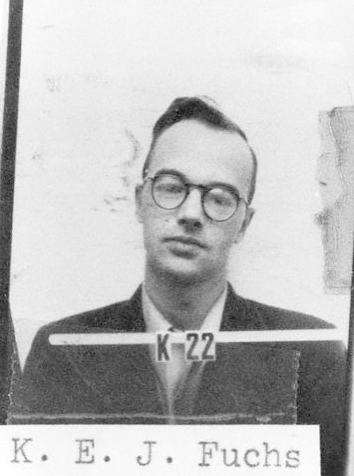

The quality of the photocopy isn’t as good as the original, but I like the stark contrast it created. It also worked well with the color process (the whole poster is just black, white, and blueish) that we used.3 Only much later did I figure out that the photographer was Steltzer. She was kind enough to ship me a darkroom reproduction of the original contact sheet, which is stunningly beautiful.

Over e-mail, I asked Ulli about her sessions with Oppenheimer. This was her response to me:

I am glad you like the proof sheet. It is one of several, though I only took O.’s picture four times. The first time I was so exited, that all the pictures were out of focus. Your proof sheet is from the second time. He was shy of the camera and I never got more than 12 shots. It is hard to say which expression is most typical. Priscilla chose a very different picture from Kai Bird. And I have one of the friendly ones here, with the pipe and a smile. Was he an easy or difficult guy to photograph? He asked me to come and take the pictures at different times and occasions, but I never stayed longer than 8 or 10 minutes because he would soon say that it was enough. … When you say “anything you could remember would be appreciated”…..I could not write a book, but I do have many profound memories of conversations with Oppenheimer, enough to justify any expression of his that I was able to catch on film. A man of his depth and complexity can not be easily portrayed in one frame. This is why I can truly appreciate your wanting the proof sheet.4

I thought the portions I’ve bolded above were pretty interesting. I like the idea that someone of Oppenheimer’s richness — sometimes one thing, sometimes another — defies the static notion of the photograph, and perhaps a static notion of a narrative character. Sometimes he’s smiling at you, elfin, almost winking. Sometimes he’s brooding and dark. Sometimes he looks the haunted martyr, sometimes he looks proud. All within the span of 10 minutes or so.

- Contact sheets are used by photographer to figure out which of their negatives are worth developing. Any photographer, or anyone who took a photography class in high school, knows this, but I wonder how obscure this fact will be in an age of cheap digital photography. Don’t mistake this for nostalgia on my part — I never saw much glory in smelling like chemicals all day! Though there is something intimate about the darkroom that doesn’t quite carry over to Photoshop. [↩]

- It’s a little cheesy of me to use a poster that I designed as the Friday Image, but it’s really because I’m still in love with the original image that makes it work. [↩]

- These days, cheap color laser printing is extremely easy to do, but at the time for whatever reason we were using some sort of color separation process. The final result is beautiful but it ended up being a huge hassle. We had told the printers we wanted it to be two colors — meaning black and blue. We hadn’t realized they were considering white — the absence of color — to be a color. For whatever reason, we didn’t get a proof made. What we received from the printer was horrible: instead of black, white, and blue, it was entirely blue and white, where everything you see as black in the above was rendered as the blue color. It took a lot of e-mails with the printer for them to re-print it again on short notice. I can’t remember whether we ended up having to pay some of the second run as well — it wasn’t really clear whose fault this was supposed to be, though I had felt that the fact that the printed work looked nothing like the digital files we had provided might have been a tip-off to a competent printer, and probably override the fact that my language in describing it had been imprecise. It also didn’t help that they tried to fake some of their e-mails to make it sound like they were in the right. Anyway, you live and you learn. This was my first big poster printing job, and I learned a lot from it — as one does from all survived disasters. [↩]

- E-mail reproduced with permission. [↩]