What was going through J. Robert Oppenheimer’s head when he saw the great fireball of the Trinity test looming above him? According to his brother, Frank, he only said, “it worked.” But most people know a more poetic account, one in which Oppenheimer says (or at least thinks) the following famous lines:

I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

This particular version, with a haggard Oppenheimer, was originally filmed for NBC’s 1965 The Decision to Drop the Bomb. I first saw it in Jon Else’s The Day After Trinity (1980), and thanks to YouTube it is now available pretty much anywhere at any time. There are other versions of the quote around — “shatterer of worlds” is a common variant — though it did not begin to circulate as part of Los Alamos lore until the late 1940s and especially the 1950s.

It’s a chilling delivery and an evocative quote. The problem is that most of the time when it is invoked, it is done purely for its evocativeness and without any understanding as to what it actually supposed to mean. That’s what I want to talk about: what was Oppenheimer trying to say, presuming he was not just trying to be gnomic? What was he actually alluding to in the Gita?

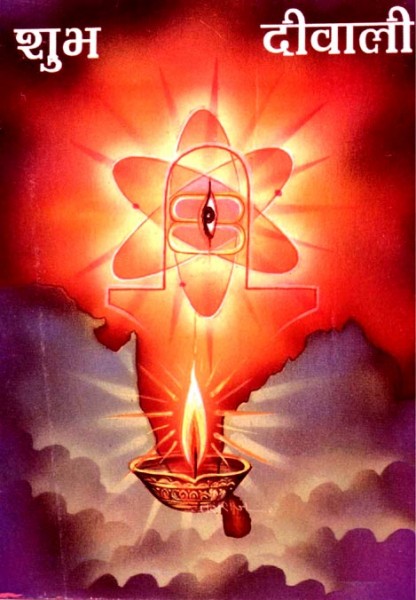

An Indian greeting card for Diwali from 1998, celebrating India’s nuclear tests. Source.

I should say first that I’m no scholar of Hindu theology. Fortunately, many years back, James A. Hijiya of the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth wrote a wonderful article on “The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer” that covers all of this topic as well as one might ever want it to be covered.1 Everything I know about the Gita comes from Hijiya’s article — so read it if you want much more discussion of this than I have here. I am particularly fond of Hijiya’s opening line, that Oppenheimer’s paraphrase of the Gita is “one of the most-cited and least-interpreted quotations” of the atomic age.

Oppenheimer was not a Hindu. He was not much of anything, religiously — he was born into a fairly secular Jewish family, embraced the Ethical Culture of Felix Adler, and saw philosophy as more of a boon to his soul than any particular creed. He enjoyed the ideas of the Gita, but he was not religious about it. Hijiya thinks, however, that much can be understood about Oppenheimer’s life through the lens of the Gita as a philosophical and moral code, something necessary in part because Oppenheimer rarely discussed his own internal motivations and feelings about making the bomb. It helps explain, Hijiya argues, that a man who could utter so many public statements about the “sin” and “terror” and “inhumanity” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could also have been the one who pushed for their use against Japan and who never, ever said that he actually regretted having built the bomb or recommending its use. It helps resolve one of the crucial contradictions, in other words, at the heart of the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

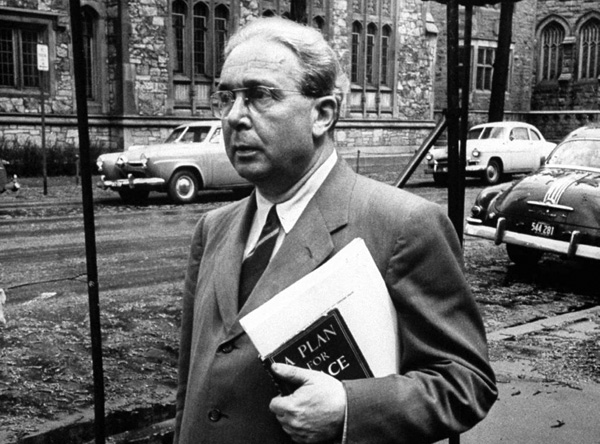

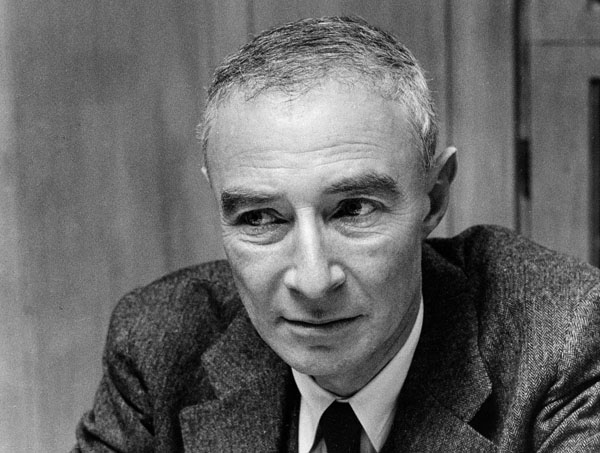

J. Robert Oppenheimer, from the Emilio Segrè Visual Archives.

It’s not clear when Oppenheimer was first exposed to the Gita. I have seen accounts, in oral histories, that suggested that he was spouting Gita lines even while he was a young graduate student studying in Europe. What is definitely known is that he didn’t start studying Sanskrit seriously until 1933, when he started studying with the renown Sanskrit scholar Arthur W. Ryder while he was a professor at Berkeley. In letters, he wrote gushingly about the book to his brother, and much later he quoted from it at the service held at Los Alamos in April 1945 upon the death of President Roosevelt.

The story of the Gita is that of Arjuna, a human prince who has been summoned to a war between princely cousins. Arjuna doesn’t want to fight — not because he lacks courage, or skill, but because it is a war of succession, so his enemies are his own cousins, his friends, his teachers. Arjuna does not want to kill them. He confides in his charioteer, who turns out to be the god Krishna2 in a human form. The text of the Gita is mostly Krishna telling Arjuna why Arjuna must go to war, even if Arjuna does not want to do it.

Krishna’s argument hinges on three points: 1. Arjuna is a soldier, and so it is his job — his duty — to wage war; 2. It is Krishna’s job, not Arjuna’s, to determine Arjuna’s fate; 3. Arjuna must ultimately have faith in Krishna if he is going to preserve his soul.

Arjuna eventually starts to become convinced. He asks Krishna if he will show him his godlike, multi-armed form. Krishna obliges, showing Arjuna an incredible sight:

Krishna revealing himself to Arjuna. Source.

A thousand simultaneous suns

Arising in the sky

Might equal that great radiance,

With that great glory vie.

Arjuna is awestruck and spellbound:

Amazement entered him; his hair

Rose up; he bowed his head;

He humbly lifted folded hands,

And worshipped God. . . .

And then, in his most amazing and terrible form, Krishna tells Arjuna what he, Krishna, is there to do:

Death am I, and my present task

Destruction.

Arjuna, suitably impressed and humbled, then agrees to join in the battle.

The above quotes are from Ryder’s translation of the Gita. You can see that Oppenheimer’s is not especially different from that, even if it is somewhat changed. Personally I find Ryder’s version of the last part more impressive — it is more poetic, more stark. Ryder’s translation, Hijiya explains, is a somewhat idiosyncratic but defensible one. What Ryder (and Oppenheimer) translate as “Death,” others have translated as “Time,” but Hijiya says that Ryder is not alone for calling attention to the fact that in this context the expanse of time was meant to be a deadly one.

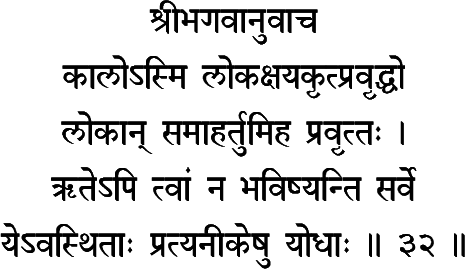

If you would like to see the famous “death” verse in the original, it is chapter 11, verse 32 of the Gita, and looks like this:

This website (from which I got the above) translates it as:

Lord Krsna said: I am terrible time the destroyer of all beings in all worlds, engaged to destroy all beings in this world; of those heroic soldiers presently situated in the opposing army, even without you none will be spared.

While I find Ryder’s more poignant, the longer translation makes it extremely clear what Krishna has in mind. All will perish, eventually. In war, many will perish whether you participate or not. For Oppenheimer and the bomb, this may have seemed especially true. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (and others on the target list) were on it not because they were necessarily the most important, but because they had so far been spared from firebombing. They were being actively preserved as atomic bomb targets. Had the bomb not been used or made, they probably would have been firebombed anyway. Even if the physicists had refused to make nuclear weapons, the death toll of World War II would hardly have been altered.

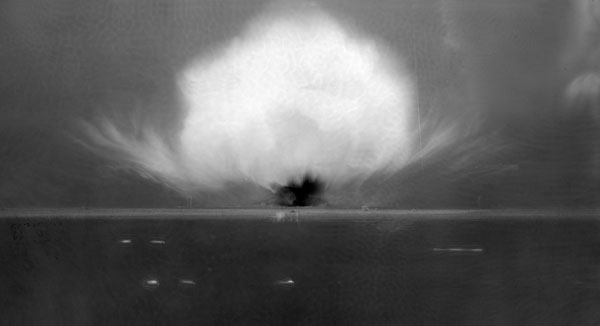

“A thousand simultaneous suns”: a long-exposure shot of the Trinity test.

So let’s step back and ask who Oppenheimer is meant to be in this situation. Oppenheimer is not Krishna/Vishnu, not the terrible god, not the “destroyer of worlds” — he is Arjuna, the human prince! He is the one who didn’t really want to kill his brothers, his fellow people. But he has been enjoined to battle by something bigger than himself — physics, fission, the atomic bomb, World War II, what have you — and only at the moment when it truly reveals its nature, the Trinity test, does he fully see why he, a man who hates war, is compelled to battle. It is the bomb that is here for destruction. Oppenheimer is merely the man who is witnessing it.

Hijiya argues that Oppenheimer’s sense of Gita-inspired “duty” pervades his life and his government service. I’m not sure I am 100% convinced of that. It seems like a heavyweight philosophical solution to the relatively lightweight problem of a life of inconsistency. But it’s an interesting idea. It is perhaps a useful way to think about why Oppenheimer got involved with so many projects that he, at times, seemed ambivalent about. Though ambivalence seemed readily available in those days — nobody seems to be searching for deep scriptural/philosophical justifications for Kenneth Bainbridge’s less eloquent, but equally ambivalent post-Trinity quote: “Now we’re all sons-of-bitches.”

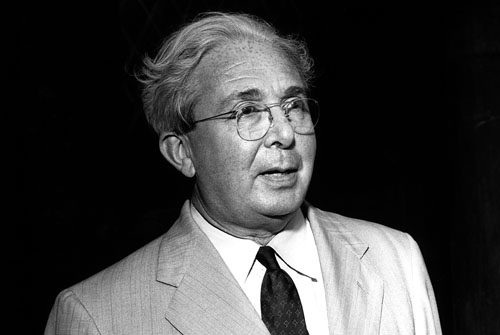

A rare color photograph of Oppenheimer from October 1945, with General Groves and University of California President Robert Sproul, at the Army-Navy “E” Award ceremony. Source.

One last issue that I find nagging me. We have no recording of Oppenheimer saying this except the 1965 one above. By this time, Oppenheimer is old, stripped of his security clearance, and dying of throat cancer. It is easy to see the clip as especially chilling in this light, given that is being spoken by a fading man. How would it sound, though, if it was coming from a younger, more chipper Oppenheimer, the one we see in photographs from the immediate postwar period? Would it be able to preserve its gravity?

Either way, I think the actual context of the quote within the Gita is far deeper, far more interesting, than the popular understanding of it. It isn’t a case of the “father” of the bomb declaring himself “death, the destroyer of worlds” in a fit of grandiosity or hubris. Rather, it is him being awed by what is being displayed in front of him, confronted with the spectacle of death itself unveiled in front of him, in the world’s most impressive memento mori, and realizing how little and inconsequential he is as a result. Compelled by something cosmic and terrifying, Oppenheimer then reconciles himself to his duty as a prince of physics, and that duty is war.

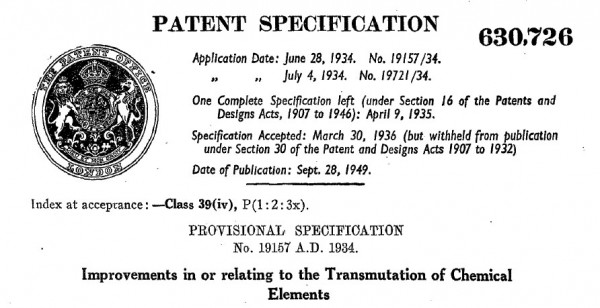

- James A. Hijiya, “The Gita of J. Robert Oppenheimer,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 144, no. 2 (June 2000), 123-167. [↩]

- Oppenheimer, in his 1965 interview, identifies the god as Vishnu, perhaps in error. Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu, however, so maybe it is technically correct along some line of thinking. [↩]