Oak Ridge, Tennessee, has the dubious honor of having been one of the few places in the United States that qualified for the label of “secret city.” What we usually have in this country are secret sites, but Oak Ridge was more than a site. During World War II, Oak Ridge had a population of 75,000 people, making it the fifth largest city in the state — one that didn’t appear on official maps.

The Department of Energy has recently been digitizing a large number of photographs of life at Oak Ridge, and it seemed like a good time to talk about the place. I would be remiss not to send interested readers to Frank Munger’s Atomic City Underground, which is a site that lives and breathes Oak Ridgery seven days a week. Some of my favorites from the new photos:

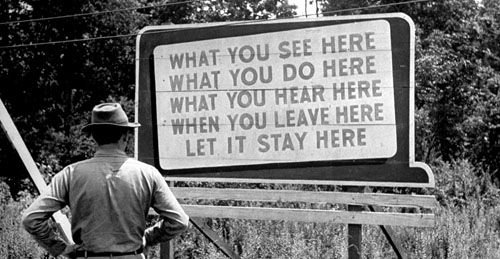

- A very cryptic security billboard from 1970. An eclipse? The moon? What does it mean?

- A handshake in from an Atoms for Peace emblem that has seen better days. (Perhaps I should say, a godawful Atoms for Peace emblem.)

- Santa and his Irish elves.

- Cool dog. (I like cool dogs.)

- There are atoms in your autos! But the kids don’t look that convinced.

- The Atoms for Peace van. Great for cross-country trips. Compare with the more touchy-feely ERDA truck.

- “Oak Ridge Needs Centrifuges.” (That’s what they all say.) But also check out the seal of the City of Oak Ridge, on the podium.

- Ed Westcott, the Oak Ridge photographer, testing a strobe light.

Oak Ridge was big for a secret city. Even the presence of “secret cities” or secret sites on a massive scale were pretty novel for the United States at the time. The only pre-World War II analog that I’ve come across is the lewisite (chemical gas) production facility during World War I known as “the Mousetrap” (once you enter, you never leave), where James B. Conant (future atomic administrator) worked as a young chemist.1

Most of the personnel at Oak Ridge were in construction of some sort. It’s easy to see why, when you look at what they made there. The job of producing fissile material (enriching uranium, in this case) was mostly a construction job. No shock, then, that it was the Army Corps of Engineers who were called in to run the project in 1942, and that the guy they chose to head the whole project (Gen. Leslie Groves) had recently constructed the Pentagon — still the world’s largest office building by area. I like to point out to students that all of the world’s nuclear fission research in 1938 could fit onto an average-sized dinner table; in less than a decade, it spanned an entire country.

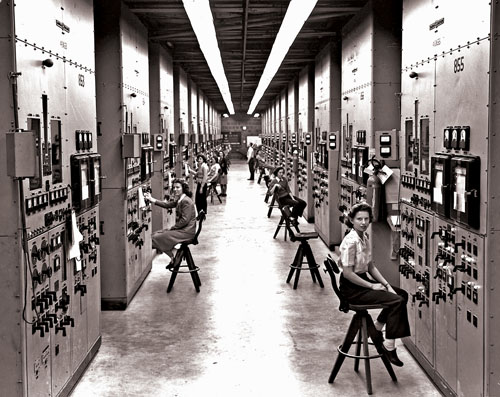

The K-25 gaseous diffusion plant, at the time the largest single factory under one roof in the entire world.

The level of secrecy and compartmentalization at Oak Ridge created a number of practical problems for those running the site. It wasn’t just that Oak Ridge was cut off from the outside world, which it was. It was also cut off from the rest of the Manhattan Project, kept under tight compartmentalization restrictions.

The vast majority of those working at Oak Ridge during the war had no idea what they were working on. They knew it involved building very large facilities, that there were various health hazards involved, and that supposedly it was an important war project. All of those who were there thought they had signed up to do their part, yet the war in Europe seemed to end without any intervention on their part.

The National Archives has a great transcript of a radio show from 1947 that sheds a lot of interesting light on what it was like for your average technician to work at Oak Ridge. Here’s a quote from George Turner, who apparently managed workers:

Well it wasn’t that the job was tough… it was confusing. You see, now one knew what was being made in Oak Ridge, not even me, and a lot of the people thought they were wasting their time here. It was up to me to explain to the dissatisfied workers that they were doing a very important job. When they asked me what, I ‘d have to tell them it was a secret. But I almost went crazy myself trying to figure out what was going on. One man came up to me and said, “I thought this was a war job.” “It is,” I said. He looked at me very unbelieving. “Well I’ve been here two months now,” he stated, “And I’ve been watching those two smoke stacks outside every day, and no smoke has ever come out of them… There’s something funny going on around here and I’m getting out.”

The smoke stacks, it goes on to explain, were intake stacks, pulling fresh air in to the plant. It also describes how the railroad cars full of freight — uranium — always left empty, another suspicious looking thing.

Rumors abounded about what the plant was meant to accomplish, both inside and outside of it. These rumors were, of course, carefully cataloged by Manhattan Project security officials. The most amusing one I’ve come across for Oak Ridge was that it was actually a model socialist community being created by Eleanor Roosevelt as a prototype for future Communist domination of the United States. Nothing encourages nonsense like a vacuum of information.

Here’s Mary Anne Bufard’s perspective of being one of these compartmentalized workers:

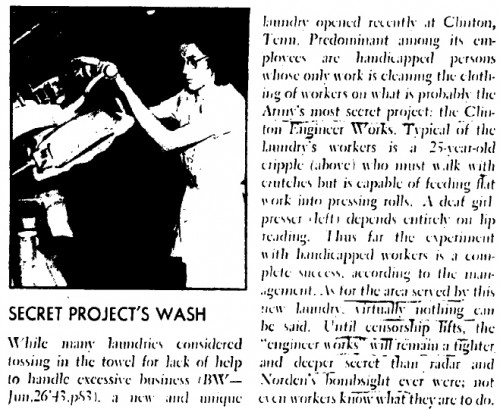

It just didn’t make any sense at all. I worked in the laundry at the Monsanto Chemical Company, and counted uniforms. I’ll tell you exactly what I did. The uniforms were first washed, then ironed, all new buttons sewed on and passed to me. I’d hold the uniform up to a special instrument and if I heard a clicking noise — I’d throw it back in to be done all over again. That’s all I did — all day long.

Everyone reading this today knows immediately what she was doing: screening for radiation. But she didn’t learn about that until after the bomb was used, and didn’t realize how important the job actually was. From her perspective, it was just a strange laundry procedure — and a dull one, at that.

Interestingly, the story of Oak Ridge’s laundry was leaked during the war to Business Week. An article from 1943, described the “Secret Project’s Wash,” calling attention both to the fact that many handicapped laborers were used for the laundry service, and that the project was “probably the Army’s most secret project.” James B. Conant forwarded the above on the General Groves in August 1943; Groves replied that, “We have taken steps but the press must remain free and untrammeled.”2

From the radio program again, here’s Bill Ragan’s perspective, working in the plants themselves:

For three years I worked in the Carbide and Carbon Chemical Company Plant where they put me in a room with about 50 or 60 other guys. I stood in front of a panel board with a dial. When the hand moved from zero to 100 I would turn a valve. The hand would fall back to zero. I turn on another valve and the hand would go back to 100. All day long. Watch a hand go from zero to 100 then turn a valve. It got so I was doing it in my sleep.

The plant Ragan described was probably K-25, the gaseous enrichment facility. I’m not totally sure what he’s describing doing, but it sounds like he was pressurizing a chamber, evacuating it, pressurizing it again. There were similar boring jobs at the electromagnetic (Calutron) enrichment facility, where women technicians would manually help to focus the ion beams. Tedious work.3

As mentioned, all of this secrecy created tremendous morale problems. The job was boring. The purpose was unknown. The staff sizes were huge. What’s an administrator to do?

One of the most amazing documents I’ve come across in my work is a report that NARA has put online from the “Recreation and Welfare Association of Oak Ridge.” The problem was secrecy; the answer was… sports.

The war worker in Oak Ridge, Tennessee has been working under some of the most unique working conditions ever known. Due to the secrecy surrounding the nature of the Project, he never saw the results of this labor. There was nothing in which he could take pride. Thus, one of the common incentives for work was not present. No sense of satisfaction could be realized in a job well done. Naturally, this created quite a problem of morale not commonly experienced. In seeking to cope with this condition, it was recognized that it was imperative that an extensive program of leisure-time activities be planned that would reach all possible interests.

A lot of sports. You’ll notice that many of those newly released Oak Ridge photos show baseball and football teams? Just the tip of the iceberg.

As part of their intermural sports program — designed to make the workers happy despite the secrecy-caused morale problems — Oak Ridge hosted (just to pick a few from the linked-to report):

- A baseball league with 10 teams.

- Badminton, shuffleboard, bowling, golf, tennis, and horseshoe tournaments.

- Hiking, casting, riding, roller-skating, and mini-golf clubs.

- 26 teams of touch football.

- 10 softball leagues with 81 teams. That’s a lot of softball!

Baseball for bombs. As I’ve said before, nuclear history can be wonderfully surreal.

Though the atomic bombs — and the subsequent publicity barrage — put Oak Ridge on the map for the first time (literally) in 1945, the entire city remained gated and “closed” until March 1949. Even after its gates were removed, of course, gates still surrounded the plants themselves, and it was still run by the Atomic Energy Commission until 1959.

Oak Ridge is still an odd place, a company town saddled with both a legacy of secrecy, labor disputes, and environmental harm. I’ve only had a chance to go there myself one time, but I was amazed by the existence of the Y-12 Federal Credit Union. Do other countries name their banks after facilities that produce weapons of mass destruction? Somehow I doubt it, but the nuclear world is strange enough that I try not to be surprised by anything.

- This period of Conant’s life is covered wonderfully in James Hershberg’s James B. Conant: Harvard to Hiroshima and the Making of the Nuclear Age (New York: Knopf, 1993), chapter 3. [↩]

- Note from James B. Conant to Leslie Groves, and Grove’s reply (3 and 24 August 1943), in Bush-Conant File Relating the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1940-1945, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, RG 227, microfilm publication M1392, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Roll 7, Target 10, Folder 75, “Espionage.” [↩]

- Why didn’t they automate this work? I suspect they would have loved to, but it would have taken extra time. Time was the one resource they lacked acutely at that point, and the only one they couldn’t bully out of other government hands. Three years ago I was called in as an expert on the PBS show History Detectives regarding an Oak Ridge patent that was developed towards the end of the war that would have automated the electromagnetic enrichment process. They don’t seem to have used this method (at least not at the time), but they were certainly thinking about the problem. [↩]

[…] I’ve already been engaged in some Oak Ridgery earlier in the week, I thought I might continue the trend. This week’s document is the transcript of a press […]

Dear Mr. Wellerstein,

I just happed along your website today and was excited to see some photos I have never seen before. Particularly the ones of my dad. Dad celebrated his 90th birthday last January.

DOE and The American Museum of Science and Energy gave him a big birthday bash.

There were so many people their you had to wait in line to get your photo taken with him.

Just this month Y-12 did a modern recreation of dads famous “Shift Change” photograph witch included dad. Every one had a great time.

I want to thank you for your inclusion of my dads work to your web site and we will look forward to new material.

Sincerely,

John Westcott

Thank you, John! I am honored to hear from you.

Why is K-25 still classified? Why so little information if they’re “taking it down”? My father, Robert M. Williams started there late 1943….passed away in 1961 due to multiple radiation exposures plus….

Y-12, X-10/ORNAL…tons of info plus pictures, names, activities, etc., but -0- on K-25. The people who worked there AND their families matter….

Thank you for your time. Hopefully, in my time, there will be lots of info and questions answered.

Sincerely,

Susie

[…] talked before about the concerns that project administrators had with respects to the demoralizing effect of […]

[…] as a sieve. It’s not a new thing, of course, and we’ve already seen a few historical examples of this on the […]

[…] because there was no real division between work and life at the Manhattan Project sites. (Even recreational sports were considered an essential part of the Oak Ridge secrecy regime, for example.) So we might isolate two separate narratives here — “secrecy is […]

“A very cryptic security billboard from 1970. An eclipse? The moon? What does it mean?”

One left field idea for the cryptic “security billboard” at Oak Ridge

http://www.flickr.com/photos/doe-oakridge/6925568294/in/photostream

comes from noticing that there is a dotted path from the earth to the moon on the billboard.

Hmmm, something travelling from the earth to the moon in 1970. I wonder what that could be? Any why would it involve Oak Ridge?

The thing that comes to mind is the Pu-238 in the radioisotope thermoelectric generator. The Apollo 12 through 17 missions carried SNAP-27 radioisotope thermoelectric generator to power the ALSEP experiments left behind on the moon. They couldn’t use solar power because the 14 day nights on the lunar surface would mean you’d need batteries to cover the time the sun was hidden (though not actually in eclipse).

Oak Ridge developed a techniques for making the Pu-238 pellets (they’re non-trvial … the pellet glows red hot) and encapsulating them in an iridium case so they can survey a rocket launch that goes bad or a rentry from space.

I would think at the height of Apollo people from Oak Ridge might be tempted to talk about “their contribution” to the mission. So in a way this billboard might be making an “in joke” (“you and I know what this means but the others don’t so let’s keep them in the dark”).

I’m not sure of the classification of RTGs, Pu-238 production and Oak Ridge but the DoE says “Oak Ridge National Laboratory developed and fabricated the material used to encapsulate the plutonium”. They also worked on nuclear reactors for space use too. I could imagine they they would be very useful for other secret missions e.g. powering a new generation of optical or radar reconnaissance satellites especially if they required high power or wanted to reduce footprint of the solar panels. Hence the secrecy?

The Nimbus 3 weather satellite (launch attempt in 1968 followed by successful launch in 1969) carried a RTG too (“to assess the operational capability of radioisotope power for space applications”). The RTG was recovevered from the first launch and reused in the second launch.

I don’t know why there is a clock face around the sun (though that looks a bit like RTG in cross section) and what (with the obviously incorrect orientation) “north arrow” means. Project names, maybe? Umbra? Eclipse? North something?

Still it’s a fascinating interesting of a cryptic security.

This is sort of related to cryptic project patches as documented by Trevor Paglen in his 2008 book I Could Tell You But Then You Would Have to be Destroyed by Me: Emblems from the Pentagon’s Black World. One interesting idea here is that sometimes the unit patches can leak information so they become even more cryptic (my favorite: all black with red lettering at the bottom “Si Ego Certiorem Faciam … Mihi Tu Delendus Eris”)

The Oak Ridge/NASA booklet “A Rough Road Leads To The Stars” details some of Y-12’s work on the Gemini and Apollo programs.

http://www.y12.doe.gov/library/pdf/about/history/info_materials/NASAbookletRev1.pdf

The Apollo Lunar Sample Return Container was made at Oak Ridge along with the Lunar Sample Bags and work on the TFE/FEP fluoropolymer (“Teflon”) they were made from.

Curiously there is no mention of RTGs or Oak Ridge design work on the Lunar Receving Laboratory vacuum system or science done lunar rocks so it’s not the whole story.

Is that limitation secrecy or just limiting the narrative for PR reasons? How can one tell?

[…] via The Nuclear Secrecy Blog […]

[…] and thereby not indicative of a weapons program. The assertion is irrelevant. If Iran opted to compartmentalize its nuclear weapons work like the United States did during the Manhattan Project, than Iranian […]