In June 1945, Niels Bohr left the United States to return to Copenhagen. He had spent the end of World War II at Los Alamos, mostly as a “father confessor” to the physicists there, but also giving some substantial help on the work of the bomb (he was the one who arbitrated a dispute over which neutron initiator should be used in the implosion bomb).

Rare color photograph of Niels Bohr and his wife Margrethe. Courtesy of the Emilio Segre Visual Archives, from the Dodge Collection.

Ever since he was whisked out of Denmark, Bohr had also been trying to advocate for a postwar international control scheme for nuclear weapons. He tried to convince Winston Churchill, to no effect, and was somewhat successful in convincing Roosevelt on the soundness of such a scheme.

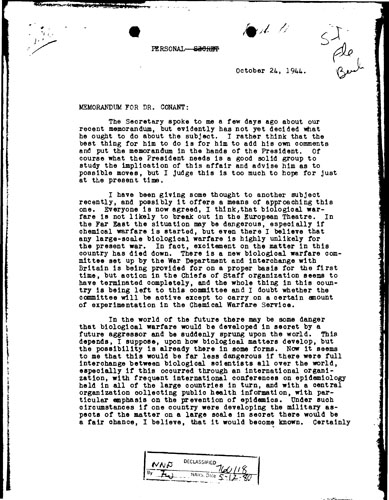

He had a much greater influence on the Los Alamos scientists, like Robert Oppenheimer, and Bohr’s line of thinking can be seen very plainly in the Acheson-Lilienthal Report that Oppenheimer would later contribute to. At the heart of Bohr’s approach was the free exchange of scientific information and scientists — an end of secrecy, he argued, would make it impossible to have a secret nuclear arms race. (This was the same opinion that Vannevar Bush and James Conant had independently come to, as remarked previously on this blog.)

By November 1945, Bohr was feeling quite stressed about how the bomb was being handled. The British Ambassador to the United States, Roger Makins, reported to General Groves on November 7 that:

Bohr is disturbed over the political developments with regard to the atomic bomb. He feels the press treatment of it is creating unnecessary mystification and ill feeling. He cannot understand why so much play is being made over ‘secrets’ which may or may not be shared with the Soviet Union. He considers that there are no essential secrets to the Soviet Government which are not known to them already, and believes that the United States Government’s sole advantage is in production and production experience.1

So in a way it is not surprising that the Soviet Union targeted Bohr as a possible intelligence asset. After all, the “let’s get rid of secrecy” argument is not too far from the “let’s share the bomb” argument, which is what had motivated Klaus Fuchs and Ted Hall and numerous others. It is also not surprising, then, that Bohr agreed to meet with a Soviet physicist, Yakov Terletsky, when he desired a conversation about the postwar atomic situation — Bohr was willing to talk to anyone on such a subject.

But Terletsky was not just a random interested party — he had been sent to Bohr by the NKVD, the organization led by Lavrenty Beria and the predecessor of the KGB.

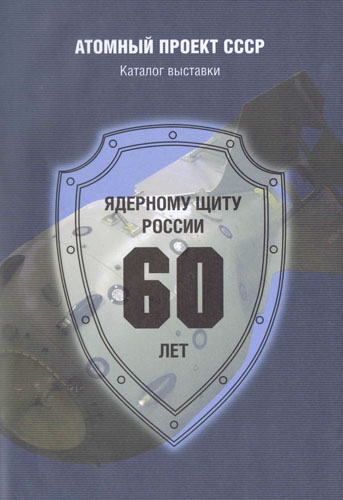

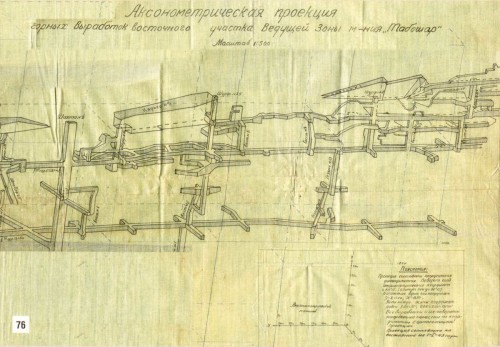

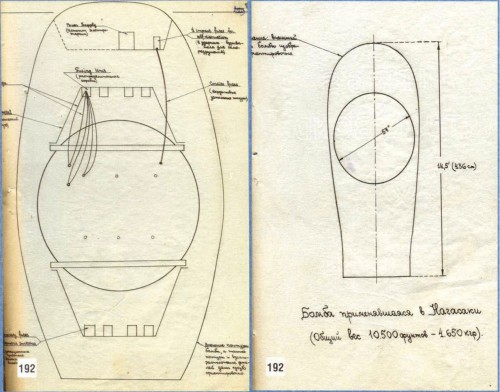

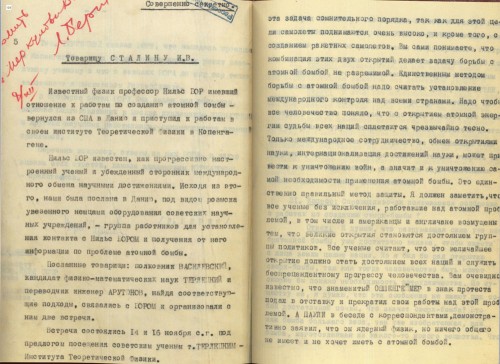

This week’s documents pertain to the Soviet side of the Bohr-Terletsky interview. The one that I have scanned comes from the same Russian nuclear history book I discussed last week, though the copy in the book is incomplete. I have managed to scrounge up copies of these documents from various places on the web and in print and have performed a rudimentary translation on them. (As always, I am happy to have my translations corrected. The original Russian is in the footnotes.)

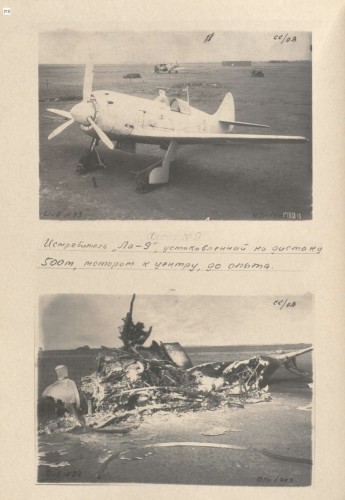

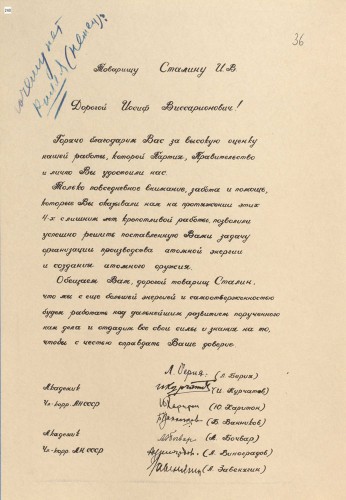

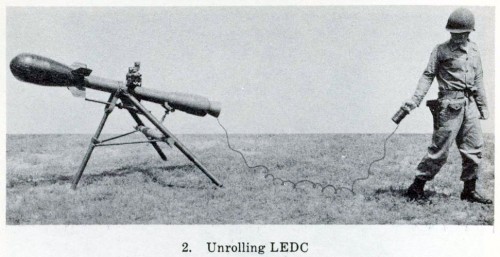

On the left, the letter to Stalin from Beria. On the right, an excerpt from the Bohr-Terletsky interview.

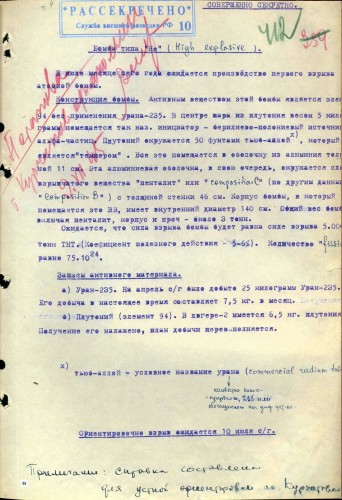

The first document is a letter from Beria to Stalin, reporting on who Niels Bohr is and what they’ve been up to with him. The Wilson Center has this dated in late November 1945, but it may be sometime in early December 1945 as well.2

Label: “Special files”, “Top Secret.” No. 1372-B

[Handwritten:] Make known to Merkulov. L. Beria. 8/X11 [8 Dec.].Comrade STALIN I.V.

The famous physicist, Professor Niels BOHR, who was involved with the work on the atomic bomb, has returned from the USA to Denmark and started to work at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen.

Niels BOHR is known as a progressive-minded scholar and a staunch supporter of the international exchange of scientific achievements. This gave us grounds to send a group of workers to Denmark, under the guise of investigating equipment of Soviet scientific institutions taken away by the Germans, to establish contact with Niels BOHR to seek information on the problem of the atomic bomb.

The comrades sent: Colonel VASILEVSKY, Candidate of Physical and Mathematical Sciences TERLETSKY, and engineer and translator ARUTYUNOV. Having found appropriate approaches, they have got in touch with BOHR and organized two meetings with him.

The meetings were held on November 14 and 16 under the pretext of TERLETSKY visiting Soviet scientists at the Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Comrade TERLETSKY said to BOHR that while in transit in Copenhagen, he felt it his duty to visit the famous scientist, and that he warmly remembered BOHR’s lectures at Moscow University.

During the interviews, Bohr was asked a series of questions prepared in advance in Moscow by Academician KURCHATOV and other scientists involved in the atomic problem.

Attached are the list of questions, BOHR’s answers, and an evaluation of the responses by Academician KURCHATOV.

L. BERIA

Printed in three copies.

Copy No. 1 – addressee.

No. 2 – Secretary of the NKVD.

No. 3 – Section “C”.

Operator Sudoplatov.

Typist Krylov.

Yakov Terletsky was a physicist from Moscow State University. In Richard Rhodes’ Dark Sun, Terletsky described his meeting with Beria the first time, in 1945, in vivid detail:

He was of average height, aging, with a skull that narrowed slightly toward the top, with severe features and no shadow of warmth or a smile. Beria did not give the impression I had expected from seeing his portraits before, of a young, energetic member of the intelligentsia wearing a pince-nez. Everyone sat down at the big conference table. In the middle of the table was a large white marble ash tray in the shape of a polar bear with little ruby eyes. That was the only object on the long table… it was obvious that no one used it.3

Terletsky wasn’t actually the best guy to send — he was a total novice to nuclear physics. His expertise was in statistical physics, and he had less than a week’s understanding of the basics behind nuclear technology. Beria wanted him sent, though, rather than a more experienced physicist. A suspicious master of human intelligence, Beria knew that Bohr would also learn from the exchange — and he didn’t want Bohr to know anything about what the Soviets did or did not know about the bomb.

Terletsky asked Bohr 22 questions. I’ve included a few of the most interesting ones here; these come from the Wilson Center’s Cold War International History Project.

1. Question: By what practical method was uranium 235 obtained in large quantities, and which method now is considered to be the most promising (diffusion, magnetic, or some other)?

Answer: The theoretical foundations for obtaining uranium 235 are well known to scientists of all countries; they were developed even before the war and present no secret. The war did not introduce anything basically new into the theory of this problem. Yet, I have to point out that the issue of the uranium reactor and the problem of plutonium resulting from this — are issues which were solved during the war, but these issues are not new in principle either. Their solution was found as the result of practical implementation. The main thing is separation of the uranium 235 isotope from the natural mixture of isotopes. If there is a sufficient amount of uranium 235, realizing an atomic bomb does not present any theoretical difficulty. … The Americans succeeded by realizing in practice installations, basically well-known to physicists, in unimaginably big proportions. I must warn you that while in the USA I did not take part in the engineering development of the problem and that is why I am aware neither of the design features nor the size of these apparatuses, nor even of the measurements of any part of them. I did not take part in the construction of these apparatuses and, moreover, I have never seen a single installation. During my stay in the USA I did not visit a single plant. While I was there I took part in all the theoretical meetings and discussions on this problem which took place. I can assure you that the Americans use both diffusion and mass-spectrographic installations.

Bohr played his cards close to his chest, here. He told Terletsky nothing that is not already in the Smyth Report. He later explained that you could feed the material from one plant to another, which is also in the Smyth Report. (Did Bohr truly never “visit a single plant”? I’m not sure. This oral history suggests that he did briefly visit Oak Ridge in 1944, but it’s the only account of that I’ve seen, and the interviewee may be mistaken about the timing of that. If Bohr did visit Oak Ridge, it would be an interesting thing in the context of this interview.) Bohr’s line was also very conducive to the control issue — the production of fissile material, he’s arguing, is not a matter of secrecy, but of technology. In this and many other exchanges, one gets the impression that Bohr is trying to convince Terletsky — and his handlers, whom Bohr could not be so naive as to not know existed — of the wisdom of international control.

8. Question: How many neutrons are emitted from every split atom of uranium 235, uranium 238, plutonium 239 and plutonium 240?

Answer: More than 2 neutrons.

9. Question: Can you not provide exact numbers?

Answer: No, I can’t, but it is very important that more than two neutrons are emitted. That is a reliable basis to believe that a chain reaction will most undoubtedly occur. The precise value of these numbers does not matter. It is important that there are more than two.

A direct technical question with an evasive answer. Did Bohr know the precise number of neutrons? Undoubtedly. Would he tell? No. Why not? Because “the precise value” actually does matter for critical mass calculations. His dismissal of the importance of this value constrains his discussion, again, almost to the level of the Smyth Report. (He may have gone a tiny bit beyond, but not in a serious way. The Smyth Report does not say the amount of neutrons released per fission, but it does say that it was known in 1940 that it was between 1 and 3. Obviously it couldn’t have been less than two, though, if the reactor and bomb were going to work. So Bohr has not really said much, here.)

15. Question: Does the pile begin to slow as the result of slag formation in the course of the fission of the light isotope of uranium?

Answer: Pollution of the pile with slag as the result of the fission of a light isotope of uranium does occur. But as far as I know, Americans do not stop the process specially for purification of the pile. Cleansing of the piles takes place at the moment of exchange of the rods for removal of the obtained plutonium.

This is an odd question with a confused answer. It’s a reference to so-called “Xenon-poisoning” in the first industrial-sized nuclear reactors at Hanford. Xenon-135, a fission product, builds up as the reaction commences. However, it is also a neutron absorber, so the reactions tend to slow down as more of the isotope is created. This is the “pollution” Bohr refers to. It was a major issue at Hanford. The way to fix it is to cycle through the fuel loads more often. So Bohr’s answer is not very clear, though he may have just been ignorant on Hanford issues.

Xenon-poisoning was mentioned in the first edition of the Smyth Report, but deleted from subsequent re-printings by General Groves. The discrepancy was noticed by the Soviet translators — yet another case where an attempt at secrecy actually highlighted what was meant to be hidden.

19. Question: Of which substance were atomic bombs made?

Answer: I do not know of which substance the bombs dropped on Japan were made. I think no theorist will answer this question to you. Only the military can give you an answer to this question. Personally I, as a scientist, can say that these bombs were evidently made of plutonium or uranium 235.

I’m pretty sure Bohr is lying here. It seems highly unlikely that he was unaware of the differences between the gun and implosion bombs, or the fact that there were both uranium-235 and plutonium bombs used.

20. Question: Do you know any methods of protection from atomic bombs? Does a real possibility of defense from atomic bombs exist?

Answer: I am sure that there is no real method of protection from atomic bomb. Tell me, how you can stop the fission process which has already begun in the bomb which has been dropped from a plane? It is possible, of course, to intercept the plane, thus not allowing it to approach its destination — but this is a task of a doubtful character, because planes fly very high for this purpose and besides, with the creation of jet planes, you understand yourself, the combination of these two discoveries makes the task of fighting the atomic bomb insoluble.

We need to consider the establishment of international control over all countries as the only means of defense against the atomic bomb. All mankind must understand that with the discovery of atomic energy the fates of all nations have become very closely intertwined. Only international cooperation, the exchange of scientific discoveries, and the internationalization of scientific achievements, can lead to the elimination of wars, which means the elimination of the very necessity to use the atomic bomb. This is the only correct method of defense.

I have to point out that all scientists without exception, who worked on the atomic problem, including the Americans and the English, are indignant at the fact that great discoveries become the property of a group of politicians. All scientists believe that this greatest discovery must become the property of all nations and serve for the unprecedented progress of humankind. You obviously know that as a sign of protest the famous OPPENHEIMER retired and stopped his work on this problem. And PAULI in a conversation with journalists demonstratively declared that he is a nuclear physicist, but he does not have and does not want to have anything to do with the atomic bomb. …

We have to keep in mind that atomic energy, having been discovered, cannot remain the property of one nation, because any country which does not possess this secret can very quickly independently discover it. And what is next? Either reason will win, or a devastating war, resembling the end of mankind.

Ah, Bohr really got going here — Terletsky got him on a topic where he could pontificate very freely (notice the length at which he speaks here, compared to the technical questions).

21. Question: Is the report which has appeared about the development of a super-bomb justified?

Answer: I believe that the destructive power of the already invented bomb is already great enough to wipe whole nations from the face of the earth. But I would welcome the discovery of a super-bomb, because then mankind would probably sooner understand the need to cooperate. In fact, I believe that there is insufficient basis for these reports. What does it mean, a super-bomb? This is either a bomb of a bigger weight then the one that has already been invented, or a bomb which is made of some new substance. Well, the first is possible, but unreasonable, because, I repeat, the destructive power of the bomb is already very great, and the second — I believe — is unreal.

This is an odd question to ask, with an even odder answer. That the idea of a “superbomb” (сверхбомбы, here) was out and about by this point is something I’ve remarked on previously. They’re basically asking Bohr what he knows about the idea of a hydrogen bomb, something that was explored during the Manhattan Project. In any case, Bohr’s answer is very misleading — whether because he was being deliberately misleading or because he was just uninformed, I don’t know. But his dismissal of the idea that you could optimize bomb design for a larger explosion, or that you could use other materials for nuclear explosions, is completely incorrect.

22. Question: Is the phenomenon of overcompression of the compound under the influence of the explosion used in the course of the bomb explosion?

Answer: There is no need for this. The point is that during the explosion uranium particles move at a speed equal to the speed of the neutrons’ movement. If this were not so the bomb would have given a clap and disintegrated as the body broke apart. Now precisely due to this equal speed the fissile process of the uranium continues even after the explosion.

This last question is a puzzler. It’s unclear exactly what was asked here (something is lost in multiple translations), but it sounds a lot like they are asking about whether compressing fissile material is necessary. Bohr doesn’t really answer it — he basically says that the bomb explodes a bit after it runs its reaction (which is true, but not super relevant, I don’t think), when he knows, from being at Los Alamos, that compression is used during the implosion of the bomb. But again, it’s hard to make sense of either the question or the response.

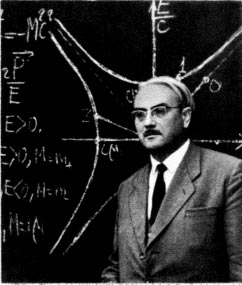

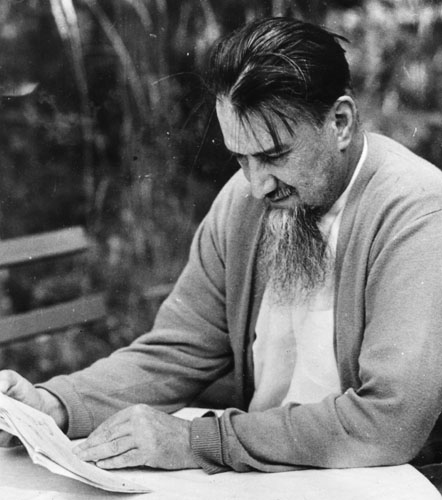

Kurchatov in the 1950s. Photo credit: Ioffe Physical Technical Institute, courtesy AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

Lastly, we turn towards an evaluation of Bohr’s responses by Igor Kurchatov, a.k.a. “The Beard,” the head scientist on the Soviet bomb program. This is dated “December 1945,” which is why I am suspicious about the November dating of the Beria document above (since this was attached to it).4

EVALUATION

Answers given by Professor Niels BOHR

on questions relating to the atomic problemNiels Bohr was given two sets of questions:

1. Concerning the main directions of work.

2. Containing specific physical data and constants.

BOHR gave some answers to the first group of questions. BOHR gave a definitive answer to the question on the U.S. methods used for producing uranium-235, which has quite satisfied Professor [Isaak] KIKOIN, Corresponding Member of Academy of Sciences, who asked this question.

Niels BOHR made a crucial point about the effectiveness of uranium in the atomic bomb. This comment should be subjected to theoretical analysis, which should be entrusted to professors LANDAU, MIGDAL and POMERANCHUK.

Academic KURCHATOV

December 1945.

Kurchatov’s analysis is interesting. Bohr’s “definitive” answer on uranium-235 production is only significant if you distrust the Smyth Report. (And it makes sense that the Soviets would distrust it.) It is really unclear to me what the “effectiveness” comment is referring to — my assumption is that it refers to question 22, which is hard to parse in any event.

What’s most interesting to me about Kurchatov’s analysis is how positive it is, when Kurchatov surely must have known that Bohr wasn’t telling them much — either because he didn’t know it, or because he didn’t want to tell them.

And yet, he’s still writing up the operation as a big success. My guess is that he’s trying to make Beria happy about everyone who participated — Bohr, Terletsky, and so on. Bohr didn’t give them much information, but it wasn’t really Terletsky’s fault.

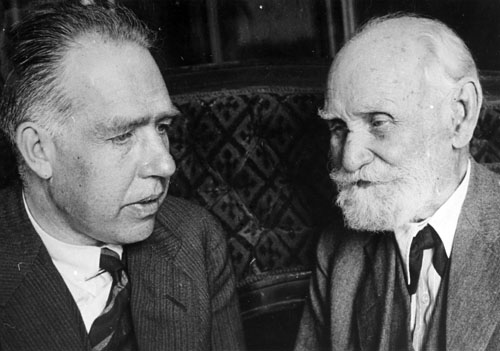

Bohr and Ivan Pavlov, the famous Russian physiologist, probably in the 1920s or 1930s. One wonders what they would have discussed. Courtesy of the Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

But let’s flip this around: What did Bohr learn from Terletsky? If Bohr took seriously that Terletsky was representative of the interest of Soviet physicists in the bomb, he probably would have assumed that they didn’t know much. The questions Terletsky asked do not reveal very much knowledge on the subject matter, and certainly don’t reveal insight from intelligence sources (number 22 might hint at it, but that’s it, and even then, it’s not very clear).

In a sense, Beria’s decision to send Terletsky was spot-on. Bohr wasn’t going to tell the Soviets anything that wasn’t already publicly known. Beria couldn’t have known that from the beginning, but sending someone like Terletsky would have been a good way to find out for sure — if Bohr had been indiscreet or seemed like a source to be “cultivated,” more contact could have followed later. Bohr’s refusal to give precise numbers on the neutron emissions was his most direct case of clearly not cooperating. They likely would have been a clear signal that Bohr either didn’t know technical details, or that he wasn’t interested in divulging them.

Had Beria sent someone deeper into the atomic problem (like Khariton or Zel’dovitch) the line of questioning likely would have shown Bohr that they knew much more than they were supposed to. Would someone who really knew about the bomb project be able to ask those simple questions with such a straight face?

What’s wonderful about reading this in retrospect is that we know that both Bohr and the Soviets knew more than they let on. This “interview” (or “interrogation”) is a tremendous dance of shadows — two people trying to get information without giving too much away. And like many such exchanges, neither side likely learned very much.

Amusing Soviet fact of the day: During World War II the Red Army’s in-house counter-espionage unit — which served mostly to root out perceived enemies of the people within the Army itself — was called SMERSH (СМЕРШ), an acronym of the phrase “Death to Spies!” Stalin coined this exceptionally silly name himself.

- Roger Makins to Leslie R. Groves (7 November 1945), Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Folder 11: “Correspondence with Foreign Nations,” Roll 2, Target 5. [↩]

-

Грифы: “Особая папка”, “Совершенно секретно”. No. 1372-Б

Ознакомить тов. Меркулова В. М. Л. Берия. 8-Х11Товарищу СТАЛИНУ И.В

Известный физик профессор Нильс БОР, имевший отношение к работам по созданию атомной бомбы, вернулся из США в Данию и приступил к работам в своем институте теоретической физики в Копенгагене.

Нильс БОР известен как прогрессивно настроенный ученый и убежденный сторонник международного обмена научными достижениями. Исходя из второго, нами была послана в Данию, под видом розыска увезенного немцами оборудования советских научных учреждений, группа работников для установления контакта с Нильсом БОРОМ и получения от него информации по проблеме атомной бомбы.

Посланные товарищи: полковник ВАСИЛЕВСКИЙ, кандидат физико-математических наук ТЕРЛЕЦКИЙ и переводчик инженер АРУТЮНОВ , найдя соответствующие подходы, связались с БОРОМ и организовали с ним две встречи.

Встречи состоялись 14 и 16 ноября с. г. под предлогом посещения советским ученым т. ТЕРЛЕЦКИМ Института теоретической физики.

Тов. ТЕРЛЕЦКИЙ сказал БОРУ, что, находясь проездом в Копенгагене, счел своим долгом нанести визит известному ученому и что о лекциях БОРА до сих пор тепло вспоминают в Московском университете.

В процессе бесед БОРУ был задан ряд вопросов, заранее подготовленних в Москве академиком КУРЧАТОВЫМ и другими научными работниками, занимающимися атомной проблемой.

Перечнь вопросов, ответы на них БОРА, а также оценка этих ответов, данная академиком КУРЧАТОВЫМ, прилагаются.

Л. БЕРИЯ

Отпечатано в 3 экз.

Экз. No. 1 – адрестау.

No. 2 – Секр. НКВД СССР.

No. 3 – Отдел “С”.

Исполнитель Судоплатов.

Машинистка Крылова.[↩]

- Dark Sun, 218-219. [↩]

-

ОЦЕНКА

Ответов, данных профессором Нильс БОР

на вопросы по атомной проблемеНильсу БОРУ были заданы две группы вопросов:

1. Касающиеся основных направлений работ.

2. Содержащие конкретные физические данные и константы.

Определенные ответы БОР дал по первой группе вопросов. БОР дал категорический ответ на вопрос о применяемых в США методах получения урана-235, что вполне удовлетворило члена-корреспондента Академии наук проф. КИКОИНА, поставившего этот вопрос.

Нильс БОР сделал важное замечание, касающееся эффективности использования урана в атомной бомбе. Это замечание должно быть подвергнуто теоретическому анализу, который следует поручить профессорам ЛАНДАУ, MIGDAL и ПОМЕРАНЧУК.

Академик КУРЧАТОВ.

Декабрь 1945 года.[↩]