The first history of the Manhattan Project that was ever published was the famous Smyth Report, which was made public just three days after the bombing of Nagasaki. But the heavily-redacted Smyth Report understandably left a lot out, even if it did give a good general overview of the work that had been done to make the bomb. Deep within the secret files of the Manhattan Project, though, was another, classified history of the atomic bomb. This was General Leslie Groves’ Manhattan District History. This wasn’t a history that Groves ever intended to publish — it was an internal record-keeping system for someone who knew that over the course of his life, he (and others) would need to be able to occasionally look up information about the decisions made during the making of the atomic bomb, and that wading through the thousands of miscellaneous papers associated with the project wouldn’t cut it.

Groves’ concern with documentation warms this historian’s heart, but it’s worth noting that he wasn’t making this for posterity. Groves repeatedly emphasized both during the project and afterwards that he was afraid of being challenged after the fact. With the great secrecy of the Manhattan Project, and its “black” budget, high priority rating, and its lack of tolerance for any external interference, came a great responsibility. Groves knew that he had made enemies and was doing controversial things. There was a chance, even if everything worked correctly (and help him if it didn’t!), that all of his actions would land him in front of Congress, repeatedly testifying about whether he made bad decisions, abused public trust, and wasted money. And if he was asked, years later, about the work of one part of the project, how would he know how to answer? Better to have a record of decisions put into one place, should he need to look it up later, and before all of the scientists scattered to the wind in the postwar. He might also have been thinking about the memoir he would someday write: his 1962 book, Now it Can Be Told, clearly leans heavily on his secret history in some places.

Groves didn’t write the thing himself, of course. Despite his reputation for micromanagement, he had his limits. Instead, the overall project was managed by an editor, Gavin Hadden, a civil employee for the Army Corps of Engineers. Individual chapters and sections were written by people who had worked in the various divisions in question. Unlike the Smyth Report, the history chapters were not necessarily written near-contemporaneously with the work — most of the work appears to have been started after the war ended, some parts appear to have not been finished until 1948 or so.

In early August 1945 — before the bombs had been dropped — a guide outlining the precise goals and form of the history was finalized. It explained that:

The purpose of the history is to serve as a source of historical information for War Department officials and other authorized individuals. Accordingly, the viewpoint of the writer should be that of General Groves and the reader should be considered as a layman without any specialized knowledge of the subject who may be critical of the Department or the project.

Which is remarkably blunt: write as if Groves himself was saying these things (because someday he might!), and write as if the reader is someone looking for something to criticize. Later the guide gives some specific examples on how to spin problematic things, like the chafing effect of secrecy:

For example, the rigid security restrictions of the project in many cases necessitated the adoption of unusual measures in the attainment of a local objective but the maintenance of security has been recognized throughout as an absolute necessity. Consequently, instead of a statement such as, “This work was impeded by the rigid security regulations of the District,” a statement such as, “The necessity of guarding the security of the project required that operations be carried on in — etc.” would be more accurate.

This was the history that Groves grabbed whenever he did get hauled in front of Congress in the postwar (which happened less than he had feared, but it still happened). This was the history that the Atomic Energy Commission relied upon whenever it needed to find out what its predecessor agencies had done. It was a useful document to have around, because it contains all manner of statistics, technical details, legal details, and references to other documents in the archive.

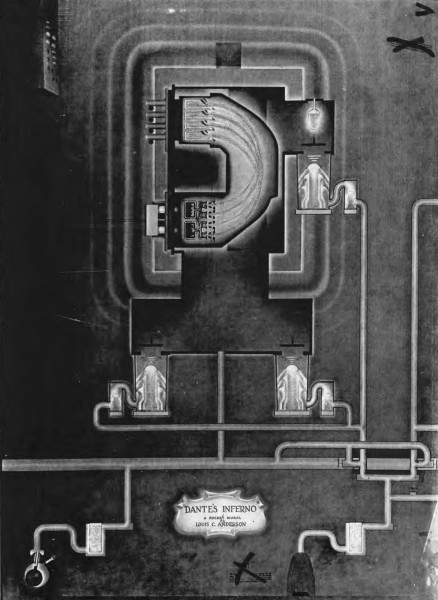

“Dante’s Inferno: A Pocket Mural” by Louis C. Anderson, a rather wonderful and odd drawing of the Calutron process. From Manhattan District History, Book 5, “Electromagnetic Project,” Volume 6.

The Manhattan District History became partially available to the general public in 1977, when a partial version of it was made available on microfilm through the National Archives and University Publications of America as Manhattan Project: Official History and Documents. The Center for Research Libraries has a digital version that you can download if you are part of a university that is affiliated with them (though its quality is sometimes unreadable), and I’ve had a digital copy for a long time now as a result. The 1977 microfilm version was missing several important volumes, however, including the entire book on the gaseous diffusion project, a volume on the acquisition of uranium ore, and many technical volumes and chapters about the work done at Los Alamos. All of this was listed as “Restricted” in the guide that accompanied the 1977 version.

I was talking with Bill Burr of the National Security Archive sometime in early 2013 and it occurred to me that it might be possible to file a Freedom of Information Act request for the rest of these volumes, and that this might be something that his archive would want to do. I helped him put together a request for the missing volumes, which he filed. The Department of Energy got back pretty promptly, telling Bill that they were already beginning to declassify these chapters and would eventually put them online.

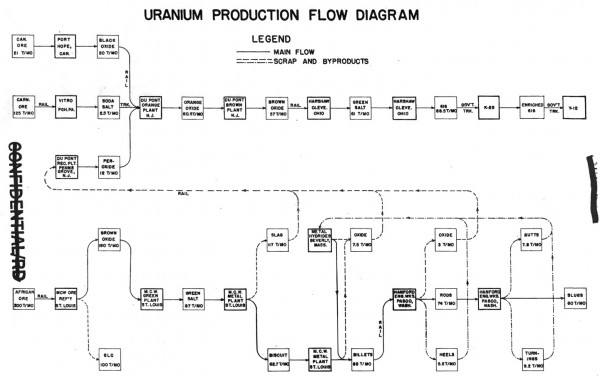

Manhattan Project uranium production flow diagram, from Manhattan District History, Book 7, “Feed materials.”

The DOE started to release them in chunks in the summer of 2013, and got the last files up this most recent summer. You can download each of the chapters individually on their website, but their file names are such that they won’t automatically sort in a sensible way in your file system, and they are not full-text searchable. The newly-released files have their issues — a healthy dose of redaction (and one wonders how valuable that still is, all these years — and proliferations — later), and some of the images have been run through a processor that has made them extremely muddy to the point of illegibility (lots of JPEG artifacts). But don’t get me started on that. (The number of corrupted PDFs on the NNSA’s FOIA website is pretty ridiculous for an agency that manages nuclear weapons.) Still, it’s much better than the microfilm, if only because it is rapidly accessible.

But you don’t need to do that. I’ve downloaded them all, run them through a OCR program so they are searchable, and gave them sortable filenames. Why? Because I want people — you — to be able to use these (and I do not trust the government to keep this kind of thing online). They’ve still got loads of deletions, especially in the Los Alamos and diffusion sections, and the pro-Groves bent to things is so heavy-handed it’s hilarious at times. And they are not all necessarily accurate, of course. I have found versions of chapters that were heavily marked up by someone who was close to the matter, who thought there were lots of errors. In the volumes I’ve gone the closest over in my own research (e.g. the “Patents” volume), I definitely found some places that I thought they got it a little wrong. But all of this aside, they are incredibly valuable, important volumes nonetheless, and I keep finding all sorts of unexpected gems in them.

You can download all of the 79 PDF files in one big ZIP archive on Archive.org. WARNING: the ZIP file is 760MB or so. You can also download the individual files below, if you don’t want them all at once.

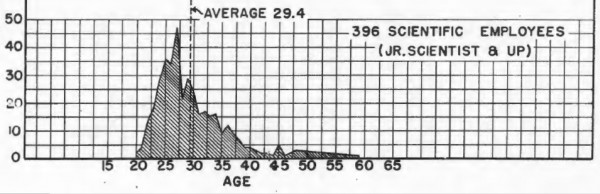

Statistics on the ages of Los Alamos employees, May 1945, from the young spy, Ted Hall (19), to the old master, Niels Bohr (59). From Manhattan District History, Book 8.

What kinds of gems are hidden in these files? Among other things:

- The total number of people who worked on the Manhattan Project — over half a million!

- Impressive flow-charts showing how uranium ore moved throughout the project.

- A crazy drawing of the Calutron process labeled “Dante’s Inferno”!

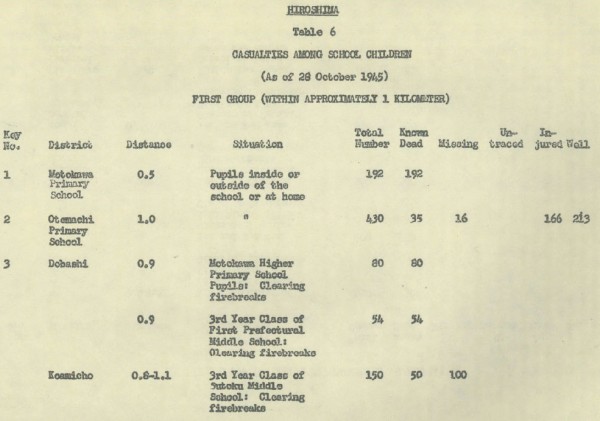

- Some pretty vivid firsthand accounts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from the Manhattan Project scientists who visited them.

- Tons of fascinating statistics. Want to know the distribution of ages amongst Los Alamos scientists? We’ve got that — from Ted Hall (age 19) to Niels Bohr (age 59).

- Pretty interesting statistics about the number of fatalities on the project — as you would expect from a project of such size, whose primary employment was construction, a lot of people got injured or died over the course of it, mostly from mundane (non-nuclear) accidents. There’s something comically tragic about working on the project to build the first atomic bomb and getting run over by a tractor.

- A somewhat incredible account of a non-fatal criticality accident early on at Los Alamos: “No ill effects were felt by the men involved, although one lost a little of the hair on his head.”

- Security forms, security guides, security pamphlets — lots of original documents and details that otherwise would have been pretty easily lost in the vastness of the archives. One of my favorites: a declaration of secrecy signed by scientists on the project in which they swear upon the sanctity of their scientific reputation!

And a lot more. As you can see, I’ve drawn on this history before for blog and Twitter posts — I look through it all the time, because it offers such an interesting view into the Manhattan Project, and one that cuts through a lot of our standard narratives about how it worked. There are books and books worth of fodder in here, spread among some tens of thousands of pages. Who knows what might be hidden in there? Let’s shake things up a bit, and find something strange.

Below is the full file listing, with links to my OCR’d copies, hosted on Archive.org. Again, you can download all of them in one big ZIP file by clicking here, (760 MB) or pick them individually from below. Items marked with an asterisk are, as far as know, wholly new — the others have been available on microfilm in one form or another since 1977. Read the full post »