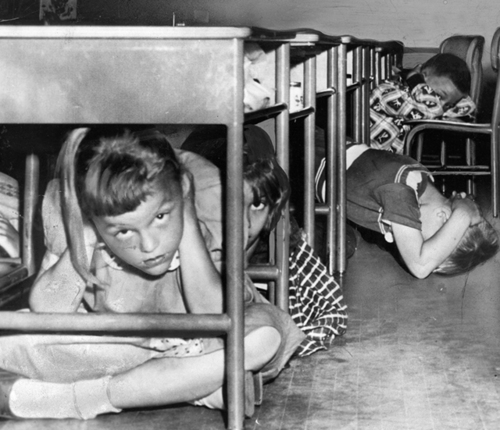

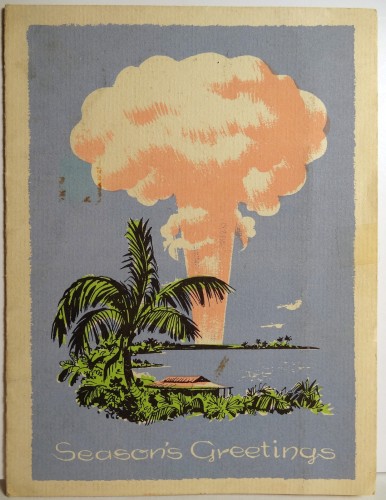

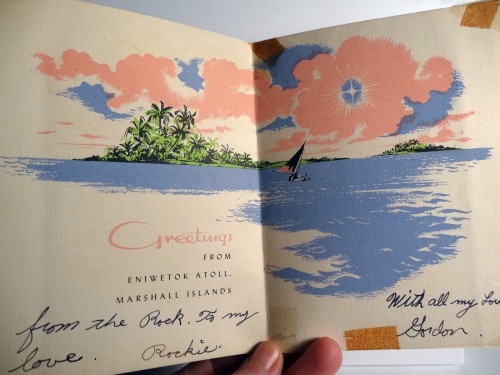

Hiding from nuclear attacks under ones school desks has got to be one of the most salient memories of Americans who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s. I get told about it with some regularity when I tell people about my work — the recollections of the “Duck and Cover” drills are spoken of with a sense of grim humor, in a tone of “can you believe they made us do that?”

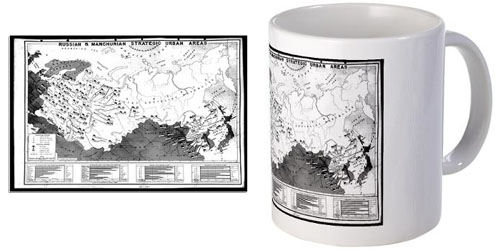

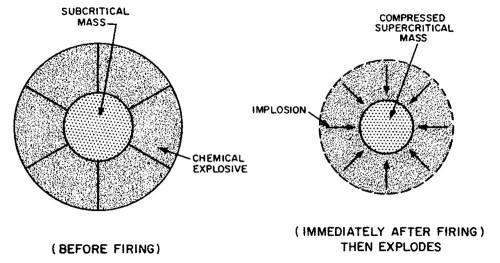

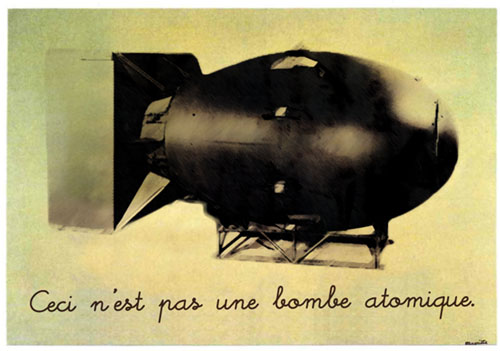

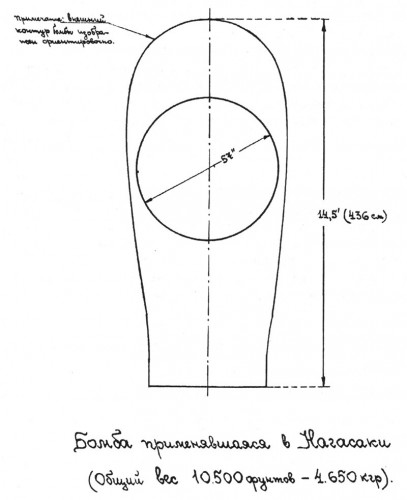

I’m not the world’s biggest critic of Civil Defense measures of this sort. Yes, Bert the Turtle is a bit condescending, but he was aimed at children, and for 1951 his message isn’t too far off. In 1951 the Soviets still lacked ICBMs and had bombs no more than double the yield of the Nagasaki weapon. Hiding under your desk probably wouldn’t help you much if the bomb went off right over your head, but could be significant for all of the people who were within a mile or so of the blast.

Civil Defense became a more problematic affair in the megaton and missile ages, especially since the Civil Defense planners were often kept out of the loop as to what the actual state-of-the-art was regarding bombs and tactics. There’s also a broader question about whether confidence (justified or not) in one’s ability to survive a nuclear attack drives states or individuals towards more dangerous behaviors with regards to nuclear weapons. But as a whole I think we’ve probably gone a little too far, culturally, in ridiculing Cold War Civil Defense measures — thanks in no small part by handling such as that in Atomic Café, which uses these films out of context.

I grew up in California in the late 1980s. I never did any “Duck and Cover” drills for nuclear threats — I wasn’t even aware of nuclear threats, to be honest. One of my first “political” memories is of the Berlin Wall coming down, when I was in the 6th grade. I remember being irritated, since I had just memorized which of the Germany’s was the “good” one and which was the “bad” one — no easy task for me at the time, given that the one with “Democratic” in its name was anything but!

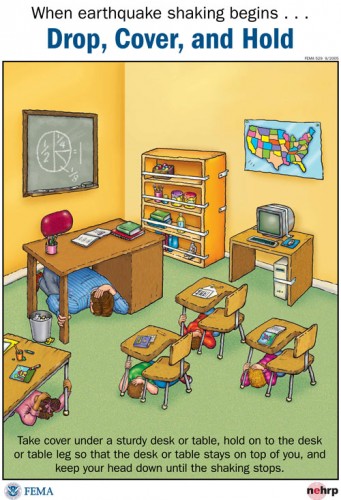

We did have drills, though. The most common were the standard fire drills that everybody does — flee (“leave your bags!”) and line up a safe distance from the school. Boring. Next on the list were earthquake drills, a staple in California. These are basically “duck and cover” drills with less fear. You hide under your desk, or you stand in a doorway. The hardest part about earthquakes is recognizing when one is happening; unless you’ve been through a few of them (I had some practice when I lived in Berkeley) it can take practically the length of the whole earthquake for your brain to realize exactly what’s going on. What I think people who haven’t been in one don’t realize is how strangely noisy they are — they make doors shake in their hinges, and it is a very unusual sound, and your brain (at least, my brain) takes a little time to process this, which makes it hard to act rapidly.1

But the most unusual drill we did where I grew up was something quite different, and I was reminded of it when I read about the massacre at the Sandy Hook Elementary School last week. I may digress a minute here.

“Stockton, California: These are the most interesting things we could find to photograph. Two of them are the same thing from different angles.”

I grew up in Stockton, California. It’s right in the middle of the long Central Valley that runs through the middle of the state; it’s about an hour-and-a-half drive northeast of the Bay Area, or a 45-minute drive south of Sacramento. “I’ve driven through there,” people often tell me. Rarely anybody knows much about it though, if they aren’t from California, despite its being a perennial favorite for top slots in Forbes’ America’s Most Miserable Cities list (#1 in 2009 and 2011!) and occasionally making the front-page of The New York Times for its economic woes (housing bubble, city government going bankrupt, and so on).

The reason you probably don’t know much about it is because there isn’t a whole lot to say, and certainly very little to romanticize. It doesn’t have a “company town gone bust” story (e.g. Flint), or a “former grandeur gone to squalor” (e.g. Baltimore), and nobody makes national commercials using it as some kind of comeback story (e.g. Detroit). It’s a medium-sized American city that has many of the problems of other medium-sized American cities, just more so. It’s problematic mixture of bad economy, crime, and mundanity isn’t glamorous, and it doesn’t fit into any of the well-worn American archetypes.

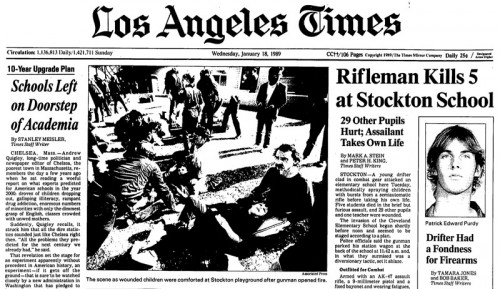

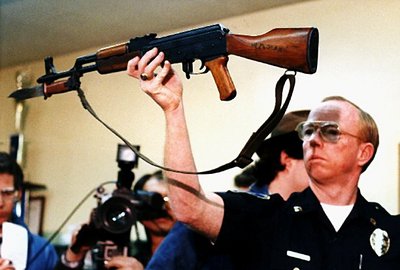

But we did have a school shooting. On January 17, 1989, a disturbed loner, Patrick Purdy, brought a Chinese-made AK-47 to the Cleveland Elementary School and started firing. He killed five children and wounded 30 others, including one teacher. He then killed himself. The victims were mostly from Cambodia and Vietnam — Stockton is one of the major hubs for South Asian refugees.

I didn’t go to Cleveland Elementary; I was on the other side of town. I want to make explicit that I’m not trying to co-opt any tragedy, whether the one at Sandy Hook or at Cleveland, nor am I claiming any special knowledge of these things. But I remember the day pretty clearly. Not out of horror — I don’t think I was old enough to really process horror very well — but just out of awe. How does one live in a city, or in a world, where this sort of thing happens? What do you, as a kid, even think of in such a situation? (I didn’t know much about my own mortality at age 8, so that didn’t really factor into it.)

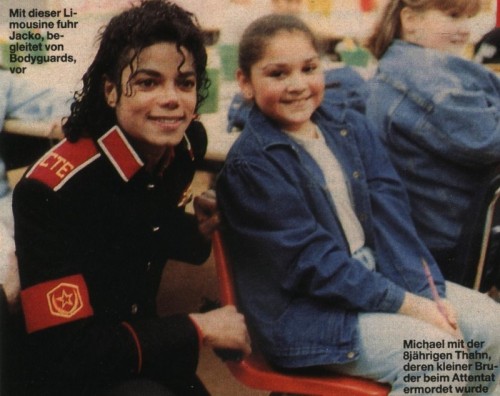

Stockton was in the national news — as always, just for something awful. Michael Jackson visited the city to show support for the children at Cleveland (very eighties). The state passed an assault weapons ban, part of a longer push for the Congressional assault weapons ban that was passed in 1994, and was allowed to lapse in 2004. The same ban that they are talking about revisiting today, as a result of Sandy Hook. As Michael Herr put it, “Those who remember the past are condemned to repeat it too, that’s a little history joke.”

But, to circle back, after the Cleveland massacre, all of the elementary schools in my town had “guy on campus with a gun” drills. Specifically, if the adult “yard duty” dropped to one knee and blew a whistle in three, long tones, we were all supposed to hit the deck. This wasn’t something we were just told, or that teachers had contingency plans for — we practiced it. I can remember this pretty vividly. It was our “Duck and Cover,” I suppose.

I’ve told this as stories to people before — prior to Sandy Hook — and their eyes widen, their mouth drops. Some have accused me of making it up! (I didn’t, and I’ve double-checked with others who I went to school with.) One friend of mine who grew up on the East Coast suggested that as children we must have been terrified. But I don’t remember being terrified. One isn’t terrified of fire when one is lining up outside, one isn’t terrified of earthquakes when one is standing in a doorway. The drills aren’t the thing. If anything, they’re either welcome interruptions to your daily routine, or they are boring activities involving standing in lines until everybody is accounted for.2

Human beings, especially children, have a tremendous capacity for normalizing the horrific, if it is presented to them as “normal,” if they live it as “normal.” We’ve gone, over the space of six plus decades, from teaching our children that they will be atom bombed by the Soviet Union, to teaching them that they will be shot by unstable loners. What was a war from above became a war from below.

“1989 file photograph: Stockton Police Capt. J.T. Marnoch holds up a Chinese-made AK-47 assault rifle that gunman Patrick Purdy used to kill five schoolchildren and injure 30 others at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton. (AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli, File)”

In a way, wars from below are always the scarier threats, the ones that keep families and policymakers up at night, even though their ability to do mass damage is considerably diminished most of the time. “Conventional” threats, like other nation-states, can be understood through the sanitized lens of game theory, rational actors, and deterrence. Such a lens might not actually tell you much about real world behavior, but it makes the problem seem solvable. Threats that seem to come from everywhere at once, from the social fabric itself, are necessarily more diffuse, appear un-categorizable, and sometimes seem to have cures that are worse than the disease.

I don’t know what the exact response to the Newtown massacre should be, other than a long, long-overdue patching up of gun sales loopholes and maybe a reinstatement of that lapsed assault weapon ban. But I’m glad it’s not my job to try and hash out the details, or try and sell them politically. I do hope, though, it goes beyond telling children to hide under their desks, to expect that they might have to “hit the deck” to hide from their fellow countrymen. The “Duck and Cover” drills of the Cold War were evidence of a dangerous international regime — one where a “full nuclear exchange” was seen as a likely future outcome. School-shooter “Duck and Cover” drills of yesterday and today are evidence that something’s very profoundly wrong with how we’re doing things in this country.

- When we had that earthquake in DC in 2011, I was completely prepared, I have to admit. I recognized it for what it was very rapidly, and moved to a doorway. All of that California training was put to use. Part of my rapidity, then, was that I was too daft not to realize that earthquakes were so very rare in the mid-Atlantic states, and so didn’t rationalize it away. I did, however, do a back-of-the-envelope reasoning about what the effects of a thermonuclear blast set off in DC would feel like at my office in College Park, Maryland… [↩]

- And in any case, Stockton had enough horrors to go around. Among other things, the apparent inspiration for that urban legend about flashing your headlights at gang members was the shooting of a secretary at my own elementary school. Even that is more sensational and unusual than the more quotidian threats that one felt in a city with a pretty high crime rate, gang problems, drug problem, etc. The place was once Steinbeck country, it’s now something more like Breaking Bad country. [↩]