The Smyth Report is one of the more improbable things to come out of World War II. It is one thing to imagine the United States managing to take nuclear fission, a brand-new scientific discovery announced in 1939, and to have developed two fully-realized industrial-methods of enriching uranium, three industrial-sized nuclear reactors (plus several experimental ones), and three nuclear weapons by the summer of 1945. That improbable enough already, especially since their full-scale work on the project did not begin until late 1942. What really takes it into strange territory is to then imagine that, right after using said superweapon, they published a book explaining how it was made. I can think of no other parallel situation in history, before or since.

The original press release about the Smyth Report, issued only a few days after the Nagasaki bombing. Truman himself personally made the final decision over whether the report should be issued. Source: Manhattan District History Book 1, Volume 4, Chapter 8.

I have written on the Smyth Report before, talking about the paradoxical mix of motivations that led to its creation: the civilian scientists wanted the American people to have the facts so they could be good citizens in a democracy, while the military wanted something that set the limits of what was allowable speech. Groves and his representatives (namely Henry Smyth and Richard Tolman) devised the first declassification criteria for nuclear weapons in deciding what to allow into the report and what not to. Groves was concerned about secret details, but not the big picture (e.g., which methods of producing fissile material had worked and how they roughly worked), which he thought would be too easy to learn from newspaper accounts. There were those even at the time who criticized this approach, since it is the big picture that might provide the roadmap to a bomb, and the details would emerge to anyone who started on that journey.

The Soviets, in any case, quickly translated the Smyth Report into Russian. The Russian Smyth Report is a very faithful and careful translation. The American physicist Arnold Kramish reviewed it in 1948, and noticed that the Soviets managed to produce a document that showed they were paying very close attention to the original — specifically, that they had multiple editions of the Smyth Report, and noticed differences. The first edition of the Smyth Report was a lithoprint created by the Army, and only around 1,000 copies were printed and released a few days after the bombing of Nagasaki. A spiffed-up edition was published by Princeton University Press, under the title Atomic Energy for Military Purposes, in September 1945. Most of the differences between the two editions are cosmetic, like using full names for scientists instead of initials. In a few places, there are minor additions to the Princeton University Press edition.1

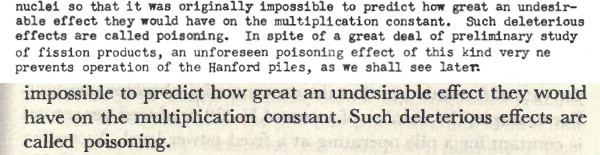

Now you see it, now you don’t… comparing the sections on “pile poisoning” in the original lithograph edition of the Smyth Report (top) and the later version published by Princeton University Press (bottom) reveals the omission of a crucial sentence that indicates that this problem was not merely a theoretical one. (Note: the top image is a composite of a paragraph that runs across two pages, which is why the font weight changes in a subtle way.)

But there is at least one instance of the Manhattan Project personnel deciding to remove something from the later edition. The major one noted by Kramish is what was called the “poisoning” problem. In the lithoprint version of the Smyth Report that was released in August 1945, there was a paragraph about a problem they had in the Hanford piles:

Even at the high power level used in the Hanford piles, only a few grams of U-238 and of U-235 are used up per day per million grams of uranium present. Nevertheless the effects of these changes are very important. As the U-235 is becoming depleted, the concentration of plutonium is increasing. Fortunately, plutonium itself is fissionable by thermal neutrons and so tends to counterbalance the decrease of U-235 as far as maintaining the chain reaction is concerned. However, other fission products are being produced also. These consist typically of unstable and relatively unfamiliar nuclei so that it was originally impossible to predict how great an undesirable effect they would have on the multiplication constant. Such deleterious effects are called poisoning. In spite of a great deal of preliminary study of fission products, an unforeseen poisoning effect of this kind very nearly prevents operation of the Hanford piles, as we shall see later.

Reactor “poisoning” refers to the fact that certain fission products created by the fission process can make further fissioning difficult. There are several problematic isotopes for this. There are ways to compensate for the problem (namely, run the reactor at higher power), but it caused some anxiety in the early trials of the B-Reactor. The question of whether to include a reference to this was considered a “borderline” secret by Groves when Smyth was writing the report, but it got added in. Apparently someone had second thoughts after it was released, and so the sentence I’ve put in italics in the quote above was deleted from the Princeton University Press edition. The Russian Smyth Report claimed to be — and shows evidence of — having used the Princeton University Press edition as its main reference. However, that particular sentence about poisoning shows up in the Russian edition, word-for-word.2

“Atomic Energy for Military Purposes,” first edition of the Soviet Smyth Report translation made by G.M. Ivanov and published by the State Railway Transportation Publishing House, 1946. Source.

Kramish concluded:

I think it is significant in that here we have evidence that at least one Soviet technical man has screened the Smyth Report in great detail and it is very unlikely that some of the references which we have hoped “maybe they won’t notice” have not been noticed. With particular regard to the statement that fission product poisoning very nearly prevents the operation of the Hanford piles, we must realize that that information most certainly has been compromised.3

This serves as a wonderful example of a very common principle in secrecy: if someone notices you trying to keep a secret, you will serve to draw more attention to what you are trying to hide.

But who read the Russian Smyth Report? I mean, other than the people actually participating in the Soviet atomic bomb project. Apparently it was published and available quite widely in the Soviet Union, which is an interesting fact in and of itself. One imagines that the American works that were chosen to be translated into Russian and mass-published must have been pretty selective during the Stalin years; a report about the United State’s atomic energy triumphs made the grade, for whatever reason.

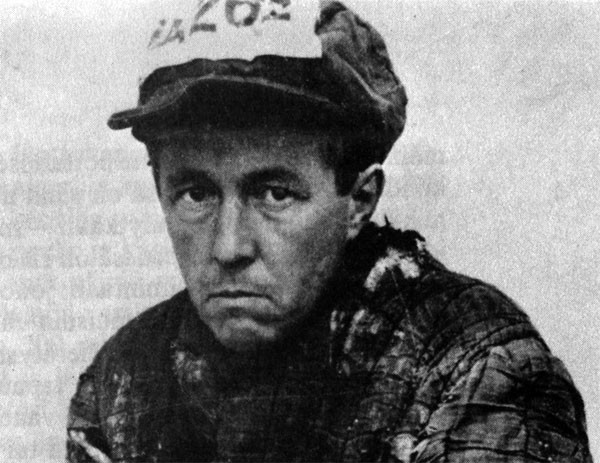

Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag mugshot from 1953. Source: Gulag Archipelago, scanned version from Wikimedia.org.

Which brings me to the event that got me thinking about the Russian Smyth Report again. For the past few years, on and off, I’ve been making my way through the unabridged edition of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. It’s a long work, and historians take it with a grain of salt (it is not a work of academic history to say the least), but I find it fascinating, at times darkly humorous, at times shocking. Some of the chapters are skimmable (Solzhenitsyn has axes to grind that mean little to me at this point — e.g. against specific Soviet-era prosecutors). But occasionally there are just some really unexpected and surprising little anecdotes. And one of those involves the Smyth Report.

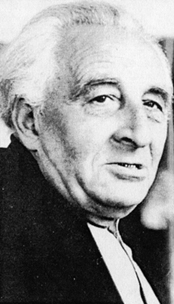

Timofeev-Ressovsky. Source.

At one point, Solzhenitsyn talks about his time in the Butyrskaya prison, a “hub” for transferring Gulag prisoners between different camps, albeit one that it was (in Solzhenitsyn’s account) easy to get “stuck” in while they were figuring out what to do with you (and perhaps forgetting about you). Shortly after he arrived, he was approached by “a man who was middle-aged, broad-shouldered yet very skinny, with a slightly aquiline nose.” The man, another prisoner, introduced himself: “[I am] Professor Timofeyev-Ressovsky, President of the Scientific and Technical Society of Cell 75. Our society assembles every day after the morning bread ration, next to the left window. Perhaps you could deliver a scientific report to us? What precisely might it be?” He was none other than the eminent biologist and geneticist Nikolai Timofeev-Ressovsky, a victim of Lysenkoism who had taken up a post in Germany before the rise of the Nazis, been re-captured in the Soviet invasion, and thrown into prison. Timofeev-Ressovsky, though not a name that rolls of the tongue today, was one of the most famous Russian biologists of his time, and one of the world experts on the biological effects of ionizing radiation. And, true to form, he had organized a science seminar in his cell while in Butyrskaya.

Solzhenitsyn continued:

Caught unaware, I stood before him in my long bedraggled overcoat and winter cap (those arrested in winter are foredoomed to go about in winter clothing during the summer too). My fingers had not yet straightened out that morning and were all scratched. What kind of scientific report could I give? And right then I remembered that in camp I had recently held in my hands for two nights the Smyth Report, the official report of the United States Defense Department on the first atom bomb, which had been brought in from outside. The book had been published that spring. Had anyone in the cell seen it? It was a useless question. Of course no one had. And thus it was that fate played its joke, compelling me, in spite of everything, to stray into nuclear physics, the same field in which I had registered on the Gulag card.4

After the rations were issued, the Scientific and Technical Society of Cell 75, consisting of ten or so people, assembled at the left window and I made my report and was accepted into the society. I had forgotten some things, and I could not fully comprehend others, and Timofeyev-Ressovsky, even though he had been in prison for a year and knew nothing of the atom bomb, was able on occasion to fill in the missing parts of my account. An empty cigarette pack was my blackboard, and I held an illegal fragment of pencil lead. Nikolai Vladimirovich took them away from me and sketched and interrupted, commenting with as much self-assurance as if he had been a physicist from the Los Alamos group itself.5

What are the odds of all of this having happened? The Smyth Report itself was pretty improbable. The Soviets deciding to publish it themselves strikes me as unpredictable. That Solzhenitsyn would run across it in a camp seems entirely fortuitous. And finally, that Solzhenitsyn would be the one who would end up explaining it to Timofeyev-Ressovsky, an expert on the radiation effects, seems like a coincidence that a writer would abhor — it’s just too unlikely.

And yet, sometimes history lines up in peculiar ways, does it not? I am sure it never occurred to Smyth, or to Groves, that the report would end up being much-sought-after Gulag reading.

- On the publication history of the Smyth Report, see both H.D. Smyth, “The ‘Smyth Report’,” and Datus C. Smith, Jr., “The Publishing History of the ‘Smyth Report,'” both in Princeton University Library Chronicle 37, no. 3 (Spring 1976), 173-190, 191-203, respectively. For a copy of the lithograph version of the report, see the Manhattan District History, Book 1, Vol. 4, Chapter 8, Part 2. A scanned copy of the Princeton University Press edition is available on Archive.org. [↩]

- “Несмотря на большое количество предварительных исследований продуктов деления, непредвиденный отравляющий эффект такого рода едва не заставил приостановить работы в Хэнфорде, с чем мы встретимся позднее.” A transcribed copy of the Russian Smyth Report can be found online here.) Cf. Henry D. Smyth, Atomic Energy for Military Purposes (Princeton University Press, 1945), 135, and paragraph 8.15 in the lithograph edition. [↩]

- Arnold Kramish to H.A. Fidler, “Russian Smyth Report,” (18 September 1948), in Richard C. Tolman Papers, Caltech Institute Archives, Pasadena, California, Box 5, Folder 4. [↩]

- Solzhenitsyn recorded his “occupation” as “nuclear physicist” on his Gulag registration card on a whim, despite knowing nothing about nuclear physics. Elsewhere in the book he refers to nuclear physics as the kind of intellectual “hobby” that one who was not engaged with the world might think about, not realizing the horrors that lurked behind the curtain of Soviet society. The presence of nuclear themes in Solzhenitsyn’s work is probably fodder for a Slavic studies article. [↩]

- Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, I-II, Thomas P. Whitney, trans. (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), 598-599. [↩]

You’ve reminded me that Gordin’s “Red Cloud at Dawn” has a pretty interesting explainer on the Soviet reaction to the Smyth Report that made me not discount Solzhenitsyn’s account. From p. 100:

Nice work, Alex. You piqued my interest about the deletion, so I compared my multiple copies of the Smyth Report. The British edition, published in 1945 by His Majesty’s Stationery Office, included the deleted sentence. So did the 1947 reprinting of the U.S. Government Printing Office edition. It seems that the left hand of the censor didn’t know what the right hand was doing.