What a long set of weeks it has been! On top of my usual teaching load (a few hours of lecture per week, grading, etc.), I have given two public talks and then flown to Chicago and back for the annual History of Science Society meeting. So I’ve gotten behind on the blog posting, though I have more content than usual for the next few weeks built up in my drafts folder, without time for me to finish it up. During this busy time, by complete coincidence, I also got briefly interviewed for both The Atlantic (on plutonium and nuclear waste) and The New York Times (on the apparent virality of nuclear weapons history).

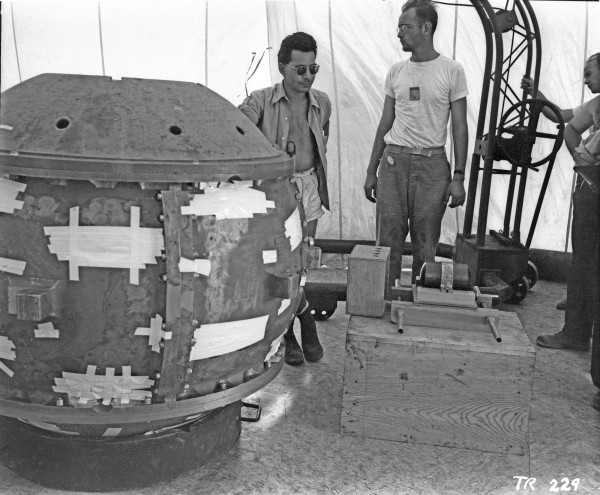

Louis Slotin and Herb Lehr at the assembly of the Trinity “Gadget.” Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory Archives, photo TR-229.

The Times article had a phrase in it that has generated a few e-mails to me from a confused reader, so I thought it was worth clarifying on here, because it is actually an interesting detail. It is one of those funny phrases that if you knew nothing about the bomb you’d never notice it, and if you knew a good deal about the bomb you’d think it was wrong, but if you know a whole lot more than most people care to know unless they are serious bomb nerds you actually see that it is correct.

Here’s the quote:

First, he glanced at the scientists assembling what they called “the gadget,” a spherical test device five feet in diameter. Then, atop a wooden crate nearby, he noticed a small, blocky object, nondescript except for the role he suddenly realized it played: It was a uranium slug that held the bomb’s fuel. In July 1945, its detonation lit up the New Mexican desert and sent out shock waves that begot a new era.

I’ve added emphasis to the part that may seem confusing. The Trinity “Gadget” and the Fat Man bomb, as everyone knows, were fueled by fission reactions in a sphere of plutonium. The Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima, by contrast, was fueled by enriched uranium. So what’s this reference to a uranium slug inside the Trinity Gadget? Isn’t that wrong?

Detail from the above photo showing the tamper plug cylinder. Inset is a rare glimpse of what the tamper probably looked like, taken from a different Los Alamos photo related to Slotin’s criticality accident. (It is in the middle-right of the linked photo. Yes, I cop to spending time searching the edges of photos like this…) You can see how the tamper plug, rotated, would be inserted into the middle of the tamper sphere.

Perhaps surprisingly — no, it’s not. There was uranium inside both the “Gadget” and Fat Man devices — in the tamper. The tamper was a sphere of uranium that encased the plutonium pit, which itself encased a polonium-beryllium neutron source, Russian-doll style. Here uranium was chosen primarily for its physical rather than its nuclear properties: it was natural, unenriched uranium (“Tuballoy,” in the security jargon of the time), and its purpose was to hold together the core while the core did its best to try and explode. (It also helped reflect neutrons back into the core, which also worked to improve the efficiency.)

The inside of an exploding fission bomb can be considered as a race between two different processes. One is the fission reaction itself, which, as it progresses, rapidly heats the core. This heating of the core, however, causes the core to rapidly expand — the core is trying to blow itself apart. If the core expands beyond a certain radius, the fission chain reaction stops, because the fission neutrons won’t find further plutonium nuclei to react with. If you are a bomb designer, and want your bomb to have a pretty big boom, you want to hold the bomb core together as long as possible, because every 10 nanoseconds or so you can hold it together equals another generation of fission reactions, and each generation releases exponentially more energy than the previous.

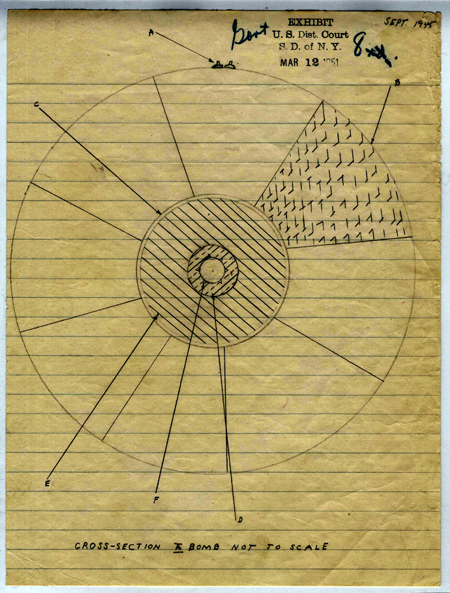

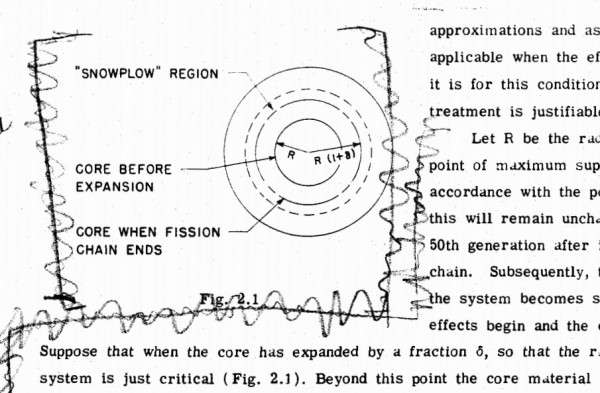

An image that somewhat evokes how bomb designers talk about the dueling conditions inside of the bomb, when they are talking to each other. The “snowplow region” is where the expanding bomb core runs into the tamper and is compressing it from the inside. This is a level of bomb design that I would have normally assumed would be classified but it has been very clearly declassified here, so I guess not. From Glasstone, “Weapons Activities of Los Alamos, Part I” (see footnotes).

So in the Fat Man and Trinity bombs, this is accomplished with a heavy sphere of natural uranium metal. Uranium is heavy and dense, and the process of making plutonium and enriched uranium required the United States to stockpile thousands of tons of it, so the relatively small amount needed for a tamper was easily at-hand. It makes a good substance with which to try and hold an exploding atomic bomb together. The Little Boy bomb, as an aside, used a tungsten tamper, for some reason (maybe to avoid excessive background neutrons, I don’t know).

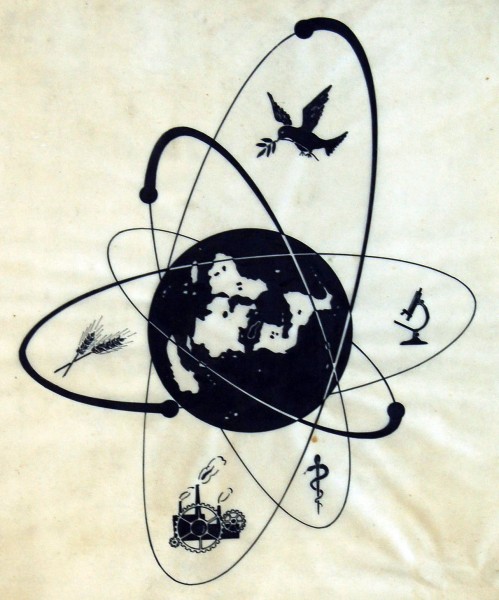

Now to add one more little bit of detail: we tend to think of the Trinity/Fat Man implosion bombs as just being a set of spheres-inside-spheres. This is a convenient simplification of the actual geometry, which had other factors that influenced it. The tamper, for example, was not just two halves of a hollow sphere that could fit together. Rather, it was more like a solid sphere out of which a central cylinder had been removed. The cylinder was known as the “tamper plug,” and was itself made of two halves that, when assembled, had room for the plutonium pit inside of them.

Why do it this way? Because the scientists and engineers wanted to be able to insert the fissile pit portion into the bomb as one of the final additions. This makes good sense from a safety point of view — they wanted it to be relatively easy to add the final, “nuclear” component of the bomb and to keep it separate from the non-nuclear components (like the high explosives) as long as possible. I don’t want to over-emphasize the “ease” of this operation, because it was not a quick, last-minute action to put the pit inside the bomb. (Some later bomb designs which featured in-flight core insertion were designed to be just this, but this was some years away.) It was still a tetchy, careful operation. But they could assemble the entire rest of the tamper, pusher, and high explosives, then remove one layer of high explosives, remove the top of the pusher, and then lower the tamper plug (with pit) into the center, then replace all of the other parts, hook up the detonators and electrical system, and so on.

A rendering I made in Blender to illustrate the principle here. The pit and initiator are inside of the plug (expanded at right), which is then sealed into a cylinder and inserted into the tamper sphere at the center of the bomb. The tamper is itself embedded in a boron shell which is inside of an aluminum shell which is inside of the explosive lenses which is inside of the casing. This is part of a modeling/visualizing project I’ve been working on for a little while now and will post more on at a future date. The dimensions are roughly correct though there are still many simplified detail (e.g. exactly how the plug fits together — there were uranium screws!).

So when John Coster-Mullen describes, as in the previously-quoted New York Times article, finding a picture of the tamper plug, it’s kind of a cool thing. There’s only one picture that shows it (the one at the beginning of this post), and it is one of those things that you don’t even usually notice about that picture until someone points it out to you. I never noticed it until John pointed it out for me, even though I’d seen the picture many times before. Usually one’s attention is drawn to the Gadget sphere itself, and the people standing around (including Louis Slotin, who would later be killed by playing with a core). It’s kind of surprising it was declassified, since the length of the tamper plug is the diameter of the tamper, and the width of the plug is just a little bigger than the diameter of the plutonium core. The US government usually doesn’t like to reveal, even inadvertently, those kinds of numbers.

There is also one little fact about the natural uranium in the Gadget and Fat Man bomb that is not well appreciated, and I didn’t appreciate well until reading John’s book. (Which I have heard people say is rather expensive for a self-published production, but if you’re a serious Manhattan Project geek it is hard to imagine how you’d get by without a copy of it — it is dense with technical details and anecdotes. It is one of the only books that I don’t often bother to put back in the bookcase because I end up needing to reference it every week or so.)

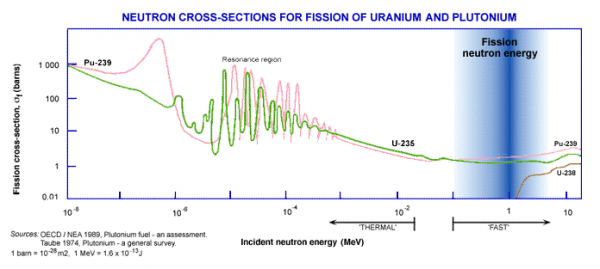

Neutron cross-sections for the fissioning of uranium and plutonium. The higher the cross-section, the more likely that fission will occur. The indicated “fission neutron energy” means that that is the approximate energy level of neutrons released from fission reactions. So you can see why, in a reactor, those are slowed down by the moderator to increase the likelihood of fissioning. In a bomb, there is no time for slowing things down, so you need fissile material in much higher concentrations. Source: World Nuclear Association.

In talking about which elements are fissile — that is, can sustain a nuclear fission chain reaction — technical people tend to talk about neutron cross sections. This just means, in essence, that the likelihood of a giving elemental isotope (e.g. uranium-235, plutonium-239) undergoing fission when encountering a neutron is related to the energy of that neutron. At the size of neutrons, energy, speed, and temperature all considered to be the same thing. If you look at a neutron cross section chart, like the one above, you will see that uranium-235 has a high likelihood of fissioning from slow neutrons, and a low-but-not-zero likelihood of fissioning from faster neutrons. You will also see that the neutrons released by fission reactions are pretty fast. This is why to sustain a chain reaction in uranium you either need to slow the neutrons down (like in a nuclear reactor, which uses a moderator to do this), or pack in so many U-235 atoms that even the low probability of fissioning from fast neutrons doesn’t mean that a chain reaction won’t happen (like in a nuclear bomb, where you enrich the uranium to be mostly U-235).

Still with me? If you look a little further on the graph, you’ll see that uranium-238 also has a possibility of fissioning, but it is a pretty low one and only even becomes possible with pretty fast neutrons. This is why, in a nutshell, that unenriched uranium can’t power an atomic bomb by itself: it is fissionable but not fissile, because it can’t reliably take fission neutrons and turn them into further fission reactions. But people who have studied how thermonuclear weapons are used know that even uranium-238 can contribute a lot of explosive energy, if it is in the presence of a lot of high-energy neutrons. In a multistage hydrogen bomb, at least 50% of the final explosive energy is derived from the fissioning of U-238, which is made possible by the high-energy neutrons produced from the nuclear fusion stage of the bomb (which itself is set off by an initial fission stage). The neutrons produced by deuterium-tritium fusion are around 14 times more energetic than fission neutrons, so that lets them fission U-238 easily. From the cross-section chart above, you can see that U-238 fissioning can happen from fission neutrons, but only if they happen to be pretty high energy to begin with and stay that way. In practice, neutrons lose energy rather quickly. Still, according to a rather sophisticated analysis of the glassified remains of the Trinity test (“Trinitite”) done a few years back by the scientistsThomas M. Semkow, Pravin P. Parekh, and Douglas K. Haines, a significant portion of the final fissioning output at Trinity (and presumably also Nagasaki) came from the fast fissioning of the tamper, with some of that energy released from the U-238 fissioning.

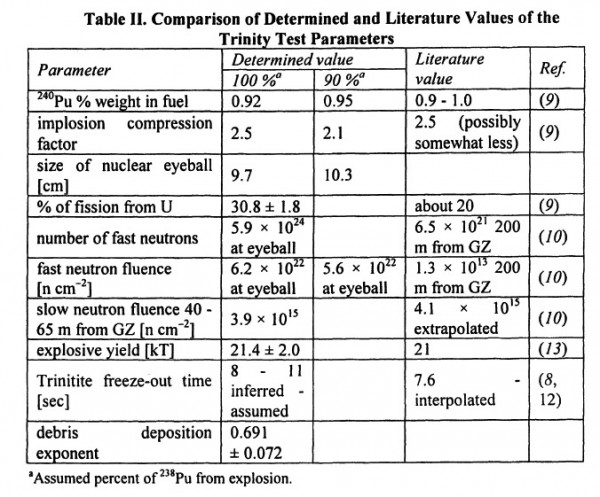

For the hardcore bomb geeks, here is a sort of “conclusion table” from the Semkow et al. article. Note that they calculate at least 30% fissioning from uranium, and give some indication the amount of compression of the core, the number of neutrons created, and so on. Their terminology of the “eyeball” is taken from Richard Rhodes, who uses the term in passing in The Making of the Atomic Bomb, and refers to the confined area where the fission chain reaction is taking place.

How significant? Semkow et al. calculate that about 30% of the total yield of the Trinity test came from fissioning of the uranium tamper, which translates to about 6 kilotons of energy. If they had made the tamper out of tungsten (as was the Little Boy tamper), then the total yield of the Gadget would have only been around 14-15 kilotons — not that different from Little Boy (which was ~13-15 kt). And presumably if the Little Boy bomb had used a uranium tamper, assuming that didn’t cause problems with the design (which it probably would have, otherwise they probably would have used one), it would have had the same yield. (This doesn’t mean that Little Boy wasn’t, in fact, horribly inefficient — it got about the same yield but it required 10X the fissile the material to do so!) The total mass of the tamper was around 120 kg of natural uranium, so if it contributed 6 kilotons of yield that means around 350 grams of the tamper underwent fission, and that is about 0.3% of the total mass.

So the fact that Trinity and Fat Man had uranium inside of them is already kind of interesting, but the fact that a large portion of the blast derived from that uranium is sort of a neat detail. Why don’t we generally learn about this? It isn’t that it is so terribly classified, per se, but it does require a lot of detailed explanation, as evidenced by the length of this post. We tend to abstract the mechanics of the bombs for explaining their conceptual role, and explaining the basic concepts of how they work. I have no problem with this, personally, because hey, let’s be honest, the exact amount of energy derived from different types of fissioning in the bombs is a pretty wonky thing to care about! But every once in awhile you need to understand the wonky things if you want to talk about, say, what that funny little “plug” is in the top-most photograph, and its role in the bomb. I suppose one of the points of the phenomena described by the Times article, where the geek population on the Internet is providing a newfound audience to Manhattan Project details, is that these sorts of wonky aspects are no longer limited to people like John Coster-Mullen, Carey Sublette, or myself. There are some people who might see this focusing on the technical details as missing the broader picture. I don’t happen to think that myself — much of the broader picture is in fact embedded in the technical details, and “new” discussions of technical details are one way of shaking people out of the calcified narratives of the Manhattan Project, something which, as we approach the 70th anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, seems to me a valuable endeavor.