?

At least five years, I have heard.