Today is the one-year anniversary of the Hawaii false alarm, in which the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA) sent out a text alert to thousands of Americans in the Hawaiian islands that told them that a ballistic missile was incoming, that they should take shelter, and that “THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

I’ve spent the last few days in Hawaii, as part of a workshop hosted by Atomic Reporters and the Stanley Foundation, and sponsored by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, that brought together a few experts (I was one of those) with a large number of journalists (“old” and “new” media alike) to talk about the false alarm and its lessons.

You’re looking at the photo documenting the only beach time I got while in Hawaii. Seriously. Thanks to Andrew Futter for taking this picture. You should check out his book, Hacking the Bomb: Cyber Threats and Nuclear Weapons (Georgetown University Press, 2018). I enjoyed getting to spend a few days hanging out with him.

Given that it is supposed to be snowing back home, you’d think a trip to Hawaii would come as a very welcome thing for me, but almost all of my time was spent in windowless rooms, and an eleven-hour flight is no picnic.1 So I spent some time wondering, “why have this workshop here?” I mean, obviously the location is relevant, but practically, what would be different if we had held the same meeting in, say, Los Angeles, or Palo Alto?

Over the days, the answer became very clear. When you are in Hawaii, everyone has a story about their experience of the false alarm. And they’re all different, and they’re all fascinating. On “the mainland,” as they call us, we got only a very small sampling of experiences from those here in Hawaii, often either put together by people who were interested in being very publicly thoughtful about their feelings (like Cynthia Lazaroff, who we heard a talk from, who wrote up her experience for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists), or the kind-of-absurd responses that were used as examples for how ridiculous the whole thing was (e.g., the guy who was trying to put his kids down a manhole). Out here, though, every taxi or Lyft driver has their own experience, along with everyone else.

A few of the responses, broadly paraphrased by me (I didn’t record them, and this is not systematic), follow. It is worth remembering that these are coming a year later, and one would expect their memories to be significantly altered by the passage of time, the increased knowledge about what happened, and, of course, the knowledge that, while “NOT A DRILL,” it was a false alarm.

“I didn’t think it was real. I thought, if it was a real thing, they would also sound the sirens.”

This was from a Lyft driver, who looked like she was in her twenties. Hawaii has an extensive emergency management infrastructure for tsunamis. While I went for a long walk early one morning, I passed by one of the sirens for this, and noticed that they still use the same Civil Defense imagery from the 1950s on their equipment. The people of Hawaii know these sirens well, because they test them on the first day of every month. So the Lyft driver’s response was very interesting to me in this respect: she had expectations about what a “real” emergency would be like, and the ballistic missile alert didn’t meet them.

“I follow the North Korea situation closely, so I assumed it had to be false, because I am sure they wouldn’t just launch a missile like that, because it would be suicidal.”

This is a response that one journalist, and one policy analyst, both independently gave, almost word for word. In this example, people who felt they were connected to the broader context of the US-North Korea situation, and felt they understood North Korea’s strategic aims and options, reasoned that an actual attack from North Korea was unlikely, and thus discounted the alert.

The reasoning behind these “discounting” stories, I might suggest, is terrible. To assume an alert is false because it does not meet your expectations is completely silly unless you are much better informed about what a real alert would look like than our Lyft driver apparently was. Is the ballistic missile system and the tsunami system the same one? Would they use the tsunami alert for a missile alert? Could one system be active and the other sabotaged, malfunctioning, or otherwise not activated? These are big questions! In a real emergency it is not worth betting your life that things aren’t working the way you’d expect them to.

And the “context” justification for not believing it is hubris itself. We only see a portion of the total “context” at any one point. Who knows what has happened on the Korean peninsula several hours ago, but hasn’t made it to your ears? If you’re in Pacific Command (or can contact someone there), sure, you might know enough context to discount such an alert. Otherwise, it’s foolish to do so.

The fallacy of both of these reasons for discounting the alert, as an aside, was made very clear when I visited the Pearl Harbor Memorial. Conventional wisdom prior to Pearl Harbor was that Japan did not pose a major threat to the US, and would not dare to attack such a country.2 A “war scare” with Japan and the US had risen up and dissipated a few months before the actual attack, leading many to think the threat had passed, and even on the day of the attack, many soldiers and radar operators on Hawaii discounted what their own eyes saw because they thought it must be some kind of exercise, giving up any possibility of defense prior to the main attack.

One of the local journalists we talked to had more plausible means to discount the alert as false: he could contact a high-enough ranking member of the Hawaii government. That’s not a bad reason to discount it (though even then, would you bet your life on this official being “in the loop?”), and much of our discussions as a group centered around what the role of journalists ought to be in such a crisis situation, if they had information that was not yet released officially.

“I figured it was probably false, but I went into my bathtub anyway. If I were doing it again, I’d have brought a few beers to pass the time.”

I heard a few people say they understood the “take shelter” message to mean that they should get into their bathtub. I’m not sure where they got that — perhaps the television? I am not sure a bathtub is the best place to be; usually the emergency advice regarding bathtubs is to fill them up with water, so that you have several gallons of potable water in case there is a disruption of service. But anyway, as silly as this story sounds, the guy (a staff member) more or less did the right thing: wasn’t sure if it was real, but treated it as if it was. (And the beer thing is a good joke until you remember that beer is actually a valid post-nuclear water source!)

“I woke up too late, and I only saw the retraction.”

I liked this one, only because it highlights that an early-morning alert is only going to reach so many people.

“I was sitting in my kitchen, and I had finished a cup of coffee. I thought, ‘I should not have more coffee.’ But then I saw the alert, and I thought, ‘I can have one more cup of coffee.’ So I sat and drank my coffee. I thought it was real! But I am 70. I was OK with it. But my relatives on the mainland called me, to say goodbye. They were crying. But I was OK. Of course I believed it was real — it was on the TV!”

This was my Japanese-American (emigrated here in the 1970s from Tokyo) taxi driver who took me to the airport. I don’t have anything clever to say about his story, but I loved it so much. One more cup of coffee, if that’s what it’s going to be.

The other extremely useful thing about being out here was talking to local journalists. It’s easy to dismiss local journalism — a lot of it is pretty bad, and the consolidation of news sources has made a lot of it less “local” than it used to be. But the ones I met here knew a hell of a lot more about this story than most of the national news sources I read. Eliza Larson, of KITV, was part of the conference the entire time, and her knowledge and perspective were crucial. We also visited the office of Honolulu Civil Beat, and they were also great. (And one of them, not knowing my relation to it, described the NUKEMAP as an “authoritative tool” that they found very useful, which of course I delighted in.)

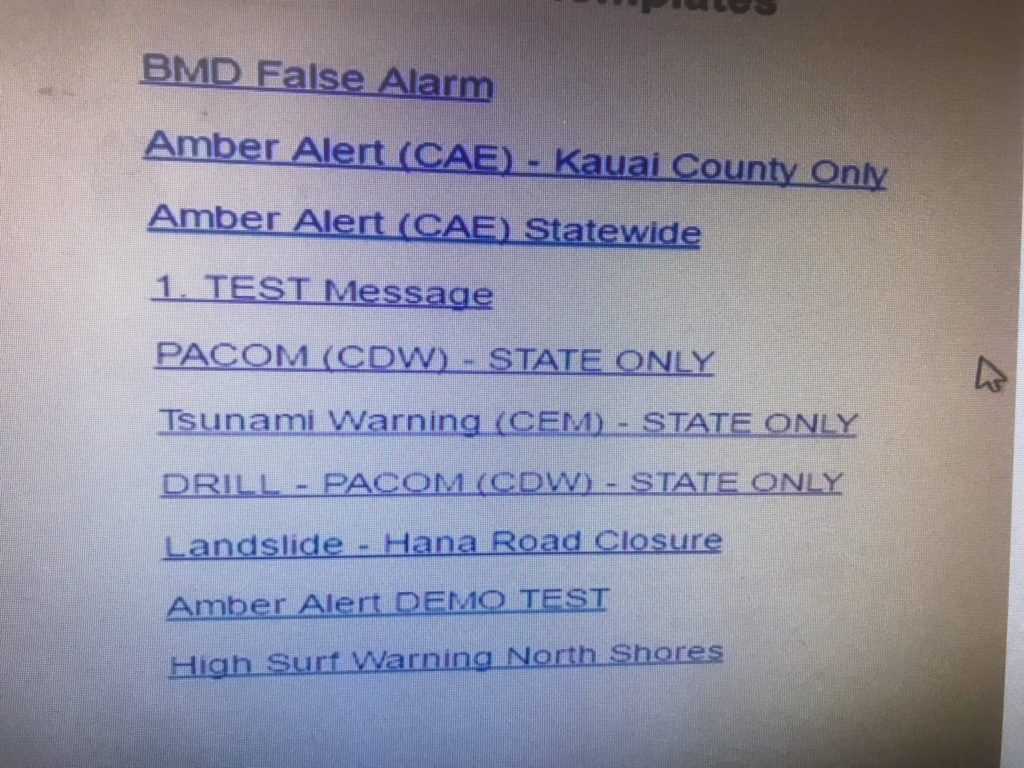

The alert system used by HI-EMA, per Honolulu Civil Beat. It’s a bad interface, no matter how you slice it. The first option, “BMD False Alarm,” was added after the false alarm incident.

One thing that emerged for me is that the narrative of “what went wrong” is still not quite known. The first draft of the story, which most people believe, is that an employee clicked the wrong button on the alert website. This is absurd enough to be believable, and the “lesson” of it is clear: user interfaces matter, a conclusion that resonated very strongly with the “human factors engineering” analysis that became very popular following its application in the post-mortem of the Three Mile Island accident.

But that turns out not to be what happened, as emerged later. Two different versions have been put out. The “button pusher,” we’ll call him, later told journalists that he, in fact, had not done it accidentally, but that he had been told it was real and he believed it was real. Which turns it into a very different sort story: one about miscommunication, human error, and a system problem that makes it very easy for an alert to be sent (by a single person), but not to be rescinded.

The other later version, put out by HI-EMA officials, is that the aforementioned “button pusher” was in fact an unreliable, unstable person who had displayed personality problems in the past and totally “shut down” after sending the alert. The “button pusher” disputes this version of events quite vigorously, we were told, and no documentation has been provided by HI-EMA to substantiate this account. If this version is true, the story is about human reliability, along with the aforementioned system problem. (The “button pusher” was fired from HI-EMA shortly after, and was the target of considerable ire by an understandably furious public.)

Both HI-EMA and the “button pusher” have self-interested reasons for preferring their versions of the story, as it shifts the blame considerably. Either way, the system failures remain: a single individual, whether by confusion or by malice, should not be able to send out a false alarm by themselves to thousands of people.3

The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA) emblem. Tell me this isn’t the most amazing piece of graphic design ever. Civil Defense! Volcano! Tsunami! Hurricane! SHARK TEETH!

The grim irony is that Hawaii was being extremely proactive when it came to the possibility of a ballistic missile threat. They’re not wrong to think that it should be in their conception of the possible risks against them. They appear to have been one of the only statewide emergency management agencies that had worked to reintroduce nuclear weapons threats into their standard alert procedures and drills.4 They set up a system that, by any measure, contained terrible flaws, ones that any outside analyst could have seen.

And we were told that a consequence of this false alarm, aside from the panic, fear, and confusion (of such magnitude that may have caused at least one heart attack), we were told, is that Hawaii seems to have put its ballistic missile alert system on an indefinite hold. Which is understandable, but unfortunate. Because the nuclear threat, including the ballistic missile threat, is still a real one. It will continue to be a real one as long as there are hostile states with nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles — which seems like it might be a very long time indeed. HI-EMA was right, I think, in making ballistic missile threats part of their “threat matrix” of possibilities that they, as the organization tasked with preserving the lives of their citizens, were tasked with addressing. But they also had a responsibility to set up a system in which false positives would be very unlikely, and they utterly failed at that. The consequence is that not only are the residents of Hawaii less prepared than they had previously been for the possibility of a nuclear attack (which if you think is so remote a risk, read Jeffrey Lewis’s novel, the The 2020 Report, and get back to me), but other state governments are probably going to continue to be shy about taking nuclear risks seriously, for fear of the terrible publicity that comes with getting it wrong.

Dispatched from a mai tai bar at the Honolulu airport, waiting for a red-eye flight. Please chalk up any typos to the mai tai. Expect blog posts somewhat more regularly in 2019.

- Though the flight was pretty good, to be honest. The agency that had set up my ticket had booked me in practically the last seat on the plane, and I was not looking forward to that. But for whatever reason, when I went to check in and get my boarding pass the night before, I was offered a chance to upgrade to first class for only $299. Which is pretty amazing in any circumstances, but for an eleven-hour flight it felt foolish to pass it up. And so I didn’t, and had a very nice flight. The real perk of first class not the better food and nicer flight attendants — though those were nice — but was the fact that my seat turned into a totally flat bed. That was pretty amazing, and my first time being able to experience that on a plane. It makes a huge difference. [↩]

- Among its many materials, the exhibit prominently featured a racist editorial cartoon by Theodor Geisel — Dr. Seuss — that ridiculed the notion of a Japanese attack. UCSD has a nice collection of his wartime cartoons, and I was particularly struck that he published many on the theme of how unlikely an attack was, with the last published only two days before the surprise attack. [↩]

- As an aside, I have not been able to figure out what order of magnitude of people receive the alert. “Thousands” is conservative. People on islands 100 miles away from Oahu got the alert as well. A Congressional Research Service backgrounder on the incident says that HI-EMA attempted to stop transmission within minutes, so it may not have reached the full intended audience. Some people said that their phone got the alert, but their spouses’ phone did not. “Tens of thousands” is probably conservative. “Hundreds of thousands,” upward to a million, might be a possibility, but I don’t know. [↩]

- I took a tour of the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency not long after the alert, and was told by the head of the organization that they did not have any plans whatsoever in place for a nuclear weapon detonation, much less a ballistic missile attack. This was kind of amazing to hear, especially since MEMA is located in an underground bunker constructed in the 1960s to survive a nuclear attack. [↩]

Hi there!

I love your blog and I love your content, glad to see you posted again.

I’m a user from EU, and I’m worried about the nuclear problem globally. Reading this extract:

“Because the nuclear threat, including the ballistic missile threat, is still a real one. It will continue to be a real one as long as there are hostile states with nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles”

makes me wonder what are your opinions regarding Non-Proliferation Treaty (I guess you posted a lot in connection with it). Reading hostile states makes me ask you, don’t you think that the threat will continue to be a real one as long as there are states with nukes? I’m not sure if I express my point properly.

Thanks

PS. Sorry for my english, is not my native language

Yeah, I put “hostile” there mostly just to deflect the broader “should there be nukes at all question.” Which is an important one. The tricky thing is that if you go in that direction with the conversation, pretty soon you get two sides that won’t talk to each other — the nuclear abolitionists versus the various flavors of people who think nuclear weapons need to be, or at least will be, part of the world for the foreseeable future. My hope in these conversations is to talk about this issue in a way that doesn’t just turn it into a proxy for this other discussion. But the fact that it touches on it is unavoidable, and you noticed one of my little attempts to smooth that over. 🙂

Thanks for the post Alex, this false alarm still reverberates within the Emergency Management community, particularly here in California where we had our own problems in the past few years with public warnings for quick-moving wildfires.

Lots of work to do on public information for a potential nuclear detonation in the U.S., whether ballistic missile-borne or terror related. We still seem to be firmly planted with our heads in the sand. BTW, I use NUKEMAP for presentations all the time, nothing else gets the information across better!

Best Regards,

Jim Acosta (not the CNN reporter!)

Certified Emergency Manager

Los Angeles, California

“the system failures remain: a single individual, whether by confusion or by malice, should not be able to send out a false alarm by themselves to thousands of people.” No doubt you see the analogy to “a single individual (e.g., a President), whether by confusion or by malice, should not be able to order a nuclear attack upon millions of people.”

Complacency about warnings is not just nuclear: My parents in 1960s California received a knock on the door warning of a tidal wave (tsunami). They did not pack up the kids and drive to higher ground. Fortunately for me, it was a false alarm.

> The reasoning behind these “discounting” stories, I might suggest, is terrible. To assume an alert is false because it does not meet your expectations is completely silly unless you are much better informed about what a real alert would look like than our Lyft driver apparently was.

Why is it silly though? The base rate on nuclear attacks is absurdly low. That makes it highly likely that the alert is a false alarm. If you have a cheap and high benefit option available to you, taking it makes sense. But if you can’t point at any option available to you which would significantly raise your odds of survival, you’re risking embarassment and discomfort for a very low expected return.

One of the tricky things in talking about nuclear risks is that if you evaluate them in a Bayesian way (“how often have they happened in the past”) then no, they don’t loom large. But if you evaluate them in a “how often have nuclear attack risks come dangerously high,” then the number becomes considerably higher.

Separately, in thinking about risk, the usual calculation is not simply the likelihood of it occurring. It is the likelihood multiplied by the consequences. In the case of nuclear risks, the likelihood might be very low indeed, but the consequences are extraordinarily high. So they deserve our attention.

Embarrassment in particular is a poor reason to discount thing that may be a threat to lives, in my opinion.

That’s why I brought up the availability of options. The expected benefit of taking a protective action is:

P(an attack is happening) * P(the protective action will save me) * (value of my life)

If I know of an effective way to protect myself, then it might be worth using even with a low probability of attack. But if all the protective measures I know of are bad (or I believe they are), then they probably won’t be worth trying unless I have a high confidence that an attack is happening.

To be more concrete. If my workplace had a room designated as safe in case of an attack and I received an alarm, I would probably go there. Even if I was quite sure that the alarm was a mistake. But as is, I’m not going to duck under my desk on the off-chance that it is helpful in the unlikely case of the alarm not being a mistake.

The alert was an official, state-sent emergency message that said there was an incoming ballistic missile. The advise was to take shelter: find a place indoors, preferably the center of the building, ideally a basement. There are tangible benefits in terms of preventable casualties from both blast and radiation if people did such a thing. Your argument is essentially, I would ignore that, because you think the odds of the emergency message being valid is low (despite your being totally ignorant of, say, what might have happened in the last 2 hours in North Korea), and that you would be embarrassed to take shelter if it turned out to be a false alarm.

I hope you can see this is not a very strong good argument.

Separately, if I can share a little bit of lived wisdom: Don’t worry so much about being embarrassed. Life is a lot more enjoyable that way.

I was on Maui the morning of the false alarm. (My biases are: I grew up in the ’50s ducking and covering under the desk facing away from the windows and I survived rocket attacks in Viet Nam where the sirens came after the first rockets had already impacted.)

When the first alerts appeared on TV, the local newsreaders said something like they didn’t know what was going on but they were going to get to the bottom of it, imparting the attitude that they did not take it seriously. Some of our group’s cell phones (with California area codes) received text alerts and some did not. Looking out our room’s window I saw few people rushing back into the building, not much unusual activity. Then I decided to move away from the windows and go to the stairwell as advised by the hotel’s P.A. announcements. We were updated by the hotel regularly but it was basically paraphrasing the TV reporting. Standing in the stairwell lost its entertainment value pretty quickly and I started wondering if DPRK would launch a self-destructive attack if they had never tested a “special” weapon loaded onto a rocket (as far as I knew). I decided a real attack was on a very low order of probability. Perhaps DPRK had fired off another test, but that was it. That afternoon, before sunset, I saw T-shirts for sale in Lahaina with the alert text message and “Just Kidding” at the bottom. The next day we encountered a shopkeeper who was still excited to the extent of seeming aroused by discussing the event, when we were not. She shared that she grew up in Israel and shelters were part of everyday life. She didn’t understand why Maui didn’t have shelters on every block. She said she wanted to dig a shelter on her property but the state or county would not let her. She asked if Oprah can have a bomb shelter up at her ranch, why couldn’t she have one at her cottage.