This is the second and final part (Part II) of my story about the lost Oppenheimer transcripts. Click here for Part I, which concerns the origin of the transcripts, the unintuitive aspects of their redaction, and the unorthodox archival practice that led me to find their location in 2009.

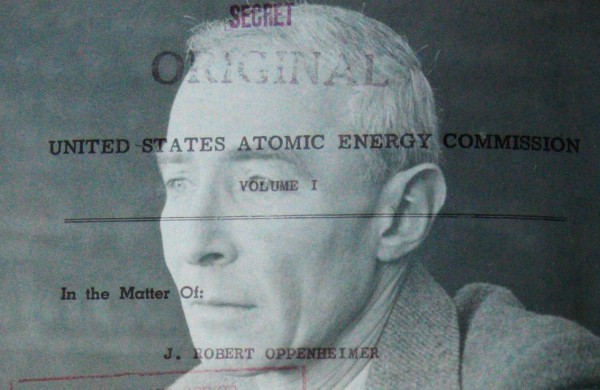

The Oppenheimer security hearing transcript is not exactly beach reading. Aside from its length (the redacted version alone is some 690,000 words, which makes it considerably longer than War and Peace), it is also a jumble of witnesses, testimonies, and distinct topics. It is also somewhat of a bore, as there is incredible repetition, and unless you know the context of the time very well, the specific arguments that are focused on can seem arbitrary, pedantic, and confusing, even without the additional burden of some of the content having been deleted by the censor.

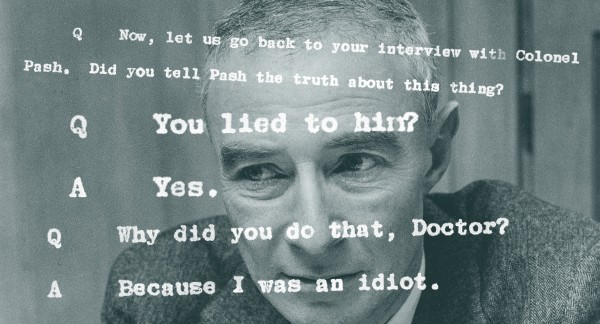

The most damning problem for Oppenheimer at his 1954 hearing involved his conduct during the so-called “Chevalier incident,” in which a fellow-traveler colleague of his at Berkeley, Haakon Chevalier, approached Oppenheimer at a party in late 1942 or early 1943 at the behest of another scientist (a physicist named George Eltenton) who wanted to see if Oppenheimer was interested in passing on classified information to the Soviet Union. Oppenheimer, in his recollection, told Chevalier in no uncertain terms that this was a bad idea. Later, Oppenheimer went to a member of the Manhattan Project security team and told him about the incident, calling attention to Eltenton as a security risk, but also trying to not to make too big of a deal of the entire matter. Confronted with the idea of Soviet spying on the atomic bomb project, the security men of course did not take it so lightly, and pressed Oppenheimer for more details, such as the name of the intermediary, Chevalier, which Oppenheimer did not want to give since he claimed Chevalier had nothing truly to do with Soviet spying. Over the course of several years, the security agents re-interviewed Oppenheimer, trying to clarify exactly what had happened. Oppenheimer gave contradictory answers, seemingly to shield his friends from official scrutiny and its consequences. At his hearing, when asked whether he had lied to security officials, Oppenheimer admitted that he had. When asked why, Oppenheimer gave what was become the most damning testimony at a hearing about his character: “Because I was an idiot.” Not a good answer to have to give under any context, much less McCarthyism, much less when you are known to be brilliant.

I mention this only to highlight the difference between what is in the published transcript and what is not. The newly unredacted information does not touch on the Chevalier incident much at all. That is, it does not shed any new light on the central question of relevance towards Oppenheimer’s security clearance. What does it shed light on? We can lump its topics into roughly three categories.

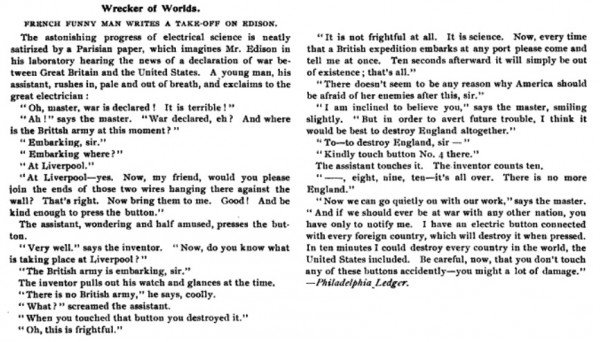

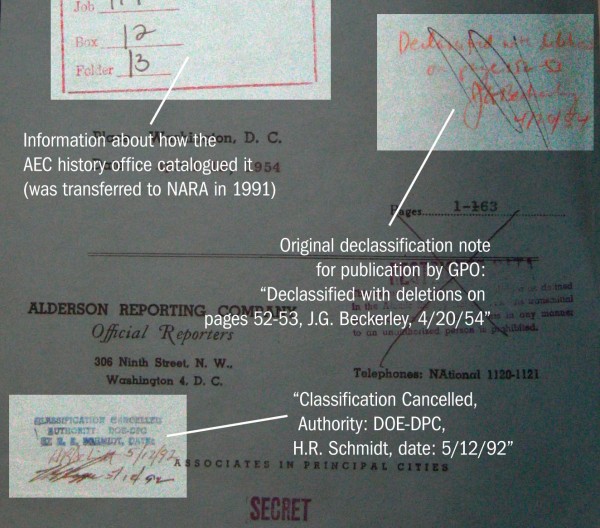

One of the censor’s trickier redactions, in which he removed a trouble word, and substituted a different word in its place. “Principle” was too close to a secret, but”idea” was acceptable. (JB = James Beckerley.)

The first category concerns the creation of the hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer had been on a committee that had opposed a “crash” program to build the H-bomb in 1949. This was at a time when it was unclear that such a weapon could be built at all. The then-favored design (later dubbed the “Classical Super”) had many problems with it, and didn’t seem like it was likely to work. It seemed to also require huge quantities of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium, the production of which could only be done in nuclear reactors at the expense of producing plutonium.For Oppenheimer and many others, there was a strong technical reason to not rush into an H-bomb program: it wasn’t clear that the bomb could be built, and preparing the materials for such a bomb would decrease the rate of producing regular fission bombs.

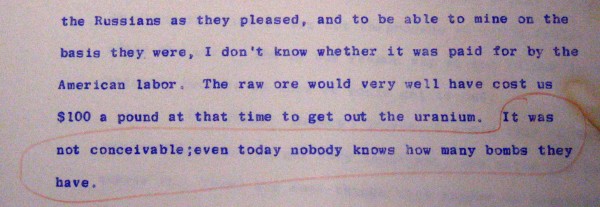

How much plutonium would be lost in pursuing the Super? This is an area the newly-reduced transcript does enlighten us. Gordon Dean, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1950 to 1953, explained that:

You don’t decide to manufacture something that has never been invented. Nothing had been invented. No one had any idea what the cost of this thing would be in terms of plutonium bombs. As the debate or discussions waged in the fall of 1949, we had so little information that it was very difficult to know whether this was the wise thing to do to go after a bomb that might cost us anywhere from 20 plutonium bombs up to 80 plutonium bombs, and then after 2 or 3 years effort find that ft didn’t work. That was the kind of problem. So there were some economics in this thing.

The underlined section was removed from the published transcript. This does contribute to the debate at the time — if researching the Super meant depriving the US stockpile of 20-80 fission bombs, that is indeed a high price. We might ask: Why was it redacted? Because the censor wanted to undercut Oppenheimer’s position? Probably not — if the censor had wanted to do that, he would have removed a lot more than just those numbers. More likely it is because you can work backwards from those numbers how much plutonium was in US nuclear weapons at that time, or, conversely, how much tritium they were talking about. Every atom of tritium you make is an atom of plutonium you don’t make — and plutonium atoms are 80X heavier than tritium atoms. So for every gram of tritium you produce, you are missing out on 80 grams of plutonium. If you know that the bombs at the time had around 6 kg of plutonium in them, then you can see that they are talking about the expense of making just 1.5 to 6 kg of tritium. Should this have been classified? It seems benign at the moment, but this was still a period of a “race” for thermonuclear weapons, and nearly everything about these weapons was, rightly or wrongly, classified.

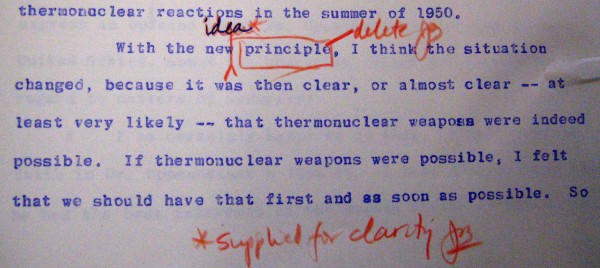

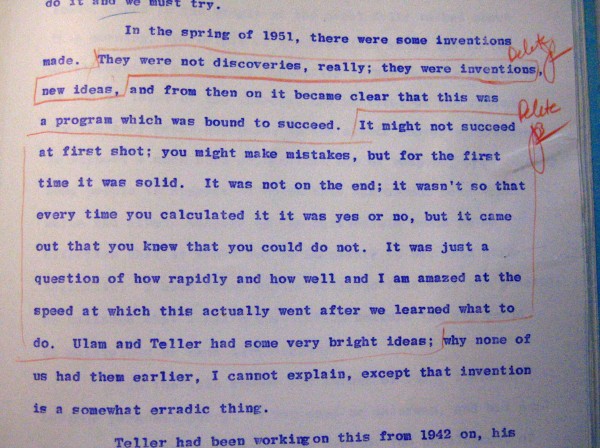

Redaction of a long section on the development of the Teller-Ulam design. Ulam’s name was almost totally (but not entirely) removed from the transcript, sometimes very deliberately and specifically. The orange pencil shows the mark of the censor, as does the “Delete, JB” on the right.

But the hydrogen bomb could be built. In the spring of 1951, physicists Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam hit upon a new way to build a hydrogen bomb. It was, from the point of view of the weapons physicists, a totally different approach. Whereas the “Classical Super” required using an atomic bomb to start a small amount of fusion reactions that would then propagate through a long tube of fusion fuel, the “Equilibrium Super,” as the so-called Teller-Ulam design was known at the time, involved using the radiation of an atomic bomb to compress a capsule of fusion fuel to very high densities before trying to ignite it. To a layman the distinction may seem minor, but the point is that many of the scientists involved with the work felt this was really quite a big conceptual leap, and that this had political consequences.

The differences between the redacted and un-redacted transcript shows a censor who tried, perhaps in vain, to dance around this topic. The censor clearly wanted to make sure the reader knew that the hydrogen bomb design developed in 1951 (the “Equilibrium Super”) was a very different thing than the one on the table in 1949 (the “Classical Super”), because this is a clear part of the argument in Oppenheimer’s favor. But the censor also evidently feared being too coy about what the differences between the 1949 and 1951 designs were, as such was the entire “secret” of the hydrogen bomb. For example, here is a section where Oppenheimer testified on this point, early on in the hearing:

In the spring of 1951, there were some inventions made. They were not discoveries, really; they were inventions, new ideas, and from then on it became clear that this was a program which was bound to succeed. It might not succeed at first shot; you might make mistakes, but for the first time it was solid. It was not on the end; it wasn’t so that every time you calculated it it was yes or not, but it came out that you knew that you could do not. It was just a question of how rapidly and how well and I am amazed at the speed at which this actually went after we learned what to do. Ulam and Teller had some very bright ideas; why none of us had them earlier, I cannot explain, except that invention is a somewhat erratic thing.

Again, what is underlined above was removed from the original. Read the sentences without them and they still have the same essential meaning: Oppenheimer is arguing that the 1951 design was very different than the 1949 one. Put them back in, and the meaning only deepens a little, adding a little more specifics and context, but does not change. One still understands Oppenheimer’s point, and much is left in to emphasize its import — Oppenheimer only opposed the H-bomb when it wasn’t clear that an H-bomb could be made.

Why remove such lines in the first place? A judgment call, perhaps, about not wanting to reveal that the “secret” H-bomb was not a new scientific fact, but a clever application of a new idea. The censor could have probably justified removing more under the security guidelines, but took pains to maintain coherency in the testimony. In one place, the physicist Hans Bethe referred to Teller and Ulam’s work as a new “principle,” and the censor re-worded this to “idea” instead. A subtle change, but certainly done in the name of security, to shift attention away from the nature of the H-bomb “secret.”

Early 1954 was a tricky time for hydrogen bomb classification. The US had detonated its first H-bomb in 1952, but not told anyone. In March 1954, a second hydrogen bomb was detonated as the “Bravo test.” Radioactive fallout rained down on inhabited atolls in the Marshall Islands, as well as a Japanese fishing boat, making the fact of it being a thermonuclear test undeniable. The Soviet Union had detonated a weapon that used fusion reactions in 1953, but did not appear to know about the Teller-Ulam design. As a result, US classification policy on the H-bomb was extremely conservative and sometimes contradictory; that the US had tested an H-bomb was admitted, but whether it was ready to drop any of them was not.

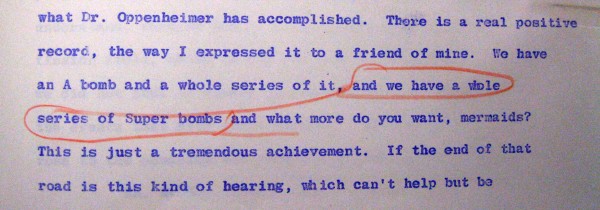

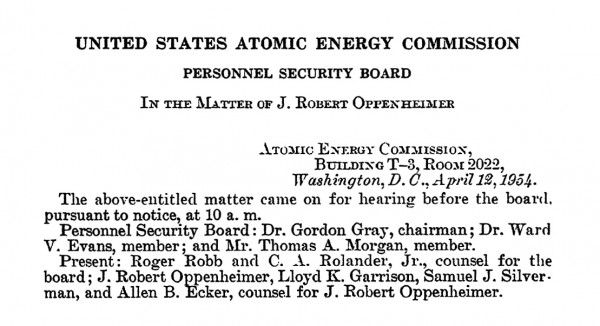

In this category I would also attribute I.I. Rabi’s “mermaids” redaction, mentioned earlier. As published, it was:

We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it, *** and what more do you want, mermaids?

Restored, it is:

We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it, and we have a whole series of Super bombs, and what more do you want, mermaids?

To the censor, the removed section implied, perhaps, that there was no single H-bomb design, but rather a generalized arrangement that could be applied to many different weapons (which were being tested during Operation Castle, which was taking place at the same time as these hearings). This is a tricky distinction for a layman, but important for a weapons designer — and it is the eyes of the weapon designer that the censor feared, in this instance.

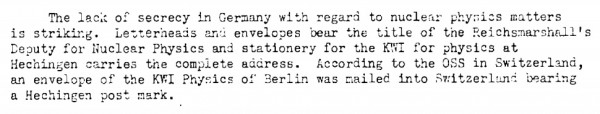

The censor’s fear of foreign scientists scouring the Oppenheimer hearing transcripts for clues as to the H-bomb’s design was not, incidentally, unwarranted. In the United Kingdom, scientists compiled a secret file full of extracts from the (redacted) Oppenheimer transcript that reflected on the nature of the successful H-bomb design. So at least one country was watching. As for the Soviet Union, they detonated their first H-bomb in 1955, having figured out the essential aspects of the Teller-Ulam design by the spring of 1954 (there is still scholarly uncertainty as to the exact chronology of the Soviet H-bomb development, and whether it was an entirely indigenous creation).

The second major category of deletions pertained to Oppenheimer’s role in advising on the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. This involved his participation in Project Vista, a study conducted in 1951-1952 by Caltech for the US Army. Vista was about the defense of continental Europe against overwhelming Soviet ground forces, and Oppenheimer’s section concerned the use of atomic bombs towards this end. (It was named after the hotel that the summer study took place in.)

Oppenheimer’s chapter (“Chapter 5: Atomic Warfare”) concluded that small, tactical fission bombs could be successfully used to repel Soviet forces. In doing so, it also argued against a reliance on weapons that could only be used against urban targets — like the H-bomb. The US Air Force attempted to suppress the Vista report, because it seemed to advocate that the Army into their turf and their budget. It was one of the many things that made the Air Force sour on Oppenheimer.1

In order to emphasize that Oppenheimer was not opposed to the hydrogen bomb on the basis of entirely moralistic reasons, a lot of the discussions at the hearing initiated by his counsel related to his stance on tactical nuclear weapons. They wanted it to be clear that Oppenheimer was not “soft” on Communism and the USSR. Arguably, Oppenheimer’s position was sometimes more hawkish than those of the H-bomb advocates. Oppenheimer wanted a nuclear arsenal that the US would feel capable of using, as opposed to a strategic arsenal that would only lead to a deterrence stalemate.

The debate of strategic arms versus tactical nukes is one that would become a common point of discussion from the 1960s onward, but in 1954 it was still confined largely to classified circles because they pertained to actual US nuclear war plans in place at the time and the future of the US nuclear arsenal. Much of this discussion is still visible in the redacted transcript, but with less emphasis and detail than in the un-redacted original. The essential point — that in the end, the US military pursued both of these strategies simultaneously, and that Oppenheimer was no peacenik — gets filled out a more clearly in the un-redacted version.

Among the sentences that got redacted are long portions that describe the Vista project, its importance, and the fact that it was taken very seriously. It is unfortunate that these were removed, because they would definitely have changed the perception that Oppenheimer was acting on purely “moral” reasons against the hydrogen bomb. Oppenheimer opposed the hydrogen bomb, but he did so, in part, because he advocated making hundreds of smaller fission bombs. Other statements removed is a remark by General Roscoe Charles Wilson about something he heard Curtis LeMay say: “I remember his saying most vigorously that they couldn’t make them too big for him.” One can appreciate why the censor might want to remove such a thing, as a rather unflattering bit of hearsay about the head of the Strategic Air Command. Lest one think that these removals would only help Oppenheimer’s case, many of the other lines removed from Wilson’s testimony concerned the fact that the Air Force did find that they had plenty of strategic targets for multi-megaton bombs — removed, no doubt, because it shed light on US targeting strategy, but the sort of thing that generally went against Oppenheimer’s argument.

Similarly, John McCloy testified that Oppenheimer’s views were fairly hawkish at the time:

I have the impression that he [Oppenheimer], with one or two others, was somewhat more, shall I say, militant than some of the other members of the group. I think I remember very well that he said, for example, that we would have to contemplate and keep our minds open for all sorts of eventualities in this thing even to the point of preventative war.

Did Oppenheimer really advocate preventative nuclear war with the Soviet Union? It’s not impossible — his views in the 1950s could be all over the place, something that makes him a difficult figure to fit into neat boxes. In retrospect, we have made Oppenheimer into an all-knowing, all-rational sage of the nuclear age, but the historical record shows someone more complicated than that. Why would the censor remove the above? Probably because it would be seen as inflammatory to US policy, potentially because it might shed light on actual nuclear policy discussions. In this case, this line potentially could have had a strong impact on the post-hearing memory of Oppenheimer, had it been released, but probably not a positive one.

Lastly, there are a few removals for miscellaneous reasons relating to the conduct of the hearings themselves. As I pointed out at the beginning, when the witnesses at the security hearing took the stand, they were told that their responses would be “strictly confidential,” and not published. This was to encourage maximum candor on their part. When the decision was made to publish the transcript, each of the witnesses were contacted individually to be told this and were asked if there was anything they would not want made public. There is evidence of a few removals for this reason.

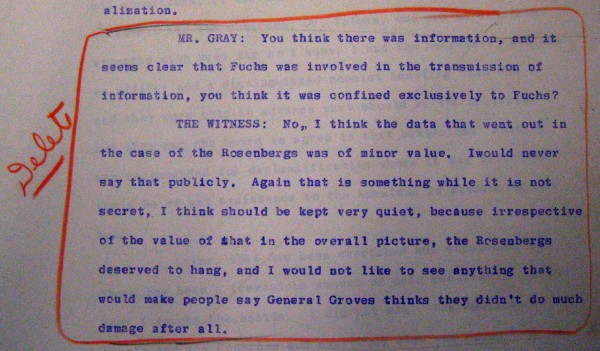

General Leslie Groves, the head of the Manhattan Project during World War II, said a number of things that were not classified but would have been embarrassing or controversial if they appeared in print. For example, he was emphatic that “the British Government deliberately lied about [Klaus] Fuchs,” the German physicist who had been part of the British delegation to Los Alamos and was, as it later became known, a Soviet spy. Groves also opined on the importance of Fuchs’ espionage versus that of the Rosenbergs:

I think the data that went out in the case of the Rosenbergs was of minor value. I would never say that publicly. Again that is something while it is not secret, I think should be kept very quiet, because irrespective of the value of that in the overall picture, the Rosenbergs deserved to hang, and I would not like to see anything that would make people say General Groves thinks they didn’t do much damage after all.

Even Groves’ comment at the time made it clear that this was not something he wanted circulated publicly. Should this information have been removed? It is a tricky question. If Groves had known what he said would be printed, he never would have said any of it. Ultimately this becomes not an issue of classification, but one of propriety. Its inclusion does not affect issues relating to Oppenheimer’s clearance. It is part of a much longer rant on Groves’ part about the British, something he was prone to do when confronted with the fact that the worst cases of nuclear secrets being lost occurred on his watch.

In one slightly smaller category, there is at least evidence of one erroneous, accidental removal. There is a line, on page 129 of the GPO version, which, when restored, looks like this: “Having that assumption in mind at the time Lomanitz joined the secret project, did you tell the security officers anything that you knew about Lomanitz’s background?” The restored material contains nothing classified, or even interesting, and its removal is not noted in the official “concordance” of deleted material produced by the Atomic Energy Commission censor. So why was it removed? Looking at the originals, we find that the entire contents of the deleted material comprise the last line of the page. It looks like it got cut off on accident, and marked as a redaction. Such is perhaps further evidence of the rushed effort that resulted in the transcript being published.

* * *

Does the newly released material give historians new insight into J. Robert Oppenheimer? In my view: not really. At best, they may address some persistent public misconceptions about Oppenheimer, but ones that have long since been redressed by historians, and ones that even the redacted transcript makes clear, if one takes the time to read it carefully and deeply. The general public has long perceived Oppenheimer to be a dovish martyr, but even a cursory reading of the actual transcripts makes it clear that this is not quite right — he was something more complex, more duplicitous, more self-serving.

Oppenheimer’s two TIME magazine covers: as ascendent atomic expert (1948), and casualty of the security state (1954).

If the redacted sentences had been released in 1954, they would have fleshed out a little more of the story behind the H-bomb and behind Oppenheimer’s advocacy for tactical nuclear weapons. They would have emphasized more strongly that Oppenheimer opposed the H-bomb not just for moral reasons, but for technical reasons, and that rather than opposing the development of atomic armaments, Oppenheimer supported them vigorously — and even supported using them in future conflicts. The latter aspect, in particular, might have changed a bit the public’s perception of Oppenheimer at the time. Oppenheimer was not a dove, he was just a different sort of hawk, which somewhat reduces the idea of Oppenheimer as a martyr against the warmongers. This latter notion (Oppenheimer as anti-nuke) is a common perception of Oppenheimer, even today, though much scholarly work has tried to go against this notion for several decades.

The recent declassification of the transcript does not tell us anything we essentially did not already know from other sources, including the many of the wonderfully-researched histories of this period published in recent years by scholars such as Jeremy Bernstein, Kai Bird, David Cassidy, Gregg Herken, Priscilla McMillan, Richard Polenberg, Richard Rhodes, Sam Schweber, Martin Sherwin, and Charles Thorpe, among others. These new revelations do not drastically revise our understanding of Oppenheimer or his security clearing. He looks no more nor less of a “security risk” than he did in the redacted version of the transcripts.

At the same conference where I initially was inspired to search for the hearing transcripts, Polenberg asked the group assembled: how would we remember Oppenheimer today, if he had not had his security clearance stripped after the hearing? His own answer is that we would probably have longer focused on the more negative aspects of Oppenheimer’s personality and perspectives. We’d see him not as a dove, but as a different flavor of hawk. He’d see him as someone who was willing to turn in his friends to the FBI, if it served his interests. We’d see him as someone who, again and again, wanted to be accepted by the politicians and the generals. We would see more of his role as an enabler of the Cold War arms race, not just his attempts at tamping it down. By revoking the clearance, Oppenheimer’s enemies may have crushed his soul, but they made him a martyr in the process.

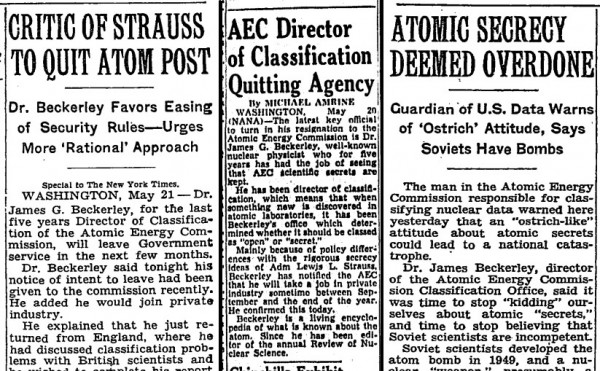

Headlines from 1954 regarding Beckerley and his split with the Atomic Energy Commission — and his turn as a secrecy critic.

But just because these transcripts don’t give us much of a revision on Oppenheimer, or the conduct of his security hearing, doesn’t mean they are not instructive. For one thing, they shed a good deal of light on the process of secrecy itself — and it is only by getting the full story, the record of deletions, that one can pass judgment on whether the secrecy was used responsibility or inappropriately.

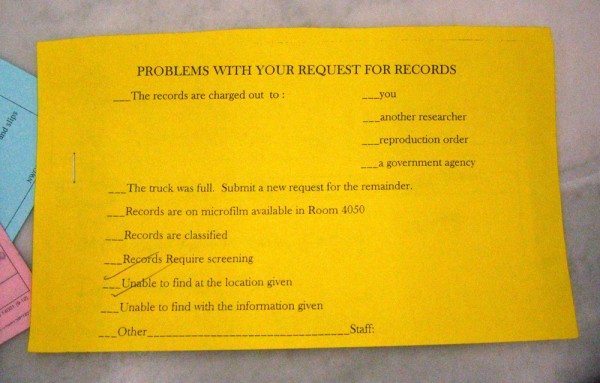

In my view, the erasures appear to have been done responsibly. They do not greatly obscure the ultimate arguments for or against Oppenheimer’s character, and primarily hew to legitimate security concerns for early 1954. The choice of what to remove and what to keep was done not by one of Oppenheimer’s enemies, but by Dr. James G. Beckerley, a physicist who was at the time the Director of the Atomic Energy Commission’s Division of Classification. His initials (“JB”) can be found next to many of the specific deletions in some of the volumes. Beckerley was no rabid anti-Communist or promoter of secrecy. He was a moderate, one who often felt that the AEC’s security rules were highly problematic, and believed that only careful and sane application of classification rules (as opposed to zealous or haphazard) would lead to a stronger nation. As it was, he resigned his job in May 1954, not long after the Oppenheimer hearing, and became an outspoken critic of nuclear secrecy. We do not know Beckerley’s personal opinions on Oppenheimer, but in every other aspect of his work he seems not to be the classification villain that one expects of a Cold War drama.

So it is perhaps not surprising that his deletions from the Oppenheimer transcript are, in retrospect, pretty reasonable, if viewed in context. They do not seem overtly politicized, especially in the way that Beckerley carefully carved up some of the problematic statements so that their ultimate argument still came out, even if the classified details did not. Most were plausibly done in the name of security, according to the security concerns of early 1954. In fact, the amount of discussion of the H-bomb’s development allowed in the final transcript is rather remarkable — very little has in fact been removed on this key topic. A few of the removals, were done in the name of propriety, removed because of the changing status of the transcript from “confidential” to public record. None of the comments removed for non-security reasons seem to have had any bearing on the question of Oppenheimer’s character and loyalty, though they are certainly interesting. Groves’ comments on the Rosenbergs, for example, is completely fascinating — but not relevant to Oppenheimer’s case.

Two frames from a 1961 photo session with Oppenheimer by Ulli Steltzer. “He was shy of the camera and I never got more than 12 shots. It is hard to say which expression is most typical.” More on this image, here.

In this case, I disagree with the conclusions given by the other historians in the New York Times article about the release. I don’t think the removals bolster Oppenheimer’s case, and I don’t think there is any evidence to suggest that the redactions were made to aid the government’s case. We are accustomed to a story about classification that involves bad guys hiding the truth. Sometimes that is a narrative that works well with the facts — classification can, and has often been, abused. But in my (someday) forthcoming book, I argue that part of this impression of “the censor” as a shadowy, faceless, draconian “enemy” is just what happens when we, on the outside, are not privy to the logic on the “inside.”

It is somewhat tautological to say that secrecy regimes hide their own logic by the very secrecy they impose, but it is actually a somewhat subtle point for thinking about how they work. When you are outside of a secrecy regime, you can’t always see why it acts the way it does, and it is easy to see it as an oppositional entity designed to thwart you. Peeling back the layers, which is what historians can do many years after the fact, often reveals a more subtle and complex organizational discussion going on. In the case of these transcripts, it is clear, I think, that Beckerley was trying his best to satisfy both the security requirements of the day regarding the key features of the newly-invented hydrogen bomb, as well as avoid saying too much about US nuclear force postures in Europe. And, just as key, he was juggling the problem of witnesses who had been told their original testimony would be confidential. There is no evil intent in these actions, that I can see.

Did these redacted sentences need to be kept classified for 60 years? Of course not. And by releasing them in full, the Department of Energy explicitly agrees that these transcripts contain nothing classified as of today. But they weren’t being hoarded for decades because of their lasting security relevance — they were just forgotten about. These volumes probably could have been fully declassified at least as early as 1992, and probably would have, had the declassification effort not gotten shelved.

Still, it is important that they are finally released. Even a negative result is a result, and even an empty archive can tell us something positive. Knowing that the un-redacted transcripts contain nothing that would either exculpate, nor incriminate, J. Robert Oppenheimer is itself something to know. Secrecy does not just hide information: it creates a vacuum into which doubt, paranoia, fear, and fantasy are harbored. Removing the secrecy here has, at least, removed one last veil and source of uncertainty from the Oppenheimer affair.

- On Vista, see esp. Patrick McCray, “Project Vista, Caltech, and the dilemmas of Lee DuBridge,” Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences 34, no. 2: 339-370. The Vista cover page image comes from a heavily redacted copy of the report that was given to me by Sam Schweber. [↩]

!["Nuclear C3 [Command, Control, Communication] Transport Systems" — an attempt to characterize the technical, organizational, and political systems needed to actually start nuclear war in the United States today. Source: The Nuclear Matters Handbook, by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs.](https://blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Nuclear-C3-Transport-Systems-600x450.jpg)