When NUKEMAP first got very hot, the Washington Post’s blog declared its popularity a sign of our jittery times. Those were Iranian jittery times, if we remember back all the way to a year ago — today we are jittery again, this time regarding North Korea. And so people are flocking to the NUKEMAP again, trying to see what North Korea’s latest weapons would do to their cities if they were used. I’m almost tempted to push out the new one early, just to take advantage of the interest, but I have faith that we will be jittery again whenever the new one is done. Nuclear jitters aren’t a new thing.

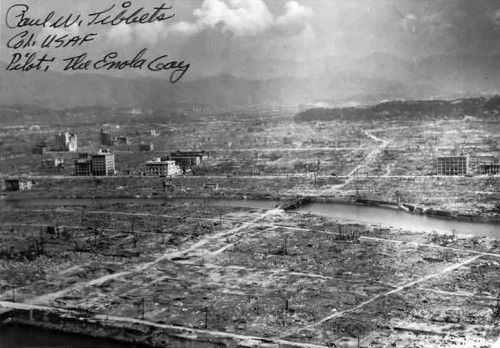

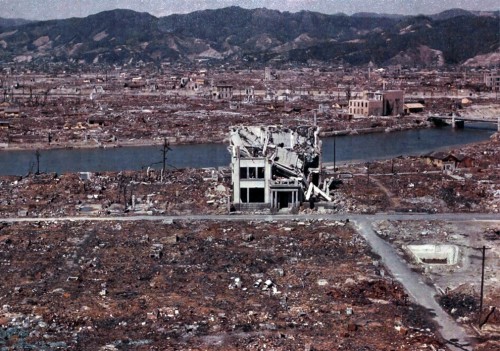

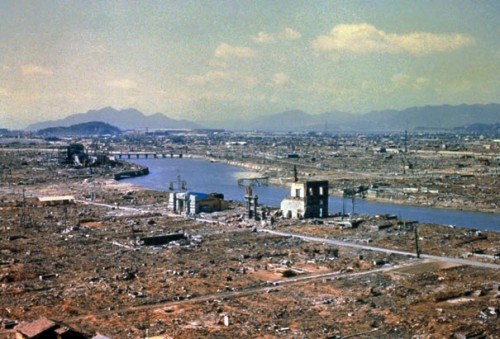

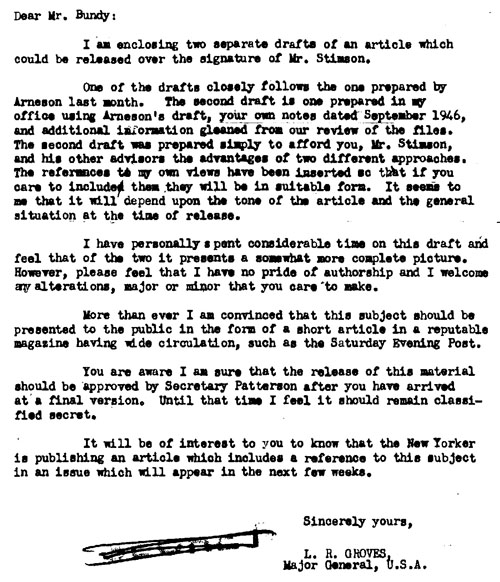

Visualizing nuclear war is an old media pastime. How old? One of the most vivid early depictions of this sort of atomic apocalyptic thinking come from Life magazine’s issue of November 19, 1945 — only a few months after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

From the cover of the issue, you’d have little to suspect about its contents. “Ah, big belts! Fascinating! I love big belts!”

But once you get beyond that, the interior stories are much more interesting. For people interested in World War II and the Cold War, there are a lot of great stories in here: articles about what should be done with postwar China, what was going on in postwar Poland (with some impressive, awful photographs), plus an article on occupied Tokyo (with some amazing illustrations), and another on the OSS (spies!). There was even, at the very end, a reproduction of the Jack Aeby photo of the “Trinity” test, in full color (which was apparently just “orange,” after going through Life’s printing processes).

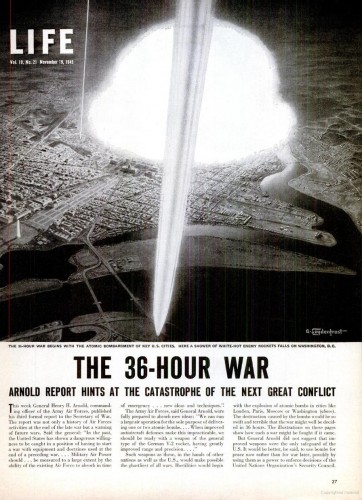

But the real stunner story of the issue was something much more grim. Once you get past a lot of fluffy stuff, you’re greeted with this horror:

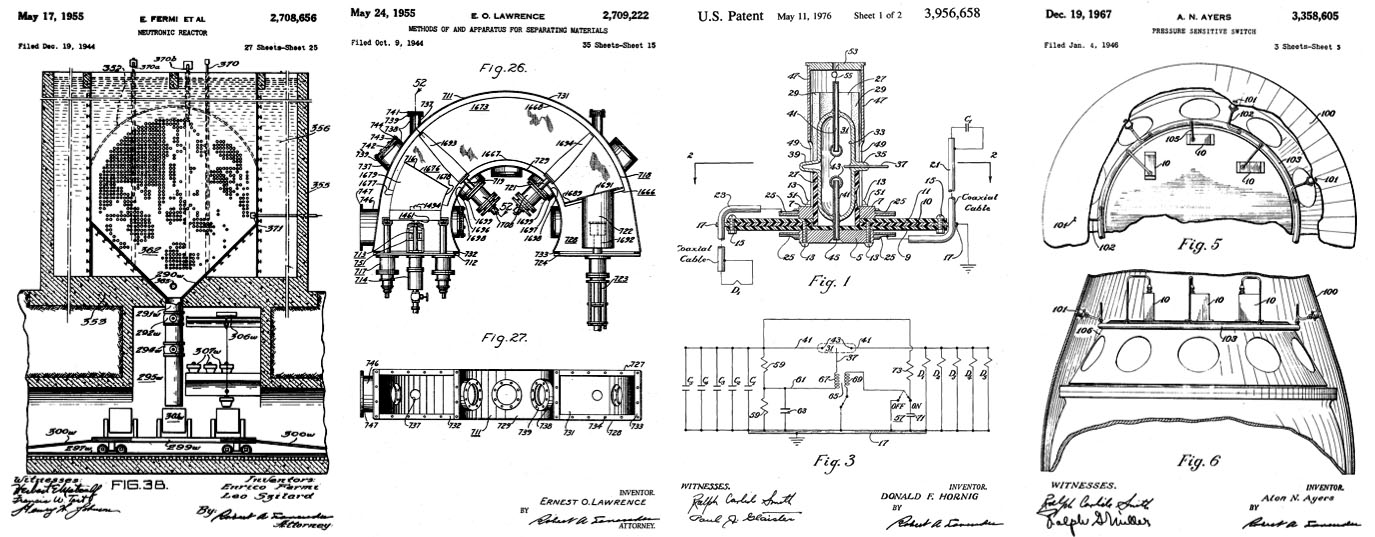

“The 36-Hour War.” This long, feature story is a description of what nuclear war in the future will look like. It was based on a report by General “Hap” Arnold, the chief of the Army Air Forces during World War II and the later founder of Project RAND, which became the RAND Corporation, the epitome of a Cold War think tank. (He was also, incidentally, the guy who gave Curtis LeMay his job in the Pacific theatre.)

The report in question was the “Third Report of the Commanding General of the Army Air Forces to the Secretary of War.” Hunting around a bit, I eventually located a copy of the original online, if you’d like to look at it. It was published only a week before the Life story on it, which is pretty impressive given the illustrations involved in the article. The report is concerned both with summarizing what had happened in the air war during World War II on both the European and Pacific fronts, as well as a concluding section on “Air Power and the Future,” which is the subject of the “36-Hour War” article. Like many strategic bombing advocates, Arnold downplayed the importance of the bomb for World War II, emphasizing that the only reason the atomic bombs, or any bombs, could be delivered at will was because they had already won strategic superiority over the island. It’s the future where Arnold thought atomic weapons will really matter.

And it’s a grim future: rockets plus nuclear weapons equals “the ghastliest of all wars,” according to Life. The implications of ICBMs somewhat understood well over a decade before they were technologically realized.

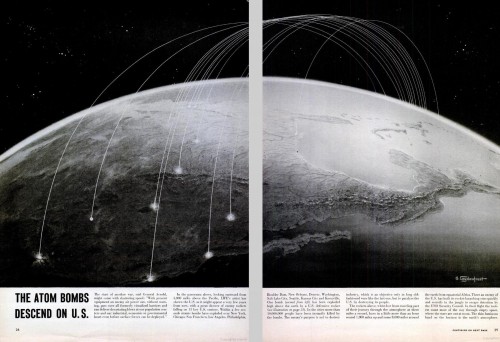

The Life story starts with a large illustration of Washington, DC, getting nuked (hey, at least it’s not New York again, right? But why are they nuking RFK Stadium?), and then follows with a two-page spread showing 13 “key U.S. centers” getting wiped out by the Soviet Union. “Within a few seconds atomic bombs have exploded over New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Boulder Dam, New Orleans, Denver, Washington, Salt Lake City, Seattle, Kansas City, and Knoxville.” (Sorry, Boston, but you didn’t rate! Austin, you are fine for now!) They guess that 10 million people would be killed in the initial attack. “The enemy’s purpose is not to destroy industry, which is an objective only in the long old-fashioned wars like the last one, but to paralyze the U.S. by destroying its people.”

Amusingly, the Life writer suggests that these Soviet missiles came from silos in equatorial Africa, “secretly built in the jungle to escape detection by the UNO Security Council.” Ah, the naiveté of 1945, believing that it would be a taboo of some sort to build ICBM sites! Believing that some kind of international order would be assembled that might affect the conduct of nuclear war! Sigh.

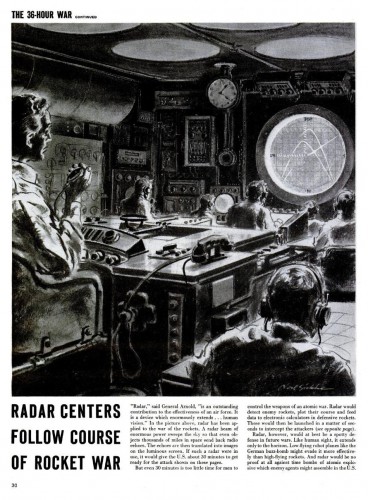

But on the whole the Life story is not bad (except for the ending, which I’ll get to). On the page above, it talks about radar as an early warning technique which they claim would give perhaps 30 minutes warning in the event of an ICBM attack. But they also point out that radar can be evaded by low-altitude missiles and smuggled atomic bobs. And they recognize that 30 minutes is really not that long of a period in time — “even 30 minutes is too little time for men to control the weapons of atomic war.” At best, they suggest, such warning could be used to fire defensive rockets at the incoming rockets, a topic they cover on the next page.

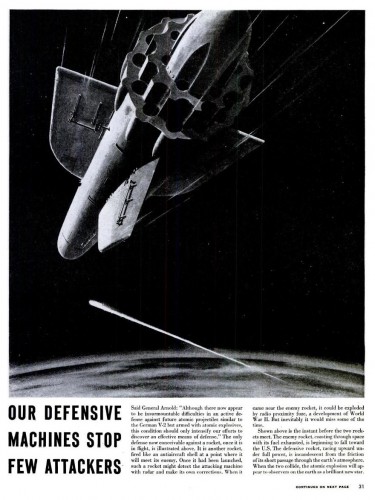

“Our Defensive Machines Stop Few Attackers.” Dang. In this hypothetical future, the US has a missile defense system that works pretty much like you’d expect one to work today — maybe it might destroy a few of them, “but inevitably it would miss some of the time.” The illustration above shows the enemy rocket “coasting through space” in its final descent, with the interceptor missile coming up from the ground. Some nice copy: “When the two collide, the atomic explosion will appear to observers on the earth as a brilliant new star.” It doesn’t actually work that way, but whatever, it’s a nice sentence.

In his report, Arnold outlines three approaches to “defense” against atomic attack. First, you basically try to make sure nobody is making nuclear weapons. Not a bad start, you have to admit. Second, you should try and develop defenses against launched attacks — e.g. missile and bomber defense. A bit more problematic. Third, you redesign the entire country to make it harder to attack with nukes. This is basically the “dispersal” theory of defense — if you don’t have all of your infrastructure and people living in a few, centralized locations, then the vulnerability to all but the most apocalyptic attacks is a lot lower.

But finally, he emphasizes — in the manner befitting a general, I suppose — that the best defense is a good offense. That is, deterrence. And to do that, you need a good second-strike capability, to use the lingo of a later time.

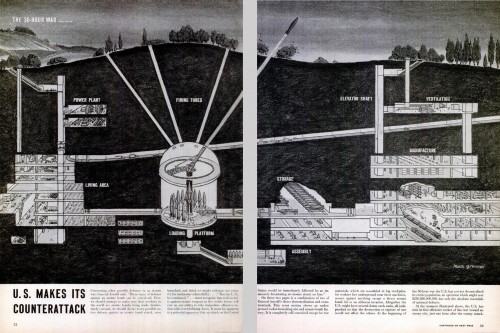

The Life writer and illustrator decided to combine both of these last two ideas, creating a rather amazing fantasy nuclear installation. Take a look at that spread — it’s a huge underground city devoted to producing ICBMs and launching them en masse. It has underground streets and underground cars and underground trains. I’m not sure that Arnold was suggesting anything like this, but it’s pretty amazing. It doesn’t seem very practical, for a lot of reasons (those firing tubes look pretty vulnerable to attack, which would moot the whole installation), but it’s wonderfully imaginative for 1945. Philip K. Dick wrote about crazy installations like this in some of his short stories, but those were written in the 1950s and 1960s.

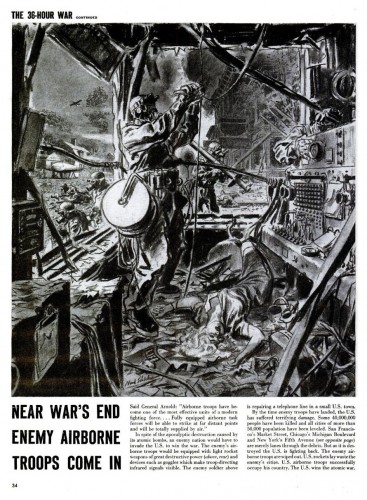

Towards the “war’s end,” enemy troops would show up. This is because, according to the Life writers, “in spite of the apocalyptic destruction caused by its atomic bombs, an enemy nation would have to invade the U.S. to win the war.” Win the war? Here you see a little bit of divergence from what would be a more common narrative: that nuclear war is really just about a “knock-out punch,” as opposed to conventional notions of taking over a country.

The illustration above is pretty interesting. OK, obvious cheesecake fantasy going on there, as gas-masked Soviet thugs step over the somehow-still-beautiful corpse of a telephone operator whose blouse has almost been knocked open by atomic bombs. The Soviet soldiers are attempting to repair the telephone infrastructure and get the country back up to (occupied) speed, and are walking around destroyed streets with bazookas (a less-sung wonder-weapon of WWII). The Life staff estimate that 40 million would be dead at this point “and all cities of more than 50,000 population have been leveled.” New York’s Fifth Avenue is merely a “lane through the debris.”

But, but! Have some hope! Improbably, “as it is destroyed, the U.S. is fighting back. The enemy airborne troops are wiped out. U.S. rockets lay waste the enemy’s cities. U.S. airborne troops successfully occupy his country. The U.S. wins the atomic war.” Wait, what? We won the war? How? A little hand-waving was all that was needed. I know, they nuked all our major cities and landed troops with bazookas, but don’t worry, we managed to (within 36-hours, mind you!) launch a devastating counterattack that included occupying his country. Well. I am relieved and can move on to the article on big belts, no?

Well, hooray. Of course, the country has been reduced to radioactive rubble — “By the marble lions of the New York Public Library, U.S. technicians test the rubble of the shattered city for radioactivity.” But chin up — we won the war!

It’s an amazing place for the article to just… end. A preview of un-defendable, horrible destruction, and then a quick deus ex machina that resolves it. And what a resolution! 40 million dead, no more big cities, but don’t worry, we got ’em back! It’s really not very satisfying. It has the whiff of a heavy, least-minute editorial hand: “we can’t end on such a grim note, and then expect them to just move on to other articles. We’ve gotta win, in the end! Give ’em some hope!”

One wonders: what was the public supposed to take away from this? Support for international control of the bomb? Support for better defenses? Fear of the future? It’s really a wonderful mess, the sort of thing you’d expect only a few months after the bomb made its debut, to be sure. Not all of the clichés had codified, the genre was still new.

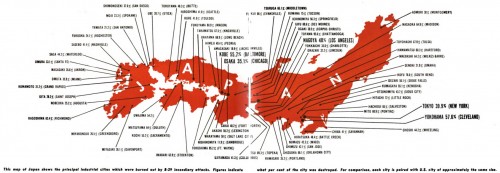

Speaking of which — remember that devastating sequence from Fog of War, where Robert McNamara describes the firebombing of Japan, telling you what percentage of each Japanese city was destroyed, and then telling you an American-sized equivalent? The Arnold report in question did it first, and may have been the source for the data (the percentages and cities seem to match exactly):

Which makes a wonderful full-circle, doesn’t it? Something originally used to brag about performance has now become a touchstone for explaining the barbarity of the Pacific campaign.