Plutonium is a fascinating element. It’s named after the Roman God of Death (by way of being named after a former planet). Its atomic abbreviation, “Pu,” was chosen to sound like “Peee-yooou,” as in, something smells bad. It doesn’t exist in nature (at least not in more than trace quantities) — all plutonium of significance currently in the world was created by human beings. And of course it is fissile, and so can be used as fuel for nuclear bombs or nuclear reactors.

It’s also pyrophoric, which is a fancy term to say it combusts on contact with air. It’s chemically unusual — it’s right on the juncture point between two different groups of elements, so it has six allotropic phases and four oxidation states. In non-sciency terms, this means that its volume and density changes radically as a factor of its temperature. This made it a tetchy addition to the wartime bomb project, where things like volume and density made a big difference when trying to use it inside of an exploding nuclear bomb. (They found that a plutonium-gallium alloy was a bit more stable.)

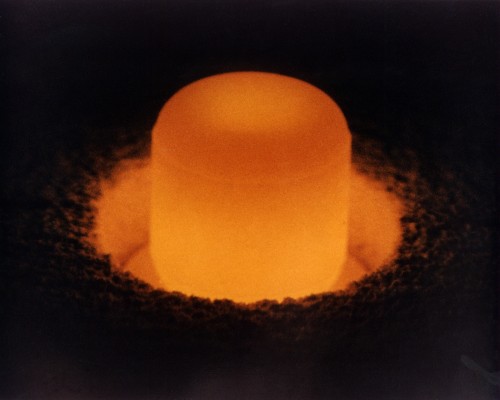

And hey, at least one form of it, Plutonium-238, actually glows in the dark! It does so because it’s radioactive enough to be scalding hot, which is why it is useful as a power source for things like the Curiosity rover currently tooling around Mars.1

If you’re something of a science geek, all of the above is, again, terribly fascinating. And I think it’s been established on here that I am, among other things, something of a science geek. There’s something alluring to folks like me about the idea of a chemically irritable, glowing man-made element named after the god of the dead that catches fire on its own and can be used to blow up entire cities. It sounds like something out of the worst types of science fiction, where authors just make up goofy substances to advance the plot.

Oh — I left out one key thing. It’s also toxic. Exactly how toxic is up for some debate — some informed sources say it is intensely, acutely toxic in very small inhaled amounts, others suggest its toxicity is a lot lower than that, making it more of a long-term threat — but either way, it’s not good for you if it gets into your body.

Because of its connections to nuclear weapons, the United States produced some 100 metric tons of plutonium over the course of the Cold War. And it was produced and operated on in big factories, under lots of secrecy, surrounded by lots of regular people. And there’s the rub: part of me wants to geek out on how awesome plutonium is, and part of me keeps saying, hey, idiot, don’t forget how it affects individual human beings — men, women, children, families. People who have been inadvertently exposed to it, for example. People who went out of their way to live next to a plutonium fabrication facility, for example, because it promised them good jobs and work that helped their country.

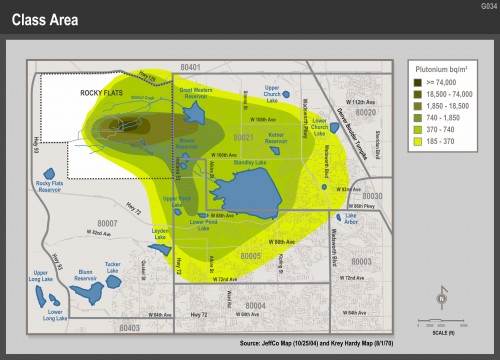

Map adapted from P.W. Krey and E.P. Hardy, “Plutonium in Soil around the Rocky Flats Plant,” HASL-235 (1970). This adaptation is taken from here.

I find nuclear history fascinating, from an intellectual point of view, and all of its little detailed ins and outs continually draw me in. But I endeavor to not be too fascinated by it — so attracted to the “technically sweet” bits that I lose sight of the big picture, and lose any empathy I might have with those who lived it. It’s all too common that in our rush for objectivity, especially about Big Male Military Subjects, that we take solace in the cold, hard facts, and disregard accounts that come from other perspectives.

I was reminded of this last week, when I went to see a talk at the National Museum of American History. The speaker was Kristen Iversen, talking about her new book, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats (which recently got a very favorable review from the New York Times). Iversen directs the Creative Writing program at the University of Memphis, and gave a good, heartfelt presentation to a packed room. Interestingly, the room was packed with mostly women, which is highly unusual for nuclear-themed talks, in my experience.

The book is part memoir, part investigative account. Iversen’s family moved to Arvada, Colorado, in the late-1950s. Arvada, a small town north of Denver, was next to Rocky Flats, a plutonium fabrication facility owned by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and operated initially by Dow Chemical.

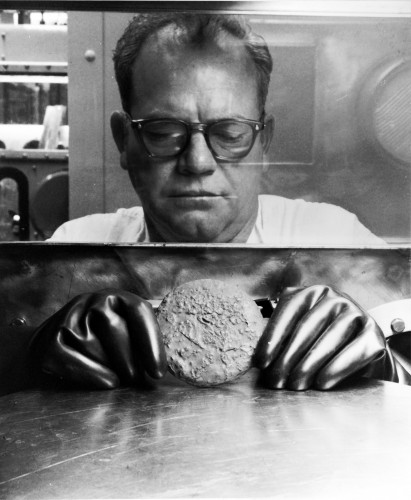

Hanford would breed the plutonium in their mammoth nuclear reactors, and the metal would be shipped to Rocky Flats, where workers would shape it into forms useful inside nuclear weapons — the “pits.” The pits would then be shipped to the Pantex Plant in Texas for final assembly into bombs.

In theory, all of this would be well-contained within glove boxes and filters and sensibly designed waste systems. In practice, plutonium is a messy substance, and for a variety of reasons, a lot of corners were cut. The result is that map up above — a fairly large plume of plutonium was deposited in the soil around the plant and the surrounding communities.

From Iversen’s presentation, it sounded like a pretty interesting read. It’s historical, it’s journalistic, and yet it’s read through the lens of the personal. This sort of thing is necessary — we need to keep in mind, when talking about grand strategy and big motivations, that there are all sorts of regular people caught up in this as well. That most of the world is not comprised of heads of state, or even heads of agencies.

The residents of the towns around Rocky Flats were ill served by nuclear secrecy. They weren’t told, for example, that a fire in 1957 spread a wide plume of radioactivity across the area. Or when it happened again in 1969. They weren’t given information on the sorts of diseases that are associated with coming into contact with heavy actinides. They were assured, again and again, that everything was under control.

And from Iversen’s account, most of them believed it. Why wouldn’t they? They had skin in that game — the livelihood of their town depended on it, and, as we’ve all seen again and again, human beings, for all of their famed skittishness, are quick to rationalize the big, unwieldly long-term risks that they live next door to. This is something that people in the field of risk communication have known for a long time: we learn to ignore risks that we live next to, especially when we have a personal incentive to do so. (In fact, many of those cut corners mentioned above were done by the employees themselves, because the profit incentive was on speed, not safety. This is unfortunately an all-too-common story with toxic industries.)

An “Infinity Room” at Rocky Flats — a room so contaminated by radiation that it was never to be occupied by unshielded humans again. From the DOE Digital Archive.

To give you an idea of how not under control things were, though, Iversen tells a gripping account of when the FBI raided Rocky Flats in 1989. Alerted by whistleblowers for egregious safety violations inside the plant, the FBI eventually concluded that the only way to find out what was being done inside Rocky Flats was to bust on inside. But you can’t just walk into a plutonium fabrication facility, even if you’re the FBI. So they came up with what was really an ingenious plan. The FBI told the Department of Energy officials at Rocky Flats that they had to brief all of them on a potential eco-terrorist threat — they said that Earth First was planning to attack the plant. Once the FBI had all of the senior management rounded up in a room for the briefing, they served them with search warrants, and along with the EPA, they invaded the facility and occupied it.

The DOE and the contractor (by then Rockwell) got off the hook pretty much scott free, despite plenty of evidence that they had in fact been complicit in plenty of environmental crimes — which are, as well, crimes against the community at large. Such is how things go, sometimes, when you’re talking about plants that do secret things for the nuclear weapons industry.

I’m looking forward to reading Iversen’s full book. Because I work primarily with records of the state, I always risk seeing like a state — or at least seeing history like one. Stories of the personal effects, ironically, can help one keep some distance from that standpoint. This isn’t to say that the personal, individual perspective is everything — the “big picture” still undoubtedly matters — but I think a serious historian excludes it at their peril.

One little announcement: In today’s issue of Science, I have a review published of Michael Gordin’s The Pseudoscience Wars: Immanuel Velikovksy and the Birth of the Modern Fringe (University of Chicago Press, 2012). I’ve reviewed a number of Michael’s books over the years, but I think this one is his best-written one yet, and I really enjoyed it a lot. It’s not very nuclear, but it does have an important Cold War theme. Check it out.

- A correspondent also notes that this heating is from alpha emission, which also tends to break the Pu-238 into small particles — meaning they can contaminate a volume rather quickly. Charming. [↩]

Hey Alex – Not to draw away from Ms. Iverson’s book, but your post reminded me of Len Ackland’s “Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West,” for the science geek in you.

Like Kevin said…

this is the science best blog of 2010-2012

how can i contribute/reward/say thanks?. is there a kindle book of yours I can buy?

um, best science blog… 🙂

There is a review on the amazon site that addresses a few technical points in the book, I wonder if after you’ve read the book you could comment on the accuracy as well?

http://www.amazon.com/review/R3Q71ICIAV2XAP/ref=cm_cr_pr_perm?ie=UTF8&ASIN=030795563X&linkCode=&nodeID=&tag=

I could, but I might note, a thousand tiny errors may not get away from the bigger point. I’m not against taking care of errors, of course — they should be fact-checked. Some of them seem to come from ambiguous writing (I’m not sure the author really believes that the bomb dropped on Nagasaki was a hydrogen bomb — I read the paragraph as trying to use Nagasaki as a baseline point of reference for explaining plutonium, but then mixing in a discussion of how plutonium “triggers” were used in the Cold War), some of them seem like incidental (and avoidable) errors that don’t detract much from what the author is trying to do (e.g. confusing Hesperium and Plutonium, which is avoidable and incorrect, but doesn’t really change things much).

But I find the final alleged “error” to probably be the most important to the heart of the matter, and probably not a valid criticism:

Actually, there are lots and lots of reasons why people might make decisions that inadvertently jeopardize themselves and their families. Cutting corners is common in every under-regulated industry. Those who live next to risks ignore them. And the Cold War necessities don’t really seem to justify shoddy working conditions and lack of oversight. Slipping that in there with the “small” factual errors is perhaps the most revealing of the mindset that I’m trying to address here — the one that comes out of thinking that the really important truths here are getting the numbers of the buildings right, as opposed to understanding the big picture.

[…] to live with it, in a sense. There’s no point in pretending I don’t find this stuff fascinating, even if it is macabre. I can’t hide it; the answer is not to pretend to be disinterested, […]

[…] biographical account of Rocky Flats was discussed by me in part here. […]

Have you seen this petition in regards to building a toll road on the Rocky Flats Area AKA Rocky Flats Wildlife Refuge?

For those interested, the Rocky Flats plant is located at 39.89039,-105.20377. If you use Google Earth, you can use the rollback mechanism to go back to 9/13/2002 (when it was still in production) and move forward one step at a time to watch it melt away.

Regarding books, there is also An Insider’s View of Rocky Flats: Urban Myths Debunked by Farrel Hobbs.