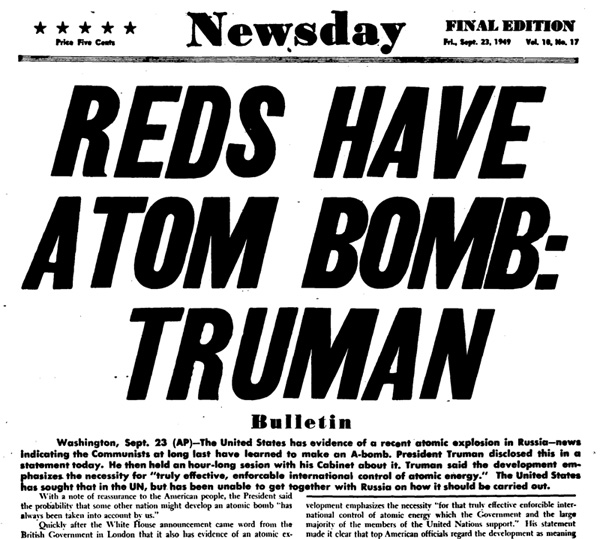

In September 1949, the United States unambiguously detected radioactive residues which indicated that the Soviet Union had, some weeks before, detonated their first atomic bomb. President Truman was initially inclined to keep the discovery secret, to avoid panic among Americans and their foreign allies, but was convinced by his advisors, including an impassioned David Lilienthal, head of the Atomic Energy Commission, that this was folly. The Soviets, they argued, would likely be announcing it soon anyways, and it would look better for the US to show that it was on top of things and unruffled by these developments. Truman finally agreed, and released a short statement indicating that an “atomic explosion” had taken place in the USSR (he was deliberately coy on whether it was a bomb or not), and indicating that this was entirely in accord with expert predictions about Soviet capabilities (not entirely true, but not entirely false).1

Extra, extra, read all about it! You’ve got to love the appearance of these old dailies…

What should the US response be to the loss of its nuclear monopoly? This question raged in the weeks afterwards. One of the proposals, led by Edward Teller and championed by AEC Commissioner Lewis Strauss, was to push for an even bigger weapon: the “Super,” or hydrogen bomb. The Super would dwarf fission weapons, it was believed, and show the American people, America’s foreign allies, and America’s foreign enemies who exactly was in charge. As momentum grew behind this still-secret push for a “crash” H-bomb program, opposition emerged. J. Robert Oppenheimer and the AEC’s General Advisory Committee would, in late October 1949, issue a scathing report that condemned the idea on technical, policy, and moral grounds. Not only would a crash program divert vital resources from the US fission weapons program at a crucial time (and they not only did not know how to make an H-bomb in 1949, they didn’t even know for sure that it could be built), but a world with H-bombs would ultimately be more dangerous for the United States than the Soviets (because the US keeps so much of its people and wealth in large, concentrated cities on the vulnerable coasts), but a weapon in the megaton range was potentially a weapon of “genocide” (their wording), and thus not compatible with American values.2

This “H-bomb debate,” as it was and is called, was originally completely within the secret sphere. The fact that it was taking place was not known to the broader public, despite its weighty potential implications for the nation. Eventually, on November 1949, it would leak to the public. The way in which that happened is one of the most bizarre and absurd situations in American nuclear secrecy — and I describe it in my NEW BOOK, Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States (obligatory plug!).3

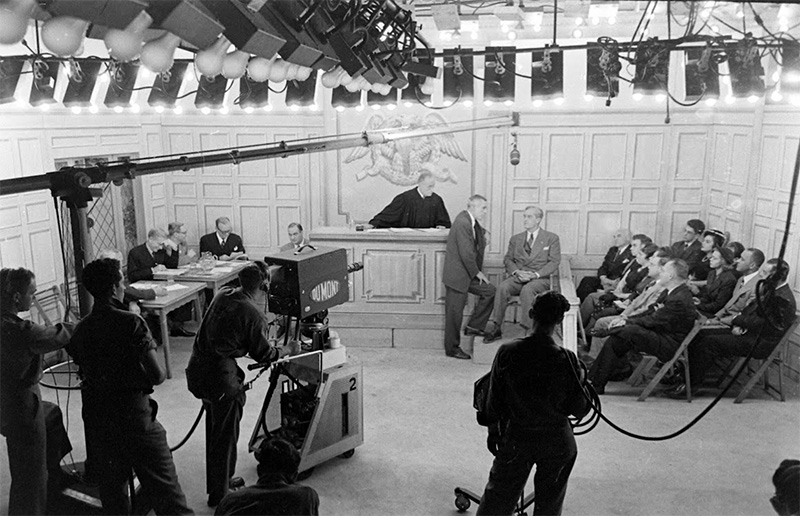

A photograph from the set of Court of Current Issues, October 1948. I don’t have any photographs of the episode in question, but this gives a sense of what it might have looked like. Source: Cornell Capa for TIME/LIFE via Google

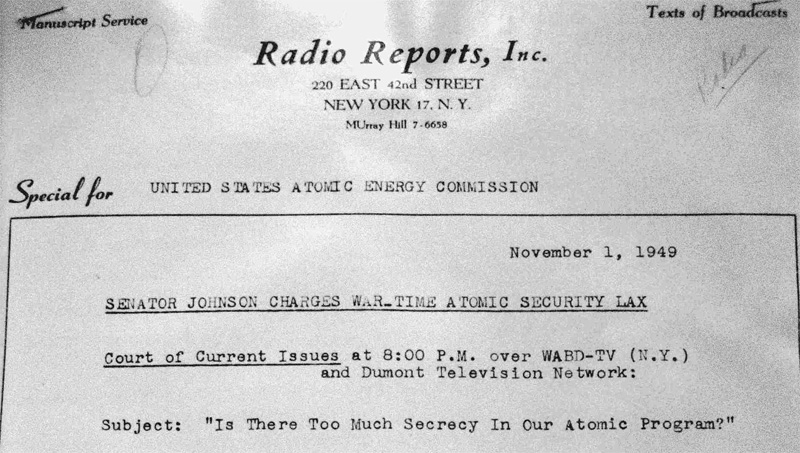

What happened is this: on November 1, 1949, at 8:00pm Eastern Time, a television show called “Court of Current Issues” aired on the WABD-TV (New York) and Dumont Television Network. The show was essentially a debate program, framed as a courtroom in which various experts would argue as if they were prosecuting the “current issue” as a court case. This episode’s subject was: “Is there too much secrecy in our atomic program?”

The “witnesses” included two scientists (Hugh Wolfe, physicist of Cooper Union and chair of the Federation of American Scientists, and Harrison Brown, physicist at the University of Chicago), a science journalist (Michael Amrine, who was also a staff member at FAS), an FBI agent (Edward Conroy, of the NYC office), a Manhattan Project security officer (Col. William Consodine, former Manhattan Project head of security and intelligence, and one of the technical advisors for the bizarre MGM Film, The Beginning or the End?), and, importantly, Senator Edwin Johnson, Democrat of Colorado and member of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, the key Congressional committee with oversight of the US nuclear program, which was itself pushing hard in favor of building the H-bomb.

“Is there too much secrecy in our atomic program?” Find out for yourself by reading the transcript of Senator Johnson’s comments.4

Consodine, the security officer, and Amrine, the journalist, acted as the “lawyers” in the debate, examining and cross-examining the “witnesses.” The scientists said there was too much security in the present atomic program, the FBI agent and Senator Johnson said there was not. During Consodine’s questioning of Johnson, he said a number of things that frankly would have counted as leaks at the time. When asked about how tight Soviet security was, Johnson explained that: “Russian security is airtight. Very little leaks from there. As a matter of fact, we haven’t been able to get anything through, and we have some of the greatest experts in the world with big ears who’d like to know something about and not even a whisper comes through the iron curtain, not a whisper.” (Any statement on what intelligence capabilities the US did or didn’t have — even a misleading one, and this is somewhat misleading — would have been classified at the time.)

In his cross-examination, Amrine put to Senator Johnson the question that, if the point of nuclear secrecy was to keep the Soviets from getting the atomic bomb, and the Soviets now had it… didn’t that mean we might not need the secrecy with them anymore? Since they knew the secret? Shouldn’t the US relax its secrecy since, as he put it, “the main cat out of the main bag?” Johnson disagreed strongly: “I don’t think you can be strict enough with that sort of thing, because lives of millions of Americans hang in the balance and because the scientists all have a yen, like some old fisherwoman, to tell all we know… The scientists have a passion for telling everything that they know.”

Amrine then asked Johnson that if the Soviets knew how to make an “atomic pile” (nuclear reactor), why shouldn’t we declassify our own program on the same subject in order to advance it? Johnson’s reply was a bombshell, if a rambling non-sequitur (emphasis added):

I’m glad you asked me that question, because there’s the thing that is top secret. Our scientists from the time that the bombs were detonated at Hiroshima and Nagasaki have been trying to make what is known as a superbomb. They’ve been devoting their time to two things: one, to make a superbomb, and the other, to find some way of detonating a bomb before the fellow that wants drop it can detonate it. And we — we’ve made considerable progress in that direction. Now, there’s no question at all that the Russians have a bomb more or less similar to the bomb we dropped on Nagasaki, a plutonium bomb. Our scientists are certain that they have that bomb, but it’s — it’s not a better bomb than dropped at Nagasaki. Now our scientists already — already have created a bomb that has six times the effectiveness of the bomb that was dropped at Nagasaki and they’re not satisfied at all; they want one that has a thousand times the effect of that terrible bomb that was dropped at Nagasaki that snuffed out the lives of — of fifty thousand people just like that. And that’s the secret, that’s the big secret that the scientists in America are so anxious to divulge to the whole scientific world.

Johnson said a lot of things that he shouldn’t have. Even mentioning that there was some research done into “pre-detonating” a bomb would have been classified (I don’t know anything about this, but it would be entirely unsurprising that this idea was looked into). He claims that the US had developed a bomb with “six times the effectiveness” as the Nagasaki one — this is a bit of hyperbole for late 1949, no matter how you slice it, but still a subject he would not have been permitted to speculate about or discuss, since it pertained to results from the recent Operation Sandstone test series.5 And identifying the Soviet bomb test as being a plutonium implosion device was also at that moment quite classified, because it would have revealed fairly plainly how the US actually determined the Soviets had tested a weapon (it points to radiological analysis, as opposed to, say, seismographic observation).

But of course the real amazement comes from the line about the “Superbomb.” If they relaxed the secrecy, Johnson argued on television, the scientists would tell you that they are working on a weapon with a thousand times the yield of the Nagasaki bomb, and that is the “top secret” that would be let out… thus letting it out.

Senator Edwin C. Johnson looks over the shoulder of President Harry Truman while the latter signs a bill, July 31, 1946. Source: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Amusingly, Johnson takes the same pose in another photograph a few days later, when Truman signs the Atomic Energy Act of 1946.

The absurdity of the situation is remarkable. Could Johnson have really been so self-unaware that he did not see the contradiction inherent to announcing on television the information that you are arguing needs to be kept “top secret”? I mean, he was a Congressman, so anything is possible. Could he have done it on purpose, in order to bring the H-bomb debate to the public? It’s tempting to suspect that — especially in light of what happened afterwards, which I’ll get to in a moment — but frankly when I read the transcript, it doesn’t at all look like some pre-mediated leak. It looks like a rambling statement meant to win an argument.

Interestingly, in the rest of Johnson’s “testimony,” he does aver to secrecy at one point — when Amrine asks him about the possibility of radiological warfare (which is identified by Johnson and Consodine as a “top military secret,” even though the possibility of it was not exactly secret at that point and was, as Amrine noted, explicitly mentioned in the Smyth Report). Maybe too little, too late? The only other aspect of the “testimony” of interest is on Civil Defense — which had not really gotten started in the United States, but would soon — in which Johnson noted (more sensibly than much else that he said) that if you tell people to get prepared for atomic war and then it never happens, they may end up losing interest in it.

Remarkably, Johnson’s leaks weren’t immediately picked up more broadly. Television was more ephemeral then than it is today (hence we have no footage of it), and it’s possible that it might have been ignored altogether — aside from the AEC’s transcription practices — had not, over two weeks later, that an article ran about it on the front page of the Washington Post. Johnson was quoted in the article saying everything that he had said came from “public sources” and “simple logic” which was clearly (and self-evidently!) false.6

The front page of the Washington Post, November 18, 1949, featuring the discussion of Johnson’s leak. I always find looking at historical newspapers fascinating because of the juxtaposition of stories. Here you’ve got the Loon weapon system (an early cruise missile evolved from the V-1 rocket) on the left, two B-29s colliding midair at bottom right, and a mysteriously poisoned cabbie at bottom left, with H-bomb secrets smack dab in the middle!

As an aside, the editorial writers for the Post were also puzzled by what Johnson could have been thinking: “Whether Senator Johnson supposed that this telecast was strictly off the record or that the entire audience had been carefully investigated and cleared by the FBI, we cannot say.” On Johnson’s claim that scientists had a yen for gossip, they quipped that: “Of course, the scientists knew about atomic energy long before Senator Johnson had ever learned to distinguish a neutron from a neurosis, and no one ever found about it from eavesdropping a television program.” They concluded that Johnson ought to “preach what he practices.”7

In any event, from that moment on, the “H-bomb debate” was a matter of public record, and sources inside and outside of the government weighed in on whether the United States should or should not pursue this new possibility. And this infuriated Truman. David Lilienthal met with the President that day and noted in his diary that “the President was mad as hops, [and he] started off by cussing Johnson and the Joint Committee out.” Truman immediately demanded that the Joint Committee plug their leaks. But more leaks would come about the nature of the “Super,” and the discussions behind had behind the cloak of secrecy. Finally, Truman asked the National Security Council to give him a recommendation on the “Super” question. They argued in favor of making the bomb (but not as a “crash” program, per se). Lilienthal argued against it, and Truman’s reply to him, as Lilienthal recalled in his diary, was telling: “we could have had all this re-examination quietly if Senator Ed Johnson hadn’t made that unfortunate remark about the super bomb; since that time there has been so much talk in the Congress and everywhere and people are so excited he [Truman] really hasn’t any alternative but to go ahead and that was what he was going to do.In other words, the Johnson’s leak — as bizarre as it is — probably is what led Truman towards making a decision on the H-bomb in the first place, forcing his hand because the matter had taken on such a public stature (and the general public, and Congress, were extremely favorable with regards to the idea of the H-bomb). Such is the power of selective information release in a regime of secrecy!

It had one other consequence, as well. Truman’s official statement on the H-bomb question, made on January 31, 1950, carefully says that “I have directed the Atomic Energy Commission to continue its work on all forms of atomic weapons, including the so-called hydrogen or superbomb,” deliberately not making it sound like the work hasn’t already been taking place, or that it is a “crash” program. Along with this, he issued a Top Secret directive to the AEC which said the same thing as the public one, except for one additional clause at the end: “I have also decided to indicate publicly the intention of this Government to continue work to determine the feasibility of a thermonuclear weapon, and I hereby direct that no further official information be made public on it without my approval.” Truman put a “gag” order in place on the H-bomb, no doubt an additional bit of fallout from Johnson’s disastrous leak.

Obligatory plug: If you want more on the H-bomb “gag” order, check out chapter 5 of Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States (University of Chicago Press, 2021), which talks about it in detail!

- The story of the US detection of and response to the Soviet test is very well-told in Michael Gordin, Red Cloud at Dawn: Truman, Stalin and the End of the Atomic Monopoly (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009). [↩]

- This is a highly-abbreviated presentation of the arguments of the H-bomb debate; for a much longer and comprehensive one, see Peter Galison and Barton Bernstein, “In any light: Scientists and the decision to build the superbomb, 1942-1954,” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 19, no. 1 (1988), 267-347. [↩]

- And, of course, as I look up the section in the book that describes it, I notice it has a typo on it! Sigh… on page 219, it should say “November 1949” where it instead says “November 1950” on the first sentence of the page. Fortunately it is rather clear from the context before and after, as well as the footnote, that this is a typo… but still. Argh! These sorts of things are like a dagger to the heart. [↩]

- Radio Reports, Special for the Atomic Energy Commission, “Senator Johnson Charges War-Time Atomic Security Lax [transcript],” Radio Reports, Inc. (1 November 1949), in Office files of David E. Lilienthal, Records of the Office of the Chairman, Records of the Atomic Energy Commission, Record Group 326, National Archives and Records Administration, Archives II, College Park, MD, Box 16, “Radio—Matters, Re.” [↩]

- Operation Sandstone, in 1948, tested several design approaches — including levitation and composite cores — that increased both the explosive power of the stockpile and increased the efficiency of fuel use, which allowed for some radical increases in yield and an increase in the number of bombs available. From 1949-1952 or so, these changes were being implemented in the stockpile and would eventually lend to some truth to the “6 times more efficient/explosive than the Nagasaki bomb,” but in late 1949 this was still not totally implemented. [↩]

- Alfred Friendly, “New A-Bomb Has 6 Times Power of 1st,” Washington Post (18 November 1949), 1. The Post article claims the delay was because they did not receive the transcript until then, and that the television station had declined to release the transcript for publication until it could get permission from all people who had participated, which it could not obtain. The Post doesn’t then elaborate how it got it, but it sounds like it got leaked to them from someone at the company or — less likely, in my view — the AEC. [↩]

- “Sen. Johnson on secrecy,” Washington Post (21 November 1949), 10. [↩]