Last week I gave a talk at a conference on “Nuclear Legacies” at Princeton University on Kyoto and Kokura, the two most prominent “spared” targets for the atomic bomb in 1945. The paper grew out of ideas I first put to writing in two blog posts (“The Kyoto misconception” and “The luck of Kokura“), and argues, in essence, that looking closely at these targeted-but-not-bombed cities gives us new insights into both the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Importantly, they both end up highlighting different aspects of what Truman did and did not know about the atomic bombings — my thesis is that on several important issues (notably the nature of the targets and the timing of the bombs), Truman was confused.

Niigata city today. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The basic stories of how Kyoto and Kokura avoided the bomb are known (though, as I argue, the devil is in the details). Kyoto was the military’s first choice for an atomic bombing target, but vetoed by the Secretary of War and eventually Truman himself. Kokura was the primary target for the second atomic bombing mission, but the target was obscured by clouds, smoke, and/or haze, and so the secondary target, Nagasaki, was bombed instead.

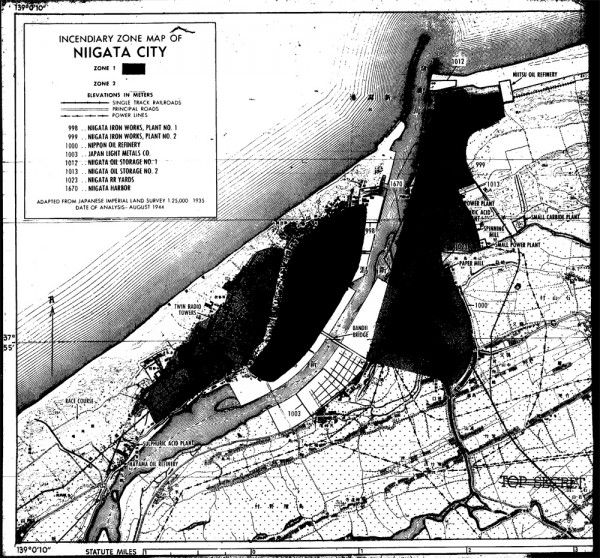

There was another target on the atomic bombing list, however, one the literature almost completely ignores: Niigata.

Niigata had been on the list of possible targets for quite some time. It was a port city in north-west Honshu. The notes of the second Target Committee meeting described it thusly:

Niigata – This is a port of embarkation on the N.W. coast of Honshu. Its importance is increasing as other ports are damaged. Machine tool industries are located there and it is a potential center for industrial despersion [sic]. It has oil refineries and storage. (Classified as a B Target)1

That’s not a very enthusiastic write-up, and it’s not surprising that it was the lowest priority recommended target (and had the lowest classification rating by the US Army Air Forces). It was the target about which they had the least to say.

The relative merits of Kokura and Niigata in the notes of the second meeting of the Target Committee, May 1945. Kokura was an exciting target; Niigata, not so much.

Groves got a report on In early July 1945, Groves received “New Dope on Cities” that included a fact-sheet on Niigata. It identified several useful industries, but it is much less exciting than the write-ups for Kyoto, Hiroshima, or Kokura. Niigata was noted as:

Principally important for aluminum, machine tools and railroad equipment. Also located here are small oil refineries, several chemical plants and woodworking plants. The harbor has been much improved and has extensive storage and trans-shipment facilities.2

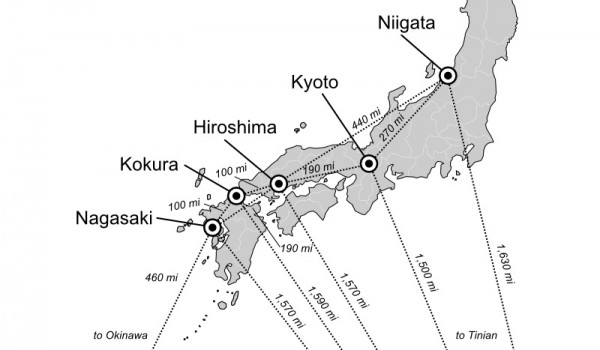

It’s hard not to yawn at this. By contrast, Kyoto was written about as a major city of military and industrial importance, and Kokura was “one of the largest arsenals in Japan.” So they weren’t that enthusiastic about Niigata. But still, it was on the short-list of targets, and it was on the list of targets “reserved” from conventional bombing (unlike Nagasaki).3 Why didn’t it end up on any of the missions, even as a backup target? (The first bomb’s targets were, Hiroshima, Kokura, and Nagasaki, in that order of priority; the second bomb’s targets were Kokura and Nagasaki, in that order.)

The five atomic targets of 1945, with distances between each other and relevant bases indicated. All distance measurements are great-circle routes, approximated with Google Earth.

The easiest and most plausible answer as why it wasn’t on those orders is a geographical one. Niigata was some 440 miles away from Hiroshima, the other closest target on the final list. By contrast, the other three main targets (Hiroshima, Kokura, Nagasaki) were all around 100-200 miles from one another. When you’re flying a B-29 carrying a five-ton bomb, every mile starts to matter in terms of fuel, especially when the trip from Tinian is going to be another 1,500 miles, and ditto the trip back (though Okinawa was only about 470 miles from Nagasaki). Truman’s memoirs say that Niigata “had been ruled out as too distant” for the first two raids. While I am inherently suspicious of postwar memoirs (they tend to smooth out and rationalize what was at the time a rather chaotic series of events and choices), and especially Truman’s, this sounds plausible.4

So we don’t talk about Niigata. Would it have been bombed next, if future atomic bombing runs were going to happen? Truman claimed later that this was definitely the case, but we really don’t know whether they would have continued to use them on cities, or whether they would have tried to use them “tactically.” Though there were a number of ideas floating around for what a “third shot” might look like, none of them ever got to a stage of planning that in retrospect looks official. So we just don’t know. I suspect that if they were going to bomb another city, the next one would be Kokura. They had that mission well-planned out (it was, after all, the initial choice for the Nagasaki bombing), and its target profile would make “good use” of the specific types of forces the atomic bomb was capable of (very heavy pressures near ground zero, lighter pressures around — great for a city with a military/industrial arsenal at the center of it and surrounded by workers’ housing), and for a President who was beginning to tire of the loss of civilian life, bombing a military arsenal would look a lot more like what he imagined the atomic bomb was being used for than the horror visions of dead women and children that he was reading about in the newspapers.

There were those at the time (notably General Carl Spaatz) who argued for using the next bomb on Tokyo, but I doubt they would have done that. Killing the Emperor would have severely complicated the surrender process (because it would have set off a crisis of political succession) and the city was too bombed-out for the bomb to look very impressive. My basis for thinking this reasoning would matter to them is based on target discussions prior to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, though; it is pretty hard to say how they thought about their original target criteria after the bombs were used.

(One of my messages in my talk at Princeton, incidentally, is that scholars of this subject need to be very explicit about where they are making interpretive leaps. We have a few very useful “data points” in terms of documents, recollections, interviews. We are all trying to weave a plausible narrative through those data points. Many writers on this subject smooth over these jumps with “probably,” “it is likely,” “it seems plausible,” and other elisions. I get why they do it — there is an impulse to make things look neat and tidy, and it can wreck a story to constantly point out where you are making a huge assumption. But it often makes this literature look much more “concrete” than it actually is, and the more I dig into the documents and footnotes, the more I find that there are very important and conspicuous gaps in our knowledge of these events, and there are multiple, radically-different narratives consistent with the “data.” So I think we ought to foreground these, both for our readers, and ourselves — the gaps are not things to be embarrassed about, but challenges to be embraced.)

But to return to Niigata: so why was it on the list in the first place, if it wasn’t close to any of the other targets? Ah, but it wasn’t very far from Kyoto, Tokyo, and Yokohama — a few of the other potential targets discussed around the time Niigata was added to the list. (Niigata is 270 miles from Kyoto, 170 miles from Tokyo and Yokohama.) So in that sense, Niigata tells us something else about the removal of Kyoto: if Kyoto had been on the target list, would Niigata have been one of the backup targets, to be used if the weather was better there than Kyoto or Hiroshima? This is just speculation, but that seems plausible to me. If that’s the case, then taking Kyoto off the list spared two cities, not just one. And Niigata’s inclusion possibly a relic of an earlier targeting debate, one made less relevant by August of 1945.

Of course, in this case, “sparing” is a zero-sum game: one city’s reprieve was another’s doom. Just ask Nagasaki, a city that no doubt would have preferred circumstances that would have given it Niigata’s relative lack of attention from historians.

- J.A. Derry and N.F. Ramsey to L.R. Groves, “Summary of Target Committee Meetings on 10 and 11 May 1945,” in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 1, Target 6, Folder 5D, “Selection of Targets.” [↩]

- “New Dope on Cities,” (14 June 1945, but with some files dated later), in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 3, Target 8, Folder 25, “Documents Removed From Groves’ Locked Box.” [↩]

- “Reserved Areas” (27 June 1945), in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 3, Target 8, Folder 25, “Documents Removed From Groves’ Locked Box.” [↩]

- Harry S. Truman, Memoirs: Volume 1, Year of Decisions (New York: Signet Books, 1965), 470. [↩]

Good job, Alex.

I have read and found your article informative. Thank you, but where I also think the reason the city was spared was because there were many P.O.W.s in Niigata who were working the mines. Very little is written up about that, so it’s worth looking into.

There were POW camps in most of the selected cities (Hiroshima was an exception as far as they know; is one of the reasons it was so appealing as a target); I suspect it was purely geography that spared Niigata (it did not help Nagasaki even though they did have knowledge of POW camps there as well).

It looks as if a B29 from Tinian to Niigata would have to overfly land to a greater extent than with any of the other target cities. Could that have been a factor? While Japan didn’t have much antiaircraft capability by August 1945 I would presume that it wasn’t entirely gone.

Yeah, I thought about that too. I doubt it would have been a straight as-the-crow-flies attack, given that they would not have wanted to pass over Tokyo (which was still defended by a lot of anti-air fire). Avoiding anti-aircraft would have required making the distance even longer. The Japanese were concentrating their limited anti-air on major targets but it was not completely nonexistent.

Your parenthetical paragraph is a lesson in itself, to those wishing to do history of any kind:

…there are very important and conspicuous gaps in our knowledge of these events, and there are multiple, radically-different narratives consistent with the “data.” So I think we ought to foreground these, both for our readers, and ourselves —

Gave me food for thought.

The most astonishing and depressing fact about this information about the discussions of targets for the first use of atomic weapons is the complete disregard of the obligation, by the conventional laws of war, not to cause civilian casualties. Indeed, it became clear to me by the quotations of Truman’s contemporary remarks, that he was completely callous about killing and injuring “Japs,” who he seems to have regarded as less than real human beings. But contemporary commentators, also, appear not to have thought about the fact that deliberately targeting populous cities where the feasible military targets were surrounded by great numbers of innocent civilians was a war crime! The only previous commentator who had any similar concern noted the possible endangerment of American POWs if some locations had been targeted. As if only our guys had lives one should not hesitate to take.

A bit off topic here. But I remember that Emilio Segrè (in the 80s, Rome, La Sapienza Univ., he teached physics) told me the the very first target was Berlin. When it appeared that was too late to A-bomb Berlin (and Germany) a huge discouragement spread among physicists there.

It’s possible that many of the scientists thought this was the case, but there is no record of any high-level discussions about Berlin. Doesn’t mean they didn’t happen — but I doubt they plotted it out in a serious way.