Counterfactual history — or alternate history — is not a genre that most professional historians indulge in. We’re quick to sneer at it, for good reason: it’s pure fantasy, and about as relevant to history as Star Trek is to serious physics. (Star Wars is, unfortunately, another story.)

But sometimes the genre of What If? can be somewhat useful at pointing out assumptions in the current historical narrative. Controversial topics can cause us to get stuck in narrative ruts, parroting back the same sequence of events, taking for granted what did happen and losing sense of the contingency — the way in which things might have turned out otherwise.

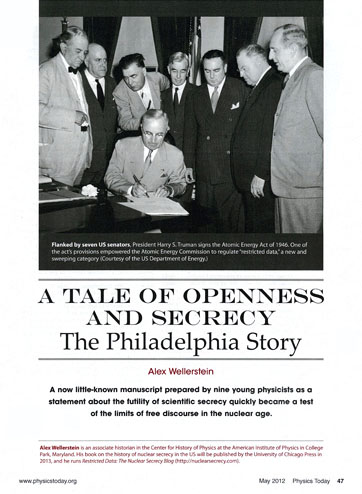

Hiroshima, October 1945. The domed structure in the far background, at right, was nearly directly under the bomb when it exploded. When showing such photos to students, I always point out that the reason there aren’t any corpses isn’t because they were vaporized — it’s because these photos were taken after they were already removed.

In the comment section of a post on here from last week, Michael Krepon of the Stimson Center (and Arms Control Wonk) posted an interesting hypothetical question:

What do you think would have happened differently had Japan not surrendered and if the US kept using atomic weapons when they were ready? We know what would have been the same: Japan would have lost the war. We can readily imagine what would have been different in Japan: more smoldering, radioactive rubble. But what would have been different outside of Japan?

I strangely wonder about the question. I suspect that there would have been an open revolt at Los Alamos. Would Truman have said, “enough”? Would attitudes about the Bomb in the US & Russia have been any different? Attitudes toward the US?

It’s worth noting explicitly that this is a very different question to the “what if we hadn’t dropped the bomb at all?” question, which is more common and has some pretty well-worn narrative ruts (deaths of bomb vs. invasion, whether demonstration would have worked, the importance of the Soviets invading Manchuria vs. the bomb, etc.). This query presumes that Hiroshima and Nagasaki happened as they did, but instead of surrendering shortly thereafter, the Japanese had kept on going, and Truman had OK’d the dropping of more bombs.

I gave some gesture at a response, synthesizing some interesting work that I thought was relevant to the issue. I also managed to get Michael Gordin, author of Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War, to chime in as well. You can read the responses at the post linked to above.

How realistic is the question? Pretty realistic, as it turns out. As Michael G. argued in his book, the notion that “two bombs were enough” wasn’t actually dominant at the time — some people thought it would be “enough,” but most people, naturally, had no idea how many would be “enough.” In early August 1945, nobody knew whether the atomic bombs would be the “war-ending weapons” that they were later (controversially) touted as being. Only after surrender do you really get into the idea that two are “enough,” if not too much.

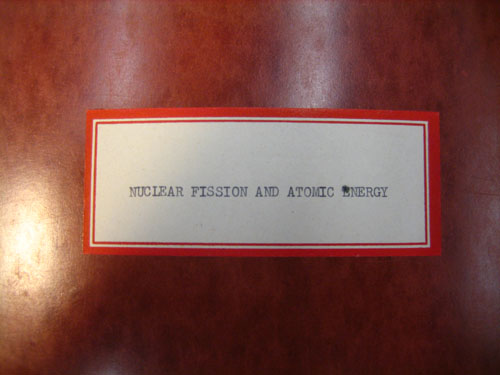

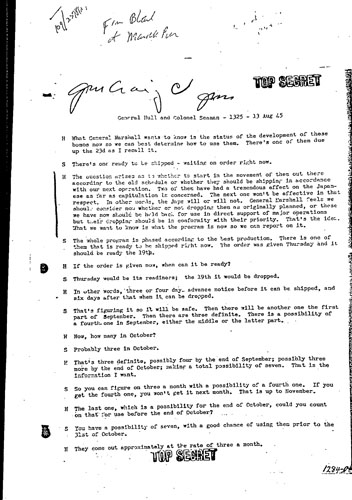

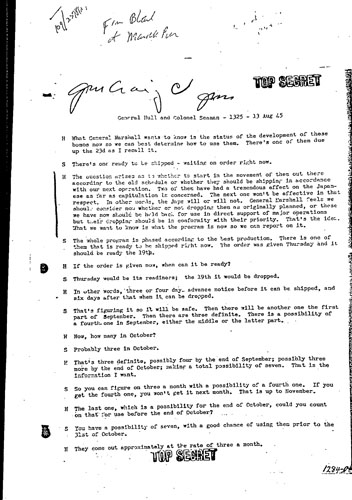

This week’s document is one of the more vivid demonstrations of this fact. It is a transcript of a telephone conversation between General John E. Hull, who was involved in Allied planning in the Pacific theatre, and Colonel L.E. Seeman (here incorrectly noted as “Seaman”), an assistant of Groves, on August 13, 1945. The subject is the “third shot” — the next bomb ready for use after Nagasaki, which was anticipated to be ready by August 23 — and the shots beyond that.

Click for the PDF.

From the transcript:

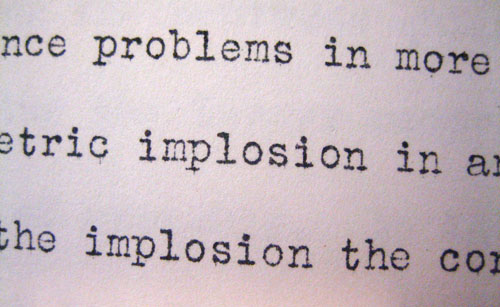

- S[eaman]: … Then there will be another one the first part of September. Then there are three definite. There is a possibility of a fourth one In September, either the middle or the latter part.

- H[ull]: Now, how many in October?

- S: Probably three in October.

- H: That’s three definite, possibly four by the end of September; possibly three more by the end of October; making a total possibility of seven. That is the information I want.

- S: So you can figure on three a month with a possibility of a fourth one. If you get the fourth one, you won’t get it next month. That is up to November.

- H: The last one, which is a possibility for the end of October, could you count on that for use before the end of October?

- S: You have a possibility of seven, with a good chance of using them prior to the 31st of October.

- H: They come out approximately at the rate of three a month.

That’s a lot of bombs. (Incidentally, this also lets you estimate the maximum stockpile size throughout much of the late 1940s. In practice, bomb production fell off in the confusion at the end of the war, and didn’t pick up again until 1948 or so.)

- H: That is the information I wanted. The problem now is whether or not, assuming the Japanese do not capitulate, continue on dropping them every time one is made and shipped out there or whether to hold them up as far as the dropping is concerned and then pour them all on in a reasonably short time. Not all in one day, but over a short period. And that also takes into consideration the target that we are after. In other words should we not concentrate on targets that will be of the greatest assistance to an invasion rather than industry, morale, psychology, etc.

- S: Nearer the tactical use rather than other use.

“The other use”: what a euphemism! Though perhaps no worse than “strategic bombing,” which is a nicer formulation than “terror bombing” (as it was, for awhile, originally called, in the context of firebombing). This idea of one-bomb-as-you-get-them or holding them up and then “pour[ing] them all on” is one of the ones that has stuck with me. A “rain of ruin” indeed. It’s tempting to imagine this as periods of peace punctuated by periods of terrible destruction, but it’s probably worth noting that there would have likely been firebombing during those “peaceful” periods as well, so there’d be a lot of terrible destruction to go around.

Read the full post »