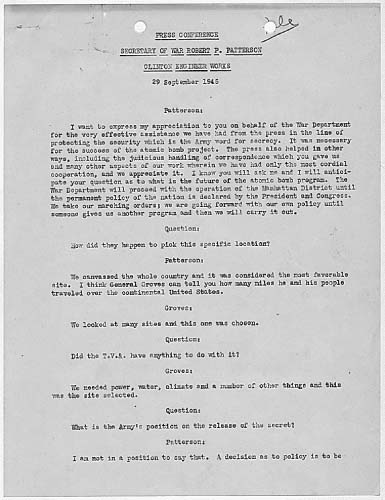

“OPSEC” is governmentspeak for “operations security.” In practice, OPSEC programs are usually devoted to coming up with creative ways to remind employees to keep secrets, and investigate breeches of secrecy. Google Ngrams suggests the term was birthed in the mid-1970s or so, and has proliferated since then. In the earlier Cold War, these functions were just dubbed “Security” by the Atomic Energy Commission.

“Silence Means Security” — Cold War “OPSEC” billboard from Hanford Site. (Hanford DDRS #N1D0023596)-

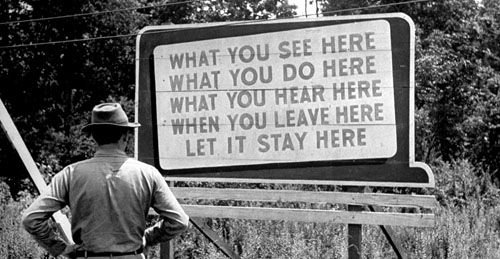

The media output is of course what I find most interesting — the ways in which employees, in the name of OPSEC, are cajoled, and often threatened, into maintaining strict cultures of secrecy. This sort of activity is a common and integral part of a secrecy system, because if you aren’t “disciplining” the employee (to invoke a little Foucault) into acting contrary to the way they are accustomed to, the whole thing becomes as leaky as a sieve. It’s not a new thing, of course, and we’ve already seen a few historical examples of this on the blog.

Sometimes it is done well — strong message, strong artistic execution. And sometimes… it is done less well.

The DOE OPSEC logo from the Arnold OPSEC era. “Propugnator causae” is something like, “Defender of the Cause.”

In the category of “less well” falls a series of OPSEC videos the DOE Nevada Operations Office put together in what looks like the late 1980s or early 1990s, featuring the hapless character “Arnold OPSEC.” They are little film clips (non-animated) demonstrating poor, dumb Arnold OPSEC as he accidentally divulges classified information through clumsy practices.

The DOE has helpfully put all of these online for your viewing pleasure. A few of my favorites follow. (You will probably need QuickTime Player to view these.)

Arnold goes jogging (and blabbing) with his “new friends,” who happen to be Soviet spies! D’oh!

Arnold gets a cell phone the size of his head and uses it to blab about secrets while driving his sports car.

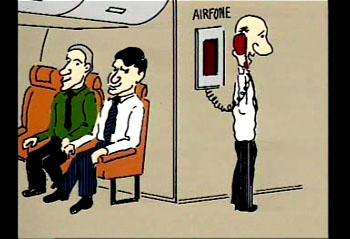

Arnold uses an “airfone” on a plane, brags how important he is to his girlfriend, and nefarious terrorists hear him, and then hijack the plane and keep him as an important hostage. Sometimes your days just don’t work out.

Arnold gives a tour of Nevada Test Site, and tells a bunch of obvious-shady visitors (check out those evil eyebrows) things he shouldn’t, so his supervisor (who is mysteriously missing legs) dresses him down.

Arnold takes work home to use on his new-fangled PC and modem service, “Prodigy,” and accidentally posts it all onto the new-fangled Internet. (And you thought WikiLeaks was a new thing!)

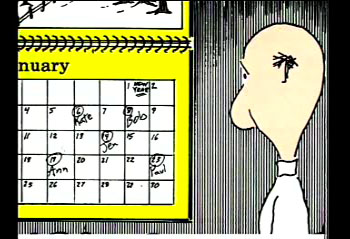

Arnold irritates everyone at the office by publishing their birth dates and Social Security Numbers. “Arnold just doesn’t realize the kinds of information that can be considered sensitive!” Arnold is both a leak and a jerk.

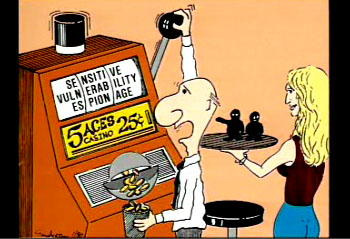

“Help make our security a sure-thing. Don’t gamble with OPSEC.” I find this one very perplexing. It’s not a real situation. It’s a metaphor, you know? Arnold is gambling with OPSEC, and hit the jackpot of, um, espionage. Then he is being served little black men by a blond woman whose dimpled rear has received a little too much artistic attention. So don’t, um, do any of that. Got it?

It’s a recurrent theme in these that new-fangled technology is the result of a lot of leaks. The Information Age did create a lot of challenges for places where information flow was meant to be restricted, not encouraged. Still, I can’t help but feel sorry for the poor employees who must have been forced to sit through these scoldings.