A lot of people have been passing around the latest news story about the supposed “Nazi nuclear bunker” that was supposedly discovered in Austria. Normally I would not comment at length about such a thing, originating from tabloids and so obviously (to my eye) devoid of serious merit. But since the passing around has even made it to more austere publications (like the Washington Post) and because a number of people have asked me informally what I thought about it, I thought I could take it as an opportunity to talk about what bad history of the bomb looks like.

Cheryl Rofer has compiled some of the basics of the story on Nuclear Diner. The basics are this: an Austrian filmmaker named Andreas Sulzer has been trying to make a film about an Austrian bunker that dates from World War II. He has been claiming there was a nuclear connection to this bunker, and gotten some headline-grabbing tabloid stories about it, since 2013. What’s the evidence for it being a nuclear site? He claims that he has an American intelligence document from 1944 that lists it as a site of possible interest. He has made vague claims about radioactivity. It is part of an existing weapons production plant (a factory that produced rocket engines). Some physicists might have been sent there. Did we mention there was a bunker?

Yeah. That’s it. This stuff is pretty obviously thin, but let’s just say: Allied intelligence about German nuclear sites in 1944 was poor and scattered and means nothing. Radiation is everywhere and can fluctuate from a variety of natural and artificial sources — only by talking about levels of radiation do we start to wonder if something unusual is occurring, and only by talking about specific radioactive isotopes can we start to really wonder if any given radiation is of interest to us or not. (This is not hard to do — there are hand-held devices that can both measure radiation intensity and determine the isotopes in about 30 seconds, these days. ) The fact that it is part of an existing plant is probably evidence against it being a super-secret nuclear installation (compartmentalization). And physicists were involved in practically every technical program during World War II, so their presence tells us nothing one way or the other.

The obvious thinness of this evidence, and the obvious motivation of the filmmaker — who has been denied a permit to dig around the site — should already be a sign to any self-respecting journalist that this is not worth touching. Certainly not without talking to some other experts about it. The only person anyone seems to have called up is Rainer Karlsch, whose own work on the German nuclear program is extremely controversial (Karlsch claims the Germans detonated some kind of dirty bomb or pure-fusion bomb — also on very thin evidence). For all of his outsized claims, at least Karlsch did his homework and tries to marshall evidence for his work. I don’t think Karlsch’s evidence fits the strength of his claims, and there are real technical problems with Karlsch’s reasoning, but there is at least a serious scholarly discussion to be had there. There is not one to be had (at least, not yet) about the Sulzer claims, because there is no there there. Karlsch’s only quoted comment is that he thinks the Germans got further along with their nuclear program than most people think (to be addressed below), and doesn’t comment on the Sulzer claims at all — which makes it not really a supporting comment for Sulzer at all.

But if you slap “Nazi” and “nuclear” onto something, it gets a lot of hits, and that’s what appears to be the motivation here both for the Sunday Times and the many other sources that have picked up the same story and run it without checking in with anybody else to see whether it is even plausible. Which is a sad state of things.

There is a bunker. No credible evidence has actually been offered to make one think it has a nuclear connection. That the Germans had large underground bunkers for technical projects is well-known — that they had them for their nuclear program is not, because there is no evidence of this. (They did do some reactor work in some caves towards the end of the war, but it was small scale.) Newspapers should stop passing this kind of nonsense around… especially since it is not even “news” at this point — the bunker story has been circulating for over 2 years, without any additional increase in credibility!

About two or three times a year I get contacted by people who are working on things relating to the German or Japanese wartime nuclear programs. The appeal is obvious: there is a built-in audience for this kind of thing, and there are still areas of uncertainty with regards to these programs. I have written on here in the past on a few of the questions I’ve stumbled into with regards to the German program, for example. We don’t know everything about these programs, and there are reasons to think that there is still more to learn. So I’m always willing to engage with people on these questions.

At least the Washington Post hedged the headline a bit, “says he uncovered.” Still misleading, but makes the factual basis a little more clear.

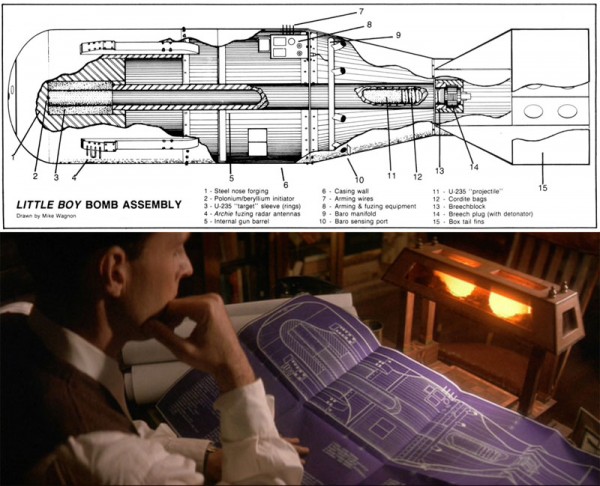

Some of the stuff strikes me as improbable or a little crack-pot-ish; some of it seems plausible and interesting. I’m a firm believer in the idea that sometimes non-academic historians stumble onto interesting things and interesting questions (John Coster-Mullen is a great example of this), and I don’t discriminate unless people show themselves to be going down truly untenable paths (like that small segment of the Internet who believes that all nuclear weapons are a hoax, which is just a truly silly “theory”). I will hear just about anyone out, and tell them what I find plausible or implausible about their ideas. I am a skeptical person — big claims need big evidence. But I do believe there is still a lot “out there” to be found on these topics, and maybe more than a few surprises yet.

The German nuclear program seems to attract a lot of “theorizing” in particular, ranging from the “they got further in it than most people think” (which is an easy argument to make since most people don’t know much about the German program at all) to the absurd extremes of “they made an atomic bomb and the only way the Americans got one themselves was by stealing it” (conspiracy country).

The 1945 version of the same headline — New York Herald Tribune, August 8, 1945, story about the Norsk Hydro plant, which also over-emphasized the closeness of Germany’s getting the bomb for dramatic effect. Click the image to read the article.

Public understanding of the German nuclear program is indeed a confused and often incorrect thing, owing to a history of the politicization of the topic. In the very early days after the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the “race with the Germans” narrative was played up very heavily by the Manhattan Project public relations people, both because it made for good drama and because it seemed to justify the US interest in the topic. And, indeed, the scientists who lobbied for the atomic bomb program between 1939 and 1944 or so did believe that the Germans might be ahead of them and that they were “racing” them to make the atomic bomb. It was not until late 1944 that the Alsos program reported back that the Germans had never gotten very far with their work, and that the US had never really been “racing” with them at all. Even today, though, we still see the legacy of this, with television programs and movies over-dramatizing the closeness of the “race,” and the importance of things like the sabotage of the Norsk Hydro facility, all of which makes it look like the Germans were very close indeed.

On the other side of the coin, we also have things like the Copenhagen play, which is an excellent piece of drama (and I am indeed a fan) but has infected a new generation with the idea that the Germans made no progress at all with regards to nuclear weapons — and indeed, had never even seriously considered the matter — because Heisenberg had consciously sabotaged the whole project. Never mind that Heisenberg’s own claims were far more nuanced on this point (he was always vague on this, only implying in a round-about way that they might not have made a bomb because they didn’t really want one). The play and the press around it has led a lot of people to think that the Germans knew really nothing about nuclear weapons development, and that they had intentionally avoided making them.

Allied troops disassembling the German experimental research reactor at Haigerloch, as part of the Alsos mission.

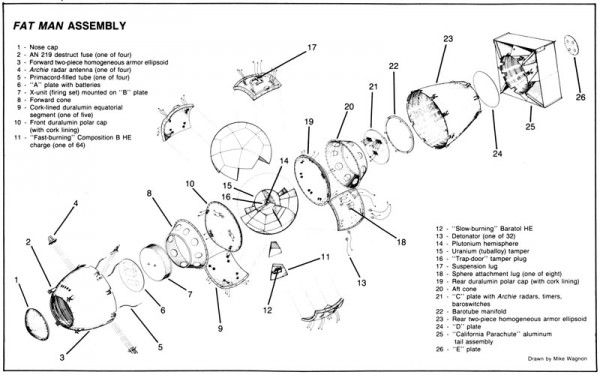

The truth, so far as we know it now, is somewhere other than these two extremes. Mark Walker’s two books (German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-1949 and Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, And The German Atomic Bomb) are still excellent, though a bit more has come out since then. The basic gist of Walker’s work is that the German program knew a lot on paper, but never quite crystallized everything organizationally or technically to keep their program from being anything more than a side-project, focused primarily on reactor development. They never developed large-scale isotopic enrichment facilities, and they never got a reactor that went critical. Their reactor work was sophisticated given the conditions under which it was being done, but it never achieved criticality. Some members of the various teams that worked on the project had some fairly accurate understandings of how a nuclear weapon might be made, but there was also a lot of confusion circulating around (some members of the team understood it would be a fast-neutron fission reaction in enriched material, some were confused and focused on it being basically an out-of-control pile). Some were considering rather advanced designs (Karlsch has convinced me that they thought a bit about implosion, for example), but the whole thing was mostly a exploratory program.

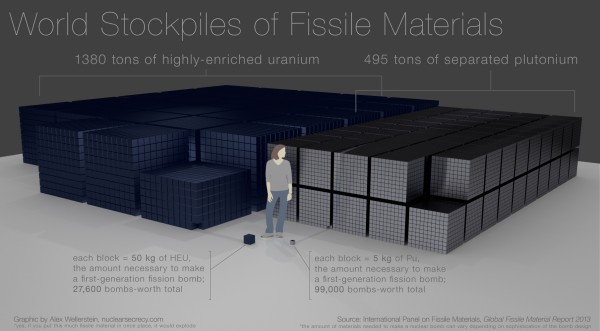

The plausibility of any new arguments about German successes with their nuclear programs is always limited in part by what we know about the technical requirements of such an endeavor. The Manhattan Project need not be the only model of a successful nuclear program (it was in many ways unusual), but it does provide some baseline metrics for talking about nuclear programs of the 1940s. Any successful plutonium-breeding program is going to require fairly large reactors, because plutonium reprocessing extracts only grams of “product” from each ton of uranium fuel that goes into it. (Each of the three early Hanford reactors extracted only 225 grams of plutonium from every ton of uranium processed.) Any successful isotopic-enrichment program is going to require huge feed supplies of uranium (the Manhattan Project approaches consumed thousands of tons of uranium), pretty large facilities, and a lot of electricity.

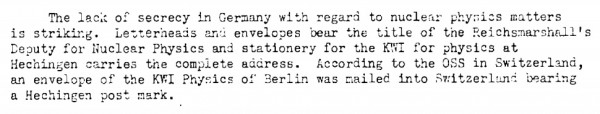

When Alsos leader Sam Goudsmit was investigating the Germany nuclear work, he was struck by how little of it was kept very secret — evidence, in his mind, that they had not gotten very far with it. (S.A. Goudsmit and F.A.C. Wardenburg, “TA-Straussburg Mission,” (8 December 1944), copy in the Bush-Conant file, Roll 1, Target 6, Folder 5.)

Separate from the technical argument is a bureaucratic one — if the Germans supposedly made such progress, why is was there no organizational evidence of it in the copious reports, papers, formal and informal statements, and so on that were discovered by the Alsos project, later researchers, and at Farm Hall? Big programs leave big traces. If one wants to claim that the German program was big, one has to show where those traces are, or come up for a plausible argument for why there are no traces.

This does not mean that one might not find more evidence in the future. It just means that any claims and evidence need to fit within the existing technical and bureaucratic narratives. For example, one could argue, “oh, but they did have a massive isotopic enrichment plant, and it was here, and here is evidence of — if one had the evidence. On the bureaucratic side, one could argue that people who we previously thought were important in the program (e.g. Gerlach) were actually out of the loop entirely. Or something along those lines.

But you can’t just find a hole in the ground and say, “ah, here is where Hitler was making a bomb.” Aside from the implausibility of a nuclear program existing in a single underground bunker, by itself this kind of claim hasn’t done the work to be plausible. At best, if done in good faith, it is a claim along the lines of “oh, maybe this is worth looking into more.” That is fine — hey, I’d even nominally support that — but one shouldn’t be going to the newspapers about it at that stage, and the newspapers shouldn’t be passing off your claim as having more validity than half of the other implausible claims that circulate around these topics. This is premature, and the net effect is going to be misleading for the readership.

As historians, we need to be open to the idea that there are still mysteries to be solved, secrets to be unearthed, even about ground that superficially looks well-trodden. But I wish journalists would do a little better than just re-printing the overblown claims of unreliable sources, without checking with experts on their plausibility. Couching it as, “this guy made a claim” doesn’t get you off the hook, because we all know that only the initial, big-claim story is the one that will be passed around, and that almost nobody will notice when no follow-ups occur, or the mild “so no evidence turned up for this guy’s big claim” story comes out.

Journalists — You can do better!

!["Nuclear C3 [Command, Control, Communication] Transport Systems" — an attempt to characterize the technical, organizational, and political systems needed to actually start nuclear war in the United States today. Source: The Nuclear Matters Handbook, by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs.](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Nuclear-C3-Transport-Systems-600x450.jpg)