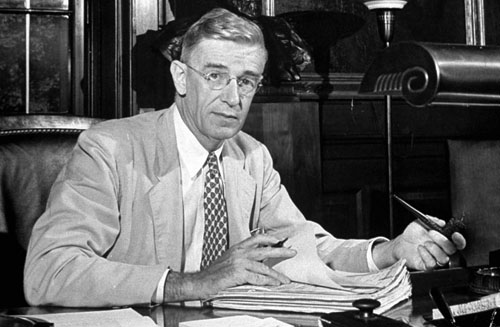

At the end of 1944, Vannevar Bush and James Conant, the atomic administrators at the Office of Scientific Research and Development and the National Defense Research Committee, were starting to worry about what to do about the bomb. Not in the near term — but what to do about it after World War II.

How do you regulate a totally new technology — both domestically and internationally? Where do you begin, in thinking about it? Especially when the technology in question is the atomic bomb, a weapon that seemed to pose insuperable existential questions and seemed capable of revolutionizing not only war, but the idea of nation-states themselves?

Bush and Conant, for their part, spent a lot of time looking for analogies: using their experience with other regulatory regimes to inform their understanding of an atomic regulatory regime.

This wasn’t their first technological rodeo: Bush had been deeply involved in radio technology regulation in the 1920s, and Conant was a veteran hand when it came both to chemical warfare and, as it happened, the regulation of rubber. (One of the many control approaches they pursued was that of patents, which I’ve written about pretty extensively.)

But even more pertinently, they worked openly on the problem of regulating biological warfare, with the secret goal of using this as a trial balloon for the types of regulations they’d recommend for the atomic bomb.

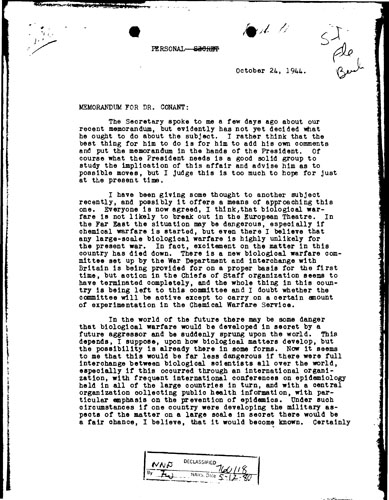

The weekly document is a letter from Vannevar Bush to James B. Conant, dated October 24, 1944, on the problem of the long-term control of biological warfare— not just because Bush thought it was important, but because he thought it would help make sense of what to do with the bomb.

Bush started it off by referencing a “recent memorandum” to the Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, which they had sent at the end of September. In that memo, Bush and Conant warned that secrecy wouldn’t be a long-term international solution for the bomb, and strongly recommended that Stimson start seriously making moves towards some means of international control of the bomb. Stimson wasn’t yet sure, though (he would later become convinced).

He then continued:

I have been giving some thought to another subject recently, and possibly it offers a means of approaching this one [the bomb]. Everyone is now agreed, I think, that biological warfare is not likely to break out in the European Theatre. In the Far East the situation may be more dangerous, especially if chemical warfare is started, but even there I believe that any large-scale biological warfare is highly unlikely for the present war. In fact, excitement on the matter in this country has died down. …

In the world of the future there may be some danger that biological warfare would be developed in secret by a future aggressor and suddenly sprung upon the world. This depends, I suppose, upon how biological matters develop, but the possibility is already there in some forms.

Bush considers biological warfare to be somewhat of a dead, but scary, letter. Since it was looking like it would be irrelevant to the current conflict (Bush either didn’t know or didn’t consider the BW use by Japan again the Chinese to fall under this assessment), it could be talked about relatively openly. Thus they could explore some of the salient questions about the atomic bomb before the bomb itself was outside of secrecy. Pretty clever, Dr. Bush.

The exact plan Bush was shooting around was as follows:

Now it seems to me that this would be far less dangerous if there were full interchange between biological scientists all over the world, especially if this occurred through an international organization, with frequent international conferences on epidemiology held in all of the large countries in turn, and with a central organization collecting public health information, with particular emphasis on the prevention of epidemics. Under such circumstances if one country were developing the military aspects of the matter on a large scale in secret there would be a fair chance, I believe, that it would become known.

Certainly any county that did not have ideas of aggression somewhere in the back of its mind would be inclined to join such an affair genuinely and open up the interchange, unless indeed there is more duplicity in the world than I am inclined to think. It may be well worth while to attempt to bring this about.

The plan, then, was to have complete scientific interchange as a regulatory mechanism. If the work being done is talked about openly, then there would be no “secret arms race.”

This is an idea that was quite popular in many circles at the time regarding the bomb, as well. Niels Bohr in particular argued very strongly for this form of “international control”: if you got rid of secrecy, he argued, you’d be able to see what everyone was doing, and if all the relevant scientists dropped of the face of the Earth all of the sudden, you’d know they were developing WMDs.

It’s an optimistic idea, one which puts a little too much stock, I think, in the communicative power of scientific exchange. An invitation to a conference is not a verification mechanism. It doesn’t take into account the ability of states to stage entirely shadow programs, or to have scientists who are happy to be duplicitious to other scientists. It somewhat naively subscribes to the idea of a transnational scientific community that is “above” politics. Even by World War II such a notion should have been seen as somewhat old fashioned; certainly the Cold War showed it to be.

Still, the goals were laudable, and as a way for thinking through international scientific control, it wasn’t the worst approach. Bush and Conant’s greatest fear with respects to the bomb was a “secret arms race.” They really thought this could not end with anything but mass destruction for all. At least a non-secret arms race, they argued, would keep people from doing anything too stupid.

Bush closes the letter with this wonderful paragraph:

You will readily see that I have in mind more than meets the eye, and am thinking of an entering wedge. However, I would very much like to explore with you this particular thing on its own merits, and also from the standpoint of what its relationship might be to other matters.

Bush was interested in the control of biological warfare, but he was more interested in thinking about the bomb. Biological warfare would be his “entering wedge” in approaching the issue of scientific control, knowing that soon enough they’d be worrying about something he considered even bigger.