To round off this week of centrifuges, I thought we might actually look at a few of them. Photographs of real-life enrichment technologies are not too common. You can find quite a number of pictures floating around of Calutron (electromagnetic enrichment) technology from World War II, but that’s because the United States decided pretty early on that Calutrons weren’t too sensitive. (Rightly or wrongly; just because they are inefficient doesn’t mean they don’t work. Iraq famously pursued Calutron technology during its pre-1991 nuclear program; the major technical snag seemed to be that somebody bombed the facilities.)

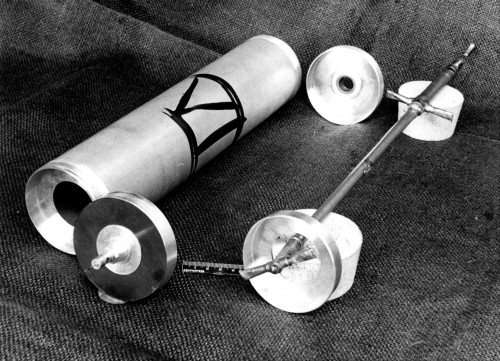

But gaseous diffusion? Laser enrichment? Aerodynamic enrichment? Not so much, beyond photographs of BIG buildings or very schematic conceptual diagrams. With centrifuges, though, there are some images from a variety of time periods and sources. As I mentioned on Monday, you can find some pretty nifty Zippe-type centrifuge photographs in old research reports from the 1950s that the Department of Energy still hosts pretty accessibly. These are kind of amazing, given how they more or less disassemble the devices in what looks like a pretty helpful fashion.

…and so on with the “powdered magnetic core, completed stator, and driven end of rotor showing steel plate and supporting needle,” and “upper magnetic bearing, rotor, and top of scoop assembly,” and even a nice little one of the rotors mounted up for stress testing. Interesting that these things are out there — especially when the CIA apparently decided, in 2003, that showing rotors of pre-1991 Iraqi centrifuges was too sensitive to put up on the web (after they had already put them up for awhile).

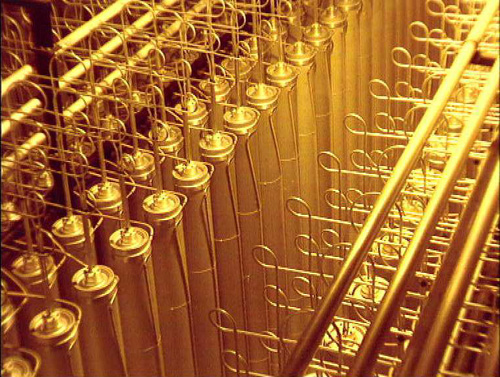

There are a few photos of URENCO centrifuge plants from Europe, but not as many as you’d think from a venture whose corporate slogan is “enriching the future.” I’m partial to this gold-tinted one that’s been floating around the web for awhile; it looks like Scrooge McDuck was the contractor (but I’m pretty sure it’s just the lighting — other images I’ve seen show them to be silvery):

It’s hard to get a sense of scale from cascade photos like this, though.

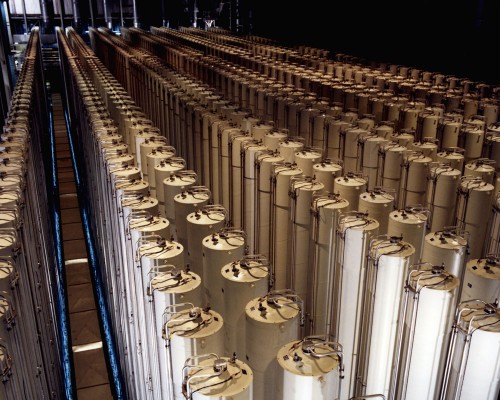

In the early 1980s, the United States’ DOE built a prototype centrifuge plant at Piketon, Ohio, but abandoned it by 1985. Much more recently (the 2000s) the private United States Enrichment Corporation took over the site and has been building a demonstration plant on it. What’s interesting about these centrifuges is that they are of a different model than the previous ones; the “American centrifuge” is a colossally large design. (The fact that they have to label them as “American” is a nice reflection of the fact mentioned on Monday that the US lost its initiative in developing centrifuges. We don’t have the “American” gaseous diffusion method or the “American” electromagnetic method.)

The 1980s Piketon photos are pretty impressive. These are from the DOE Digital Archive:

The last one really gives you the sense of scale with those suckers — they are huge!

The current Piketon plant looks pretty similar. USEC has a few photos on their own website:

I find these less inspiring, photographically, than the ones from the 1980s, but they look like the same centrifuges. The length here — some 12 meters long — is functional, and not just an example of the Supersize-Me American culture. The “American centrifuge” is much more efficient than the other models currently being used, apparently.

Now, all of the above is sort of interesting, but is just something of a prelude for the next batch of photos. In April 2008, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad made an official visit to the Natanz site, one of Iran’s controversial centrifuge facilities. Surprisingly, his office took several dozen photos of the visit and posted them on the official Presidential website. These have been a goldmine for wonky types wanting to understand Iran’s centrifuge developments, and have, of course, served as the illustrations for half a million articles about Iran and the bomb since then. A few of my favorites:

The last one I like because of a small, easy-to-miss detail: you can see one of the blue IAEA safeguard cameras above Ahmadinejad’s head. The blue box is a sealed case inside which the video camera is locked, and the closed-circuit camera feed is beamed back to IAEA headquarters in real-time (so I gather). (A correspondent e-mailed to say that at the plant in question, a pilot plant, the cameras aren’t real-time — they just stored the footage for the IAEA to pick up, which is every other week or so. I thought I had heard somewhere that they were real-time, but I can’t remember where. They do have real-time monitoring in their plants that can do up to 20% enrichment, though.)

Given how relatively few photos there are of centrifuges floating around, why did Iran post so many on its Presidential website? I think the message is pretty clear, personally: they are trying to demonstrate a lack of anything to hide. If the centrifuge program isn’t “secret,” then it isn’t scary, right?

Of course, the obvious rejoinder to this is that they are of course being selective about what they show. Such is the nature of any kind of publicity like this. You show a little, to show that you aren’t secretive, but of course, you do hold things back. Whether that holding back violates the NPT or the Additional Protocol and so forth is a question for another day. But I’m always fascinated by the theatre of “transparency,” which has — since the early days of the bomb — been part of maintaining nuclear secrecy. Secrecy has never just been about holding things back: it has always been a game of simultaneously withholding and releasing, of giving a little so you can hold back a lot.

How do we distinguish between genuine transparency and transparency in the name of secrecy? That’s the $64,000 question, isn’t it? Because when you get it wrong, you get a situation like Iraq: trying to prove a negative (that they didn’t have active WMD programs hidden away) turned out to be an impossible job (not because it is inherently impossible, but because of the various political and organizational forces stacked against the attempt). One can distinguish between the two in retrospect — once you’ve actually dismantled the country and its programs and whatnot — but that’s disturbingly too late.

To be fair to the Iranians, that’s what they said in 2008 when the pictures were taken (we have nothing to hide). Plus the six party talks were showing some signs of life before collapsing again.

One cannot help but wonder what the future holds with the recent apparent success of parahydrogen raman downconverted carbon dioxide radiation for selective excitation of 235UF6 ro-vibrational modes. eg. the SILEX process. It’s successful enough that an enrichment plant would need only a fifth as much space as a Zippe gallery, apparently. It’s slightly unnerving.

Regarding transparency versus secrecy: there is a third way, viz. strategic ambiguity.

To a large degree, the nuclear programs of Israel, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iraq, and Iran can and/or could be characterized by a doctrine of strategic ambiguity. The doctrine of strategic ambiguity correlates with nationalism and essentially localized political conflicts: for example, it is the extension of deterrence to the RoK by the US that leads the DPRK to threaten the US—not the other way around. Strategic ambiguity goes hand in hand with the economic incentive to keep any deterrent as small as possible, rather than to establish “parity”. So we can expect to see more of this in the future. Iran is just a case in point. Iraq is another, and strategic ambiguity cost Saddam Hussein everything.

I’m not sure where the Iranian regime comes out on the cost-benefit calculation.

Incidentally, I believe a case can be made that the second Iraq war was taken as a preemptive action betraying a lack of faith in traditional nuclear deterrence in the face of strategic ambiguity (you can’t really communicate nuclear doctrine without some clarity on weapons and delivery systems), and also as a demonstration intended to bolster (conventional and nuclear) forward deterrence and counterproliferation towards nation-states which might sponsor terrorism. In short, it was a last-ditch attempt to keep the rules like they were.