In my last post, I talked about what the island of Tinian was like in World War II, when it served as the launching point for strategic bombing raids on Japan — including the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

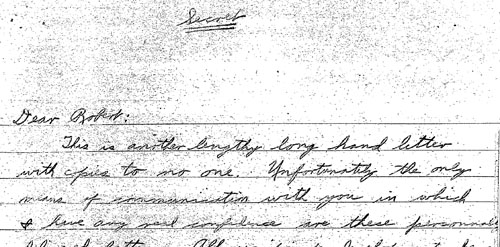

A physicist friend of mine from graduate school, Alex Boxer (who currently consults the Navy about submarines, and has his own history of science blog), recently took a vacation to Tinian, and took a ton of photographs. He’s given me permission to re-print some of them here, along with some of his comments on them (which are in italics).

You can begin your virtual tour of Tinian with this movie of what it’s like to fly there from Saipan. The planes are just little 6-seater prop-planes, and the flight is probably a grand total of 10 minutes. In this movie (sped-up 2x to reduce its size) you can see the whole island and what’s left of the North Field runways.

There’s very little to see that’s bomb-related — it’s striking, really, it’s almost as if the US military was never there. The only buildings which remain from that era are Japanese installations.

A random Japanese propeller located on the southern end of the island:

At North Field (located, sensibly enough, at the North end of the island) there are several Japanese buildings:

Description from a placard outside the building:

This two-story building was the World War II headquarters of the Japanese Navy’s 1st Air Fleet (Base Air Force of the Marianas), commanded by Vice Admiral Kakuji Kakuta. … Admiral Kakuta’s airfields in the Marianas and Iwo Jima served as staging areas for moving aircraft to southern Pacific battle areas and for attacks on American ships. By July of 1944, the airfields directed from the 1st Fleet headquarters had been captured or destroyed. What remained of Admiral Kakuta’s airplanes was destroyed in the naval battle of the Philippine Sea a month before the battle of Tinian. … When Americans captured Ushi Field, the headquarters building was abandoned and Ushi Field was a “ghost field” of abandoned airplane wrecks. The fate of Vice Admiral Kakuta is unknown, but was probably suicide or death. His last radio message to Tokyo was on July 30 as the battle of Tinian was nearing its conclusion. The massive concrete headquarters building was damaged by American artillery, but the building was repaired and used by American military officers after the invasion.

Another placard:

This building was the control center for the Japanese Navy’s 1st Air Fleet operations on Tinian, directing traffic on the runway to the south. It contained an office, the operations room, and a generator room. This is a standard design for World War II Japanese air operations buildings, with other examples located on Saipan and Chuuk. … The building was repaired and used as a control tower by the 20th Air Force after the B-29 runways of North Field were constructed here.

One more placard:

This massive power plant was probably build in 1939-1940 as part of the Japanese military construction of Ushi Field. the “bombproof” building was constructed of reinforced concrete and had steel shutters covering the windows. The building housed a 200 kilowatt power plant run by diesel fuel.

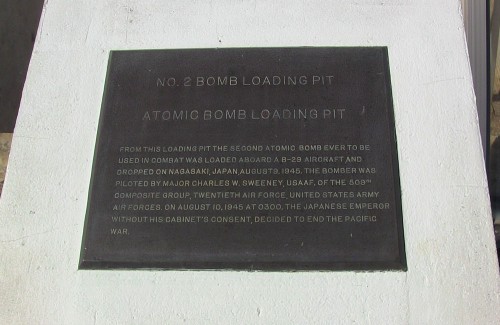

And here’s what you’ve been waiting for: bomb-pits! — The pits where Little Boy and Fat Man were loaded into the B-29s that dropped them on Japan.

I was somewhat dismayed at how little there was to see. It’s just two pits now under glass enclosures, somewhat like the entrance to the Louvre. The glass was also highly reflective which means that most of my photos didn’t come out very well.

Tinian was fantastic because it was one of the emptiest and quietest places I’ve ever been. I felt like I had the whole place to myself. However, there is nominally a tourist industry there which includes a rather shady hotel/casino. The tourists are mainly from Asia and Russia — there’s hardly anyone from the mainland US (a brief look at a map of the Pacific will make it clear why this is so). Anyways, our silent day was enlivened by a large tour-bus. I’m certain that these tourists are not Japanese; I’m almost, but not quite 100% certain that they are Chinese.

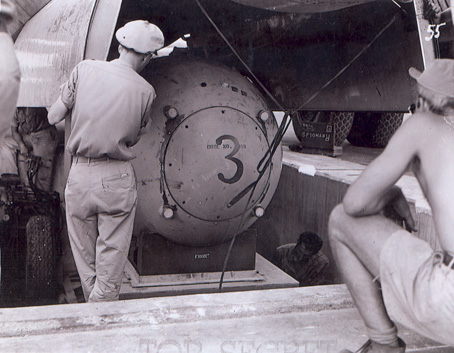

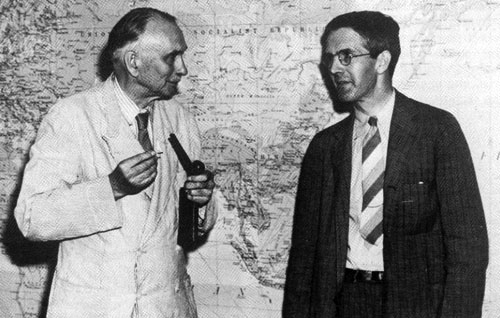

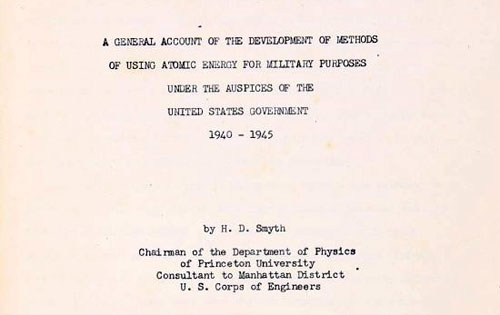

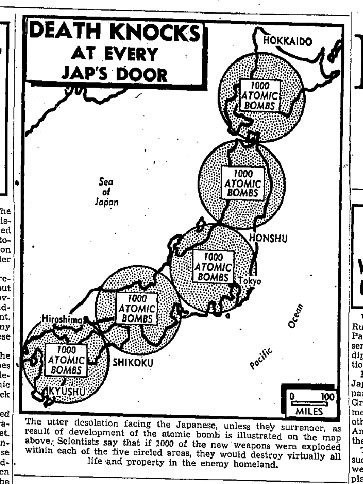

Interjection: just to compare, here are the actual loadings of Little Boy and a Fat Man test unit.

Or you could fly all the way to Tinian, and see the same sort of photos in the actual bomb pit:

Back to Boxer:

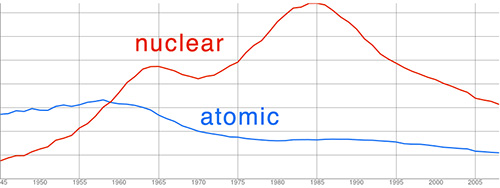

And as much as I’m an aficionado of atomic (or, rather, nuclear?) history, that wasn’t the main lure for me. Here’s what I really wanted to see on Tinian:

These are parts of the House of Taga:

The site is the location of a series of prehistoric latte stone pillars which were quarried about 4,000 feet south of it. Only one pillar is left standing erect. The name is derived from a mythological chief named Taga, who is said to have erected the pillars as a foundation for his own house. Legend says Chief Taga was murdered by his daughter, and her spirit is imprisoned in the lone standing megalith at the site.

I have to admit, I wasn’t aware that the only other tourist site on Tinian was just about as grim at the first atomic bomb loading pits.

And, just for fun, here’s a lovely photo of a Flame Tree:

Very cool. Let’s all give a little round of virtual applause for Dr. Boxer and maybe visit his website while we’re at it.

Now, you might be thinking — well, Tinian’s heyday has come and gone. And you might be right. But there’s been some interesting news about it from earlier this year:

Japan Self-Defense Forces officials will arrive today to discuss with CNMI officials their plans for Tinian where two-thirds of land are already leased by the U.S. Department of Defense, and the discussions could center around Japan’s plan to help fund a U.S. military base on Tinian or the training or stationing of their own forces there.

That’s right — there’s a chance (perhaps not a great one) that Tinian might yet be the site of a military base. What would be more appropriate — or inappropriate? — than Tinian becoming a joint US-Japanese military site?