This month marked the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the cessation of hostilities in World War II. Anniversaries are interesting times to test the cultural waters, to see how events get remembered and talked about. I was exceptionally busy this summer, doing my part to try to participate in the discourse about these events. In case you missed them and wished you had not, here are a few of my appearances:

- “Why did the US choose Hiroshima?” (NPR’s Morning Edition) — on target selection, and what the scientists thought Hiroshima might mean

- “Five ways that nuclear weapons could still be used” (The Guardian) — an article I was asked to write, in which I attempted to avoid being both alarmist and smug

- “What it would look like if the Hiroshima bomb hit your city” (Washington Post) — an article about the NUKEMAP

- “How the Hiroshima bombing is taught around the world” (Washington Post) — an article about public perceptions of the bombing

- “The man who saved Kyoto from the atomic bomb” (BBC World News) — an article about Stimson and the decision not to bomb Kyoto

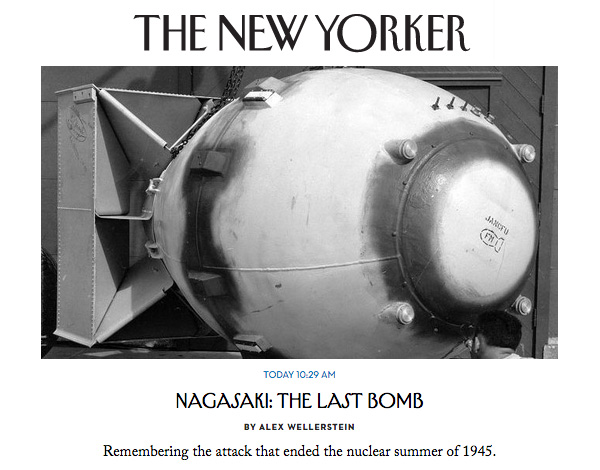

I also published a second blog post with the New Yorker on the often-overlooked second use of the atomic bomb: “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb.” I am proud of it as a piece of writing, as I was really trying to pull off something deliberate and subtle with it, and feel that I somewhat accomplished that.

On this latter piece, I would also like to say that very little of what I wrote would come as a surprise to historians, though the particular arrangement of Nagasaki-as-JANCFU (that is, with an emphasis on the less-than-textbook aspects of the operation, as a herald of the later chaotic possibilities of the nuclear age) is usually under-emphasized. We tend to lump Hiroshima and Nagasaki together when we talking about the atomic bombings during World War II, and I think they should probably be separated out a bit in terms of how we regard them. The first use of the bomb, at Hiroshima, was in many ways a very straightforward affair, both in terms of the strategic and ethical considerations, and the tactical operation. Whether one agrees with the strategic and ethical considerations is a separate matter, of course, but a lot of thought went into Hiroshima as a target, and into the first use of the bomb. Nagasaki, by contrast, was less straightforward on all counts — less thought-out, less justified, and was very nearly a tactical blunder. For me, it reflects on the very real dangers that can occur when human judgment gets mixed with the extremely high stakes that come with weapons as powerful as these. Any bomber crew can have a mishap of a mission, but when that mission is nuclear-armed, the potential consequences multiply.

The one notable exception to the “very little would come as a surprise to historians” bit in this piece is that Nagasaki was never put on the “reserved” list. For whatever reason, the idea that both Hiroshima and Nagasaki were “reserved” from conventional bombing is very commonly repeated, but it is just not true. The final “reserved” list contained only Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. Aside from the fact that no documentation exists of Nagasaki being put on the list (whereas we do have such documentation for the others), we also have the documentation actively rescinding the “reserved” status for Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata, so that they could become formal atomic targets.

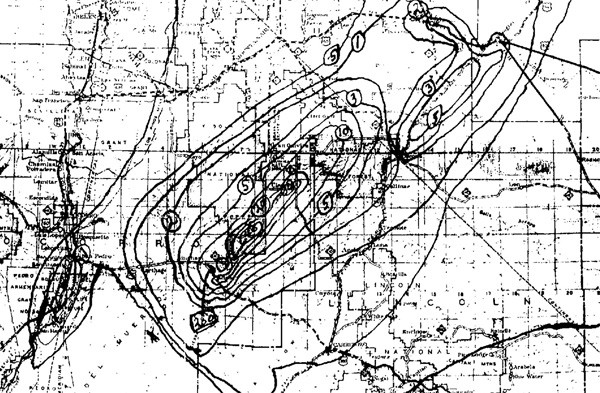

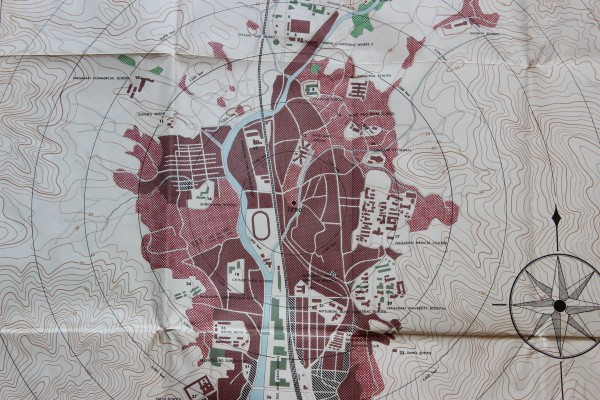

Detail from a damage map of Nagasaki, produced by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, 1946. I have the original of this in my possession. I find this particular piece of the map quite valuable to examine up close — one gets a sense of the nature of the area around “Ground Zero” very acutely when examining it. There were war plants to the north and south of the detonation point, but mostly the labeled structures are explicitly, painfully civilian (schools, hospitals, prisons). Click to enlarge. Here is a not-great photo of the whole map, to compare it with, and here is a detail of the legend. At some point, when finances allow, I will get this framed for my office, but it is quite large and not a cheap endeavor.

John Coster-Mullen’s book provided a lot of documents and details about the bombing run. One thing I appreciate about John is his dedication to documentation, even though his views on the meaning of the history are not always the same as mine. I thoroughly believe that rational people can look at the same facts and come up with different narratives and interpretations — the trick, of course, is to make sure you are at least getting the facts right.

It would be interesting at some point for someone to do a scholarly analysis of the popular discourse surrounding each decade of anniversaries since the bombs were dropped. 1955 was a fairly raw time, right after McCarthyism had peaked and the hydrogen bomb had been developed. 1965 marked an outpouring of new books and revelations from those involved in the bomb project, enabled by new declassifications (allowed, in part, because of the fostering of a civilian nuclear industry) and the fact that some of the major participants (like Groves) were still alive. I have no distinct impressions of 1975 being a major anniversary year, but 1985 resulted in a lot of hand-wringing about the relationship between the birth of the nuclear age and the nuclear fears of the 1980s. 1995, of course, was the first post-Cold War anniversary and one of the “hottest” years of controversy, catalyzing around the Smithsonian’s Enola Gay exhibit controversy and the “culture wars” of the mid-Clinton administration. We are still dealing with the hyper-polarization of the narratives of the atomic bombings that became really prominent in the mid-1990s — where there were only two options available, an orthodox/reactionary view or a critical/revisionist view. The 2005 anniversary did not make a large impression on me at the time, and seemed muted in comparison with 1995 (perhaps a good thing), except for the fact that some very noteworthy scholarship made its appearance to coincide with it.

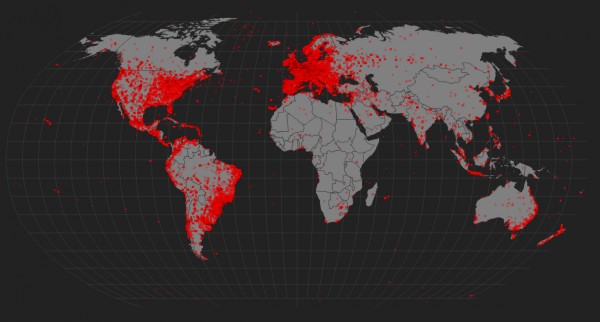

A small sampling of some of the international press coverage of the NUKEMAP around the Hiroshima anniversary.

And what of 2015? There were, of course, many stories about the bombings. Nagasaki got a better representation in the discourse than usual, in no small part because Susan Southard’s Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War received heavy promotion. (I have not read it yet.) The general discussion seemed less polarized than they have been, though I did see a fair share of hand-wringing and defending editorials pop up on my Google Alerts feed. I have speculated that I think anniversaries from this point forward will be somewhat more interesting and reflective than those in the recent past, in part because of the declining influence of American World War II veterans, who were such a strong force in the more recent ones. My (perhaps overly idealistic) hope is that our narratives of the bombings can settle into something more historically informed, more quietly reflective, and less keyed to contemporary politics than in the past.

For my part, I was impressed by the number of people online who were interested in re-creating Hiroshima on their hometowns. The featuring of NUKEMAP on the Washington Post’s Wonkblog drove an incredible amount of traffic to the site. It was one of those stories that could be essentially lifted and re-written to fit a wide variety of different cities or countries, and there were variations of the “What would happen if Hiroshima happened here?” written in dozens of languages over the days leading up to and beyond the anniversary. The result is that NUKEMAP’s traffic had an all-time high spike over 300,000 people on August 6. The traffic is a typical long-tail distribution, so in the week of August 5-12, there were well over 1 million pageviews for the NUKEMAP. There have been other spikes in the past, but none quite as big as this one.

Locations where the Little Boy bomb was “dropped,” August 5-12, 2015. These are unweighted (each dot represents an indeterminate number of detonations). Here is a heatmap (capped at 1,000 detonations — the actual cap is 28,116 — to make it easier to see the broader spread) showing where repeat detonations occurred. Here is a version where I have thrown out all locations where fewer than 10 detonations took place, and scaled their size and color by repetition. Total detonations is 266,483.

Where do people nuke, when they recreate Hiroshima? Well, all over the world, not surprisingly, though the biggest single draws are New York (which is a NUKEMAP default if it cannot figure out where you probably live) and Hiroshima itself (re-creating the actual bombing). I’ve exported the log data for people using the Little Boy bomb setting (15 kiloton airbursts) for the week of August 5-12, and the maps are shown and linked to above. Obviously it correlates very heavily with both population and Internet access, but still, it is interesting.

Lastly, a week after the anniversary, what more reflection is there to be had? A new poll came out in late July of a thousand Americans, asking them what they thought about the bombings. Overall, 46% of those polled thought that the dropping of the bombs on Japan was the “right decision” to do, while 29% thought it was the “wrong decision,” and 26% said they were “not sure.” Which one can interpret in a number of ways. The feelings appear to correlate directly with age — the older you are, the more likely you think it was “right,” and the younger, with “wrong.” It also correlates with a few other factors, notably political affiliation (Republicans strongly in favor, Democrats and Independents not so much), race/ethnicity, and income. I suspect all of these variables (age, political affiliation, race/ethnicity, and income) to be pretty highly correlated in general. Separately, the gender gap is pretty extreme — men defend the bombings by a very large margin compared to women.

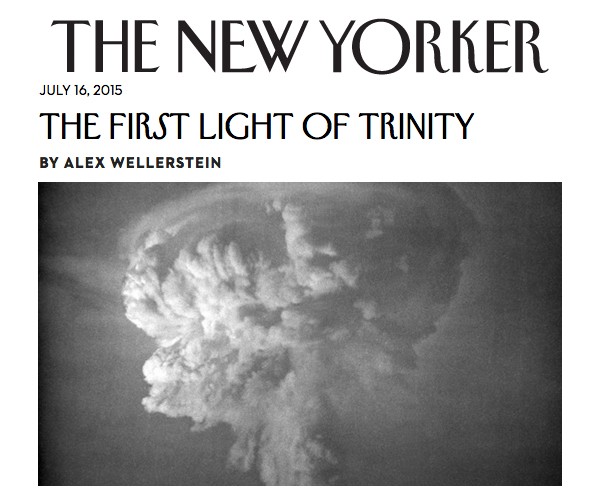

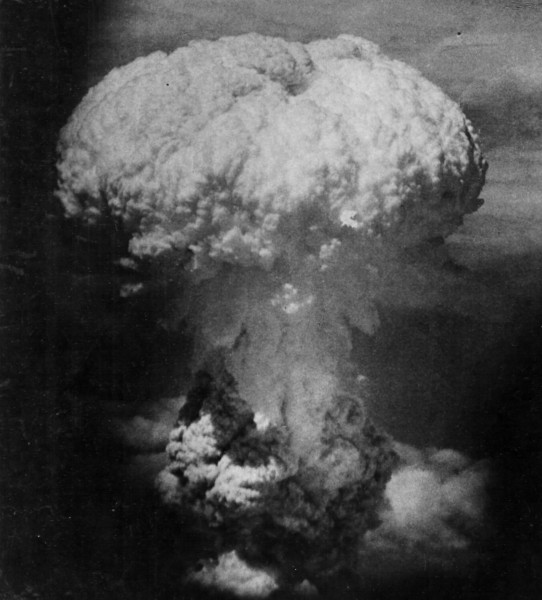

The head of the Nagasaki mushroom cloud — like a monstrous brain. Source: National Archives/Fold3.com.

None of this is extremely surprising, I don’t think. But I was taken aback by another question in the same poll, a strictly factual one: “Which country was the first country to build a nuclear weapon?” Only 57% of the total polled correctly identified the United States, and it gets very depressing when one looks at how this breaks down by age. Less than half of Americans under the age of 45 could correctly identify that their country was the first country to develop nuclear weapons. I don’t really mind if a lot of people can’t identify when the first weapons were used (another question in the poll); exact years can be hard for people, especially on the spot, and the differences between the options given were not so vast that they represent much, in my view. But 23% were “not sure” who made the first bomb, 15% thought it was the USSR, and 3% thought it was China! (Almost nobody, alas, thought it was France.) This is not a minor factual error — it is a fundamental lack of knowledge about the historical composition of the world. It reflects, I suspect, the waning attention given to nuclear issues in the post-Cold War.

One last reflection: How do I, a historian of these matters, find myself thinking about Hiroshima and Nagasaki these days? Increasingly I find myself uninterested in the question of whether they were “justified” or not, which contain so much predictable posturing, the same old arguments, with very few new facts or analyses. I think the bombings were a very muddy affair from an ethical, strategic, and historical perspective, and I don’t think they fit into any simplistic view of them. I’ve come to feel my position on these could be described as an “inverse moderate,” where a moderate seeks to make everyone feel comfortable, but my goal is to make everyone feel uncomfortable. If you think this history supports some easy, straightforward interpretation, you are probably throwing out a lot of the data and filling it in with what you’d like to believe. It is complex history; it does not boil down easily.

!["Komiya street (750 meters [from Ground Zero] before and after bombing. The archlike heavy lamp posts have fallen. One lies at the left of the lower photograph."](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Komiya-Street-600x186.jpg)

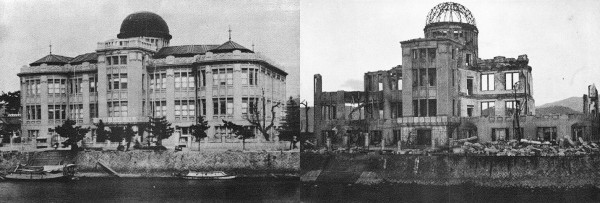

!["Prefectural Office (900 meters [from Ground Zero]) before and after the bombing. The wooden structure has collapsed and burned. Note displacement of the heavy granite blocks of the wall."](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Prefectural-Office-600x195.jpg)

![I find this one to be one of the most haunting — by filling in the missing structures, it contextualizes all of the "standard" Hiroshima photos of the rubble-filled wasteland. "Rear view of Geibi and Sumitomo Buildings before and after bombing. Taken from Fukuya Department Store (700 meters [from Ground Zero]) looking toward center. Complete destruction of wooden buildings by blast and fire. Concrete structures stand." In other places in the text, they usually point out that where you see a concrete structure like this, it has withstood the blast but was gutted by the fire.](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Geibi-and-Sumitomo-Buildings-600x205.jpg)