Very shortly after the surrender of Japan, American scientists were eager to visit the atomic-bombed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. They were genuinely curious what the effects of atomic bombs were on actual cities — Hiroshima and Nagasaki were rare “experiments” from one point of view, and the scientists wanted the data, so they could start thinking about future atomic wars. How many people died in each city? Were there differences between the cities? How did different types of buildings affect who lived and who died? Did radiation effects really matter? And so on.

American physicist Robert Serber at Nagasaki, September 1945, showing a tree snapped by the blast 4,000 feet from Ground Zero.

Below are excerpts from two unusual accounts I recently ran across relating to the early observations. I say “unusual” in that they contain observations I hadn’t heard before, and that they seem to be rather rare accounts in any event; they aren’t among the more common ones one finds all over the Internet or the history books. These were made a few weeks after the bombs themselves were dropped, owing to the logistical difficulties of the end of the war and the difficulty of getting into the cities. I treasure these sorts of reactions — they usually reveal that even the people who made the bombs and used them were shocked at what they found on the ground, up close. Such impressions are a stark contrast from the view at 30,000 feet.

First, an account of Hiroshima from Colonel (later General) Roscoe C. Wilson, AAF, recollected in 1948. Wilson was part of the first group of Americans into the city. He arrived in Japan in early September 1945, landing in Atsugi:

We landed at Atsugi amid a scene of tremendous activity. The airdrome was battered but fully operational. They then headed to Yokohama.

The countryside was green and peaceful, showing no sign of war. But along the roads women turned their backs, and demobilized soldiers trudged by individually or in small groups with a studied indifference. Only the children greeted us — and they did so with enthusiasm. They made the “V” sign without fail, and shouted “Haroo!” Some of them demanded gum, so it was plain that we were on the route of the 11th [Airborne Division, the first US force in Japan that had arrived not long earlier]. The universally identical greeting of the children could only have been the result of careful schooling.

From there they went to Yokahama:

The outskirts of Yokohama were thoroughly burned out, the people living in huts improvised of galvanized iron sheeting and other salvaged material. It was obvious that community life was being carried on under exceedingly great hardship.

The center of the city, however, was not greatly damaged. Life appeared to be fairly normal, although the absence of any considerable number of people was notable. Through the streets passed mobs of demobilized troops, slogging along in informally organized companies as if the men clung together for mutual support. These motley companies were generally absolutely silent, and appeared to be ignored by the few civilians on the streets.

They stayed in a hotel there for a few days. They moved on, by jeep, to Tokyo:

Tokyo was in frightful condition. Hardly a building was undamaged, and vast areas were destroyed completely. There were no American troops in town, which as yet was “off limits” to the 11th Airborne. We saw an occasional reporter, but otherwise had the conquered city to ourselves. The people were not hostile but exceedingly curious. They swarmed all over our jeep at each stop. Community life was organized and controlled by hordes of gendarmes.

We stopped at the largest of the department stores, which was pitifully stocked. The clerks evidenced no apparent surprise to see us there but rather acted as if they were serving the American tourist of happier days.

At some point they went back to Atsugi, and from there they headed to Hiroshima in a C-54 airplane. Along with Wilson was Brigadier General Thomas Farrell (the local Manhattan Project chief), Brigadier General James B. Newman, Jr., physicist Philip Morrison, and medical officer Colonel Stafford Warren.

We flew over the burned out and ruined cities of Osake and Kobe, arriving over Hiroshima in midmorning. It was apparent that landing on Hiroshima’s airport was impracticable because of the limited runway length and the wreckage which littered the place. We proceeded, therefore, to the military airdrome of Iwakuni, about 20 miles to the south. Here we managed a successful landing despite bomb craters and the wreckage of many aircraft — one of which lay squarely on the runway.

They managed to get a bus to take them to Hiroshima. The bus broke down frequently; it took about 5 hours to make the relatively short journey. They had some issues with the local administration, as they were the first Americans to the city, but it eventually worked out. They headed first to the shrine of Miyajima for the night, on an island. To get there, they had to pass through what Wilson describes as “the Japanese equivalent of Atlantic City — or even Coney Island”:

Nevertheless, when our ferry docked, not a townsman was to be seen on the main street leading from dock to temple. At each street crossing along the main route, however, a gendarme was stationed. In absolute silence, except for the noise we ourselves created, we struggled up the street with our luggage. With the Major leading, we passed the closed shops and houses; as we passed, each gendarme in turn fell silently behind us. I have forgotten how far we walked, but we had quite a platoon behind us when we arrive at the shrine!

Surreal. They stayed at the shrine complex overnight — “the whole shrine area was forested, gloomy and strange to American eyes” — and were given kimonos, which they kept their weapons strapped to. They had a bath and dinner with the priests, then slept — “we retired to our mats with an odd sensation of unreality.”

The next morning the streets were full of people, and they were able to get car rides into Hiroshima.

A good deal has been written about Hiroshima, but no-one can describe adequately the smell — and the flies. The former was noticeable from a distance of several miles: first a faint taint which at certain points in the city became almost overpowering. Even the Japanese, who seem not to notice their nauseating “honey carts,” had their noses bound up while they probed the ruins. And the blue-bottle flies swarmed in clouds. To open a car window was to fill the car with flies. And we climbed through the ruins in individual swarms.

I tramped through Hiroshima unaccompanied, except for a photographer. The able-bodied people paused to watch us, but never displayed any hostility. I went where I wished, except that I was dissuaded from climbing a hill in the southeast part of the city. I was told that was the abode of Yama — God.

From there they eventually made it to Nagasaki. Some awkwardness ensued when they inadvertently “beat” the official arrival force there — “it was very interesting to be on the ‘wrong’ end of a Marine landing” — but otherwise he doesn’t report much.

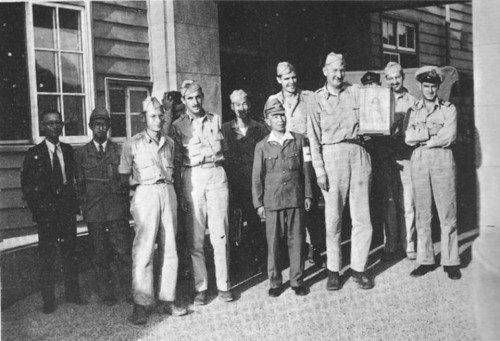

The survey team at Nagasaki. Stafford Warren is the tall man holding a doll given to him as a gift.

Lastly, a brief account of Nagasaki by Colonel Stafford L. Warren, part of the medical contingency. Most of Warren’s account is technical and not extremely interesting, but a few things stuck out. One is an early discussion amongst the Japanese and Warren about the ethics of the bombing:

An ex-Los Angeles Japanese newspaperman appeared at the scene at dinner and interpreted accounts of the Japanese newspaper, of which he carried a copy. It contained a storm of controversy raised by the American correspondents over the ethics of the bomb. The Japanese, of course, were beginning to chime in, but in general, were sitting tight, keeping their own thoughts to themselves about this matter. We discussed this far into the night, and came up with the following arguments…

He then reiterates the common defense of the bombings; that the Japanese were planning to fight through the invasion even though they were beaten, and the bomb allowed them to “save face” and surrender without committing harakiri, many net lives were saved, and so forth. The Japanese with Warren appear to have embraced the argument at the time. I thought it was an interesting thing to have such a discussion at such a time and place. Warren considered the American interest in the argument “as a sort of neurotic self-flagellation.”

Warren also has an interesting discussion of a visit to a temple (maybe the same one Wilson mentioned, above), which Warren says was also the departure site for Kamikaze fighters. Lastly, Warren concludes with this account, which needs no introduction:

I shall never forget walking into the Medical School in Nagasaki about five weeks after the detonation, and, on the landing of the second floor, stepping over the body of a young female partly burned, going down the corridors of an American-designed concrete building like those at home, finding in room after room the laboratory equipment so familiar at home, and on the floors, two or three or more bodies, partly burned, entangled in window frames, and twisted under the benches. They must have been doctors, nurses, technicians, and students.

The school was located half of a mile or three-quarters of a mile from the epicenter, and the walls were thick concrete. In the basement below the main entrance, which was easily accessible, there were four piles of new wooden shoes with pink or red ribbons for the toe. Each pair was beside an empty litter on the floor. Also beside each litter was a smear of what I interpreted to be bloody vomitus or bloody diarrhea. Outside was a pile of bones from the cremated bodies. The pile was about three feet deep and fifty feet in diameter.

Ugh. One of the misleading aspects of the bombing photos is that they look like everyone was just “vaporized”; this wasn’t true. Most of the photos we are familiar with were taken after the bodies were removed and cremated or buried as Warren describes above. You can occasionally find photographs that show you bodies, but they are pretty unpleasant.