Edward Teller’s relationship to Cold War loyalty/security hearings is, in a word, infamous.

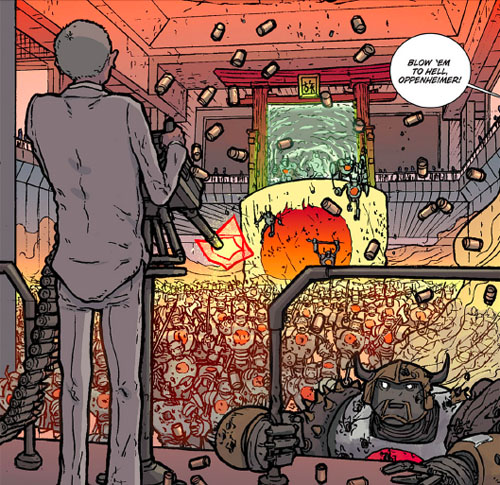

Teller famously was one of the few academic scientists to testify against J. Robert Oppenheimer in 1954. The most damning part of Teller’s testimony was thus:

Q. To simplify the issues here, perhaps, let me ask you this question: Is it your intention in anything that you are about to testify to, to suggest that Dr. Oppenheimer is disloyal to the United States?

A. I do not want to suggest anything of the kind. I know Oppenheimer as an intellectually most alert and very complicated person, and I think it would be presumptuous and wrong on my part if I would try in any way to analyze his motives. But I have always assumed, and I now assume that he is loyal to the United States. I believe this, and I shall believe it until I see very conclusive proof to the opposite.

Q. Now, a question which is the corollary of that. Do you or do you not believe that Dr. Oppenheimer is a security risk?

A. In a great number of cases I have seen Dr. Oppenheimer act—I understood that Dr. Oppenheimer acted in a way which for me was exceedingly hard to understand. I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated. To this extent I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more.

In this very limited sense I would like to express a feeling that I would feel personally more secure if public matters would rest in other hands.

Personally, I’ve long thought that the flack that Teller got for this has been a bit overdone. Teller goes out of his way to keep his testimony pretty respectful and pretty mild, and was hardly the only scientist who opposed Oppenheimer. Behind the scenes Teller did a lot worse stuff than this. There’s no evidence that Teller’s testimony really directed the Gray Board or the AEC in directions they weren’t already going. Oppenheimer didn’t lose his security clearance because of Teller. He lost it because he made fairly large political enemies (much larger than Teller), and because he came off as inconsistent and problematic when he got on the witness stand.

“Don’t Fence My Baby In.” Cartoon by Bill Mauldin, Chicago Sun-Times, 1963; no doubt a reference to Teller’s opposition to the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

Still, I understand why Teller gets so much opprobrium: he turned on a (former) friend, and he did so largely because of differences in intellectual opinions. This, coupled with his vigorous advocacy for excessively large weapons and extremely hawkish positions with respects to the arms race, makes him a fairly unlovable figure. But it was Teller’s association with one of the more disturbing “loyalty” hearings that really sealed his position as one of the “bad guys” of the atomic age.

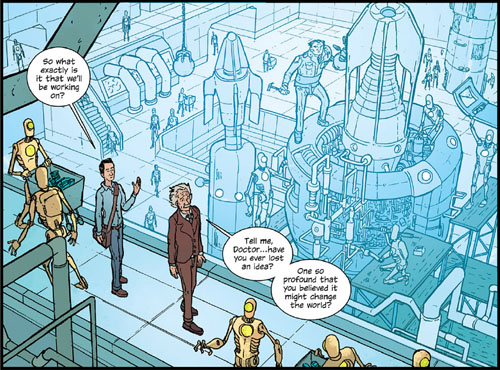

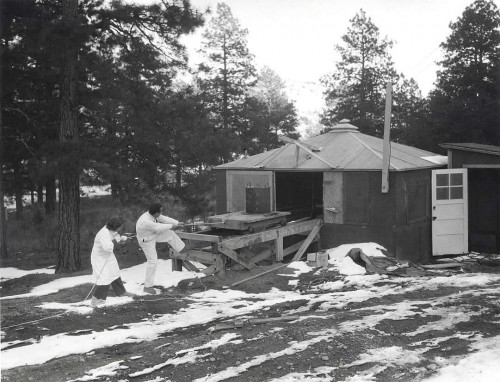

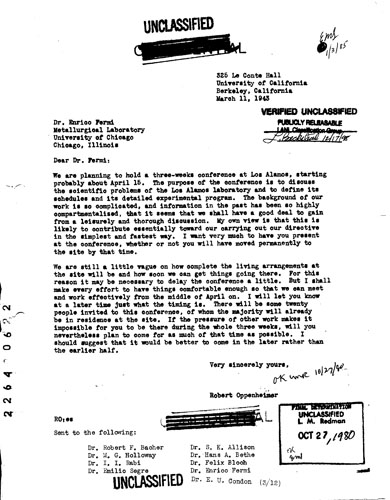

So I was a bit surprised when I came across this week’s document — a letter from Teller to Norris Bradbury (Oppenheimer’s successor as the director of Los Alamos) from 1948. In it, Teller contemplates coming back to Los Alamos, at Bradbury’s request, having retreated to the University of Chicago at the end of World War II.

Teller was enthusiastic about coming back to the lab, even though he claimed more interest in abstract theoretical physics:

The main reason that attracts me is the great importance of the work on the atomic bomb. I fully realize the menacing international situation and I believe that the United States must develop its military strength to the utmost if we are not to succumb to the danger of communism.

Nothing surprising there — that’s classic Edward Teller for you. Fair enough. But then Teller changes course dramatically from the stereotype:

In considering my proposed position in Los Alamos during the past weeks, I have been disturbed by a problem which can be best summarized by the words “loyalty investigation.”

Wait, what? That’s right: Dr. Strangelove himself was anxious about “loyalty” getting in the way of a security clearance.

Teller continued:

I fully realize the necessity or checking improper dissemination of information. I am convinced of the necessity of checking Russian attempts to obtain classified information about atomic developments from our country. But clearance cases that have occurred in the last months have raised questions in my mind concerning the interpretation or the word “loyalty.”

I feel certain that in my actions and intentions I am loyal to the United States. More specifically I am certain that I would under no conditions want to live under a communist dictatorship and that I shall in every way try to oppose communist-world domination. This, indeed, is the reason why I consider coming to Los Alamos.

On the other hand, I do not want to lose the privilege of reading any publication about Russia — favorable or unfavorable. I consider it my right to make up my own mind about political questions and I feel that it is my intellectual duty to study all sides of a question that is as important as the question or communism. … I believe, however, that I never could understand the nature or the communist system and could never be convinced of the magnitude of communist danger it I did not inform myself of the arguments in favor of communism as well as of the reasons to reject that system. I should certainly not like to put myself into a position where it would be considered improper for me to read literature favorable to Russia or even to read publications which are Russian propaganda.

In other words, Teller is afraid that the “loyalty” will be assessed in a clunky way , by just looking at what books someone reads, or — more to the later relevance of Oppenheimer — who they “associate” with.

I furthermore do not want to be in a position where it would be necessary for me to avoid an individual merely because he is a convinced communist. It is of course clear that I never discuss classified material with any unauthorized person, whether I agree with his political views or not. In the past I have associated occasionally with individuals whom I believed to be communists. In the following I want to describe to you these cases.

Teller then describes two cases, a Mr. A and a Mr. B (he does not identify them by name), where his friends have had dubious views. He then generalizes the problem:

It is quite possible that some of my other friends or acquaintances had connections with the communist party. I have not discussed politics with all of them and some of them may have been reticent on purpose. In no other cases did I have as clearcut evidence as in those mentioned above.

I certainly do not want to feel that in order to behave properly I must scrutinize the convictions or my friends. I furthermore want to feel free that in case I know of a person that believes in communism I need not avoid him for that reason alone.

Reading Russian literature probably wouldn’t get the FBI too irritated with you, in and of itself. (Subscribing to Communist newspapers is another story.) But acquaintances were definitely a source of judgment — and Teller probably knew this, having followed the well-publicized security issues of other scientists in the late 1940s. (On these, Jessica Wang’s American Science in an Age of Anxiety remains the canonical source.)

Bradbury did write back to Teller in November. He told Teller that what he described would not be a problem… but, if Teller had the chance, the FBI would love the names of that “Mr. A” and “Mr. B” he mentioned, just in case:

This is entirely independent of the Atomic Energy Commission and is only for the purpose of making sure that the position of the United States is as strong as possible with respect to possible unfriendly individuals. The execution of this suggestion is entirely at your discretion, but you can be assured that any information of this nature which you may give the FBI would be kept entirely confidential, that your name would not be involved, and that the rights of the individual concerned would be fully protected.

Thus Teller gets off the hook, but it is not too subtly implied that a truly “loyal” citizen would provide the names. Such is the way of “loyalty” — you can associate with whomever you want… as long as you’re willing to sell them out.

Teller isn’t unique in this respect. Oppenheimer did the same thing; anyone who was anyone in the high Cold War reported on their acquaintances. Oppenheimer’s own FBI file is full of “friends” who informed on his every opinion given at his famous cocktail parties. (Teller’s FBI file is mostly devoted to whether he is the same “Edward Teller” who once taught a class on Marxism in New York City.)

But it’s interesting to see that Teller too recoiled at the idea of “loyalty” as something that can be easily measured and assessed. And indeed, as we’ve seen above, Teller went out of his way to express his belief that Oppenheimer was in no way disloyal. But he didn’t see that as being synonymous with not being a security risk.