A quick dispatch from the road: I have been traveling this week, first to Washington, DC, and now in New Mexico, where I am posting this from. Highlights in Washington included giving a talk on nuclear history (what it was, why it was important) to a crowd of mostly-millennial, aspiring policy wonks at the State Department’s 2015 “Generation Prague” conference. A few hours after that was completed, an article I wrote on the Trinity test went online on the New Yorker’s “Elements” science blog: “The First Light of Trinity.”

Being able to write something for them has been a real capstone to the summer for me. It was a lot of work, in terms of the writing, the editing, and the fact-checking processes. But it is really a nice piece for it. I am incredibly grateful to the editor and fact-checker who worked with me on it, and gave me the opportunity to publish it. Something to check off the bucket list.

On the plane to New Mexico, I thought over what the 70th anniversary of Trinity really meant to me. I keep coming back to the post-detonation quote of Kenneth Bainbridge, the director of the Trinity project: “Now we are all sons of bitches.” It is often put in contrast with J. Robert Oppenheimer’s more grandiose, more cryptic, “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” Oppenheimer clearly didn’t say this at the time of test explosion, and its meaning is often misunderstood. But Bainbridge’s quote is somewhat cryptic and easy to misunderstand as well.

The Los Alamos badge photograph of Kenneth Bainbridge, director of the Trinity project. From a photo essay I wrote for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists two years ago.

Bainbridge’s quote first got a lot of exposure when it was published as part of Lansing Lamont’s 1965 book, Day of Trinity, timed for the 20th anniversary of Trinity. Lamont interviewed many of the project participants who were still alive. The book contains many errors, which many of them lamented. (The best single book on Trinity, as an aside, is Ferenc Szasz’s 1984, The Day the Sun Rose Twice, by a considerable margin.) A consequence of these errors is that a lot of the scientists interviewed wrote letters to each other to complain about them, which means they also clarified some quotes of theirs in the book. Bainbridge in particular has a number of letters related to mixed up quotes, mixed up content, and mixed up facts from the Lamont book in his personal papers kept at the Harvard University Archives, which I looked at several years back.

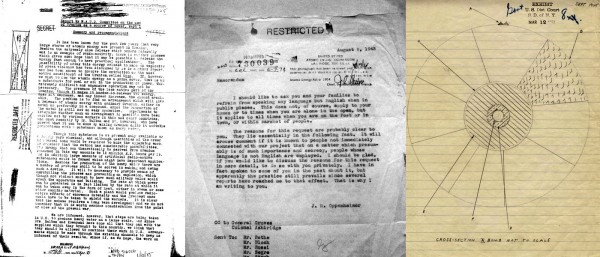

One of the people Bainbridge wrote to was Oppenheimer. He said he wanted to explain his “Now we are all sons of bitches” quote, to make sure Oppenheimer understood he was not trying to be offensive:

The reasons for my statement were complex but two predominated. I was saying in effect that we had all worked hard to complete a weapon which would shorten the war but posterity would not consider that phase of it and would judge the effort as the creation of an unspeakable weapon by unfeeling people. I was also saying that the weapon was terrible and those who contributed to its development must share in any condemnation of it. Those who object to the language certainly could not have lived at Trinity for any length of time.

Oppenheimer wrote back, in a letter dated 1966, just a year before his death, when he was pretty sick and in a lot of pain. It said:

When Lamont’s book on Trinity came, I first showed it to Kitty; and a moment later I heard her in the most unseemly laughter. She had found the preposterous piece about the ‘obscure lines from a sonnet of Baudelaire.’ But despite this, and all else that was wrong with it, the book was worth something to me because it recalled your words. I had not remembered them, but I did and do recall them. We do not have to explain them to anyone.1

I like Bainbridge’s explanation, because it doubles back on itself: people will think we were unfeeling and terrible for making this weapon, which makes it sound like the people are not understanding, but, actually, yes, the weapon was terrible. I think you can get away with that kind of blanket condemnation if you’re one of the people instrumental in its creation.

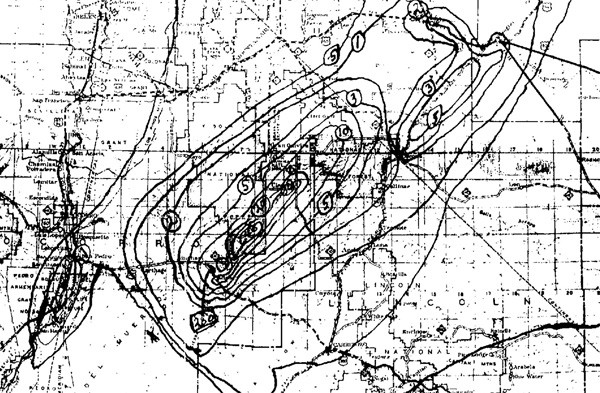

The original map of fallout from the Trinity test. There are several more “hot spots” to the South and West than are in the later more simplified drawings of it. Click the image to see the entire map at full resolution.

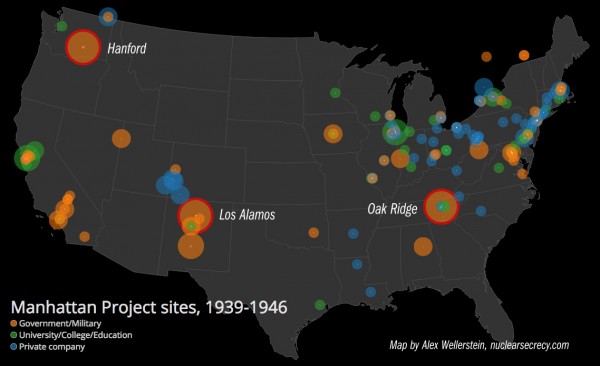

I have been thinking about how broadly one might want to expand the “we” in his quote. Just those at the Trinity test? Those scientists who made the bombs possible? All of the half-million involved in making the bomb, whether they knew their role or not? The United States government and population, from Roosevelt on down? The Germans, the fear of whom inspired its initial creation? The world as a whole in the 1940s? Humanity as a whole, ever?

Are we all sons of bitches, because we, as a species of sentient, intelligent, brilliant creatures have created such terrible means of doing violence to ourselves, to the extremes of potential extinction?

This is probably not what Bainbridge meant, but it is an interesting road to go down. It recalls the recent discussions about whether we live in a new era of time, the Anthropocene, and whether the Trinity test should be seen as the marker of its beginning, as some have argued.

The late stages of the Trinity cloud as viewed from many miles distant, as it becomes a shifting, twisting column of radioactive dust. Obtained from Los Alamos National Laboratory.

I can see why a lot of people object to using the Trinity test as that marker: it was hardly the dawn of the human species’ ability to manipulate the planet on a large scale, and it does seem to put an awful lot of emphasis on nuclear weapons as the point at which everything changed. This is hard to defend from a historical or even scientific point of view, I think. And there are some, of course, who think that this is too glorifying of the Trinity test itself. It is also a little arbitrary feeling. I see where all of these objections are coming from.

But from a literary, poetic point of view, I think it is a not entirely invalid interpretation of Bainbridge’s quote to say, well, we are all sons of bitches, where we are all people, and by sons of bitches, we mean that we’ve crossed some sort of line where annihilation starts to look like a realistic possibility. Where we wonder if the answer to the Fermi paradox is that all sufficiently advanced civilizations kill themselves within a few centuries of developing nuclear weapons.2 In other words, perhaps the Trinity test marks not an actual, technical line crossed, but rather the crossing of a line of perception, of an that causes a large number of human beings, both expert and not, to suddenly see the possibility of total annihilation rushing up at them.

- Regarding Baudelaire, supposedly, according to Lamont, this was going to be the code that Oppenheimer used to tell Kitty that the test was a success: “If the test succeeded, he would send her a brief message, an obscure line from a sonnet by Baudelaire: ‘You can change the sheets.'” [↩]

- The Fermi paradox, which asks why we do not see evidence of other intelligence life in the universe (despite its age and the vastness), was conceived at Los Alamos while Fermi and others were working on even that even more terrible weapon, the hydrogen bomb. [↩]