The job of the document reviewer is the job of a censor: they look at documents that might be released and, based on a declassification guide and their own judgment, decide what should be made public and what should not. Today such redactions are usually done with computer programs like Adobe Acrobat, which has an apparently rigorous “redaction” mode that allows you to essentially draw white boxes over a page and have the data underneath them be totally expunged, like so:

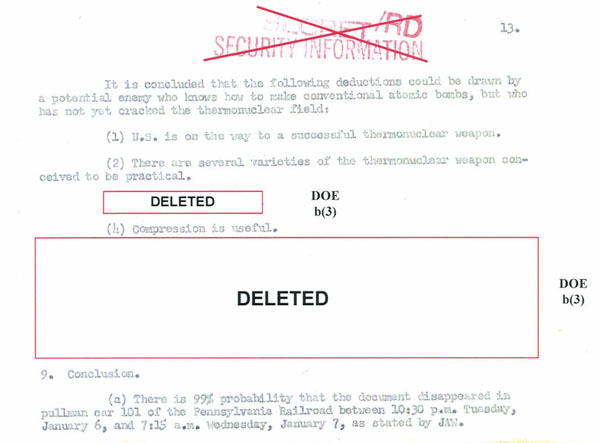

A redacted page from John Wheeler’s deposition to the FBI from March 1953 about his lost H-bomb document.

As you can see, this approach renders the background an impenetrable white, and allows the redactor to indicate the FOIA exemption under which they have declared the information unreleasable (in this case, DOE b(3) means the Department of Energy has determined that this falls under FOIA exemption b(3), which means that another law prohibits its release; in this case, probably the Atomic Energy Act of 1954).

In the past, the methods for redaction varied, including — my personal favorite — actually cutting out the offending material with a razor. I find the literalness of this approach quite appealing, especially since (as I describe in my book) the Latin root of the word “secrecy” is a word meaning “to cut.”

Figures for initiator production have been snipped out from this report of a 1947 meeting of the AEC’s General Advisory Committee.

But redaction is always fraught with problems, as I have written about before. Different redactors apply different judgment, even when looking at the same guidelines. A removal can actually draw attention to information, as opposed to hiding it, especially when multiple copies of the same document are available to compare. And so on.

But rarely does one find such impressive examples of “redaction gone wrong” as in a 1999 report by Los Alamos National Laboratory about the future of the US nuclear weapons stockpile. 1 The report is part of Martin Pfeiffer’s excellent archive of documents, many of which are re-scans of materials released by the National Nuclear Security Administration decades ago but whose online copies got corrupted years ago by sloppy data practices. 2

In this particular report there are lots of redactions that were made by simply putting a piece of white paper over the censored information and photocopying it. This isn’t a terrible way to redact… if the photocopier’s contrast settings are high enough that none of the censored information won’t be copied through the paper. But as you can see, even from a casual glance, this was not the case:

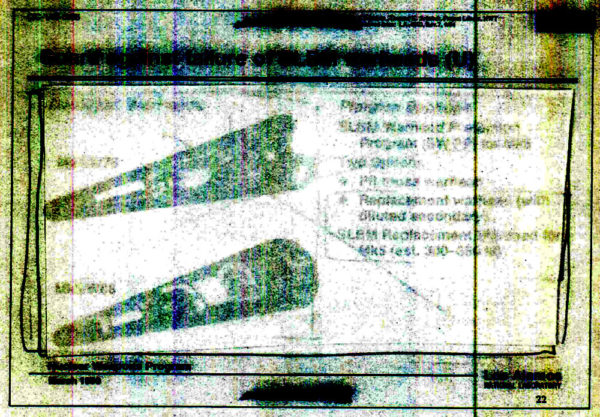

My attention was drawn to this by someone on Reddit, who showed that it only takes a little manipulation of the contrast slider in photo editing software to suddenly show something that probably wasn’t meant to be shown:

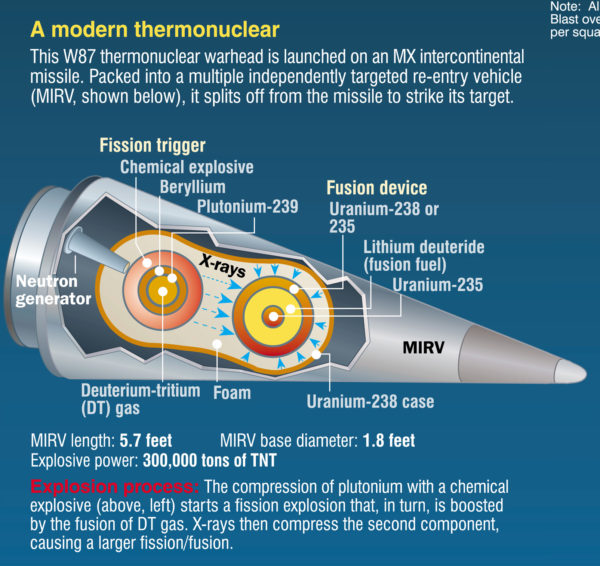

Oops. There are other examples in the same file, but this is the major one — not only can one read much of the redacted text, but we’re given a rare glimpse inside of modern thermonuclear warheads. Now, there isn’t a whole lot of information that one can make out from these images. The main bit of “data” are the roughly “peanut-shaped” warheads, which goes along with what has been discussed in the open literature for decades about how these sorts of highly-efficient warheads are designed. But the Department of Energy doesn’t like to confirm such accounts, and certainly has never before let us glimpse anything quite as provocative about these warheads. The traditional bomb silhouettes for these warheads are just the dunce-cap re-entry vehicles, not the warheads inside of them.

Does this mistake cause harm, all these decades later? It’s hard to see how. The fact that these cases are shaped like this is not news; that these warheads had “peanut-shaped” cases has been known publicly since around the time of this document’s creation, and was part of the coverage of both the Wen Ho Lee trial and the allegations of Chinese espionage at Los Alamos in the 1998 Cox Report. Even if one could get a better sense of the above than the blurry, seen-through-tracing-paper version of the above, it isn’t likely that just such an external view of a warhead casing would be that useful, by itself, to an enemy power. (North Korea has developed its own “peanut” shaped thermonuclear design, and showed off its casing to the world already.) The difficulty in making such a weapon is not in knowing it can be vaguely peanut shaped, in other words. This kind of thing just isn’t “secret” anymore, in the sense of unknown. But it is still “classified,” in the sense that it wasn’t meant to be legally released.

Traditionally, these kinds of screw-ups are used by critics of secrecy and the nuclear weapons establishment to indicate what a joke the whole thing is. I don’t go quite that far — as I’ve said in the past many times, in any system where you have millions of pages of material being reviewed by dozens (if not hundreds) of different human beings, you’re bound to have a few mistakes. Some are going to be larger than others. It’s an inevitability.

A speculative image of the internal components of a W87 nuclear warhead, originally from US News & World Report, reprinted in the Cox Report (1999).

It’s also just not clear that these kinds of mistakes “matter,” in the sense of actually increasing the danger in the world, or to the United States. I’ve never come across a case where some kind of slip-up like this actually helped an aspiring nuclear weapons state, or helped our already-advanced adversaries. That’s just not how it works: there’s a lot more work that has to be done to make a working nuke than you can get out of a slip-up like this, and when it comes to getting secret information, the Russians and Chinese have already shown that even the “best” systems can be penetrated by various kinds of espionage. It’s not that secrets aren’t important — they can be — but they aren’t usually what makes the real-world differences, in the end. And these kinds of slip-ups are, perhaps fortunately, not releasing “secrets” that seem to matter that much.

If anything, that’s the real critique of it: not that these mistakes happen. Mistakes will always happen in any sufficiently large system like this. It’s that there isn’t any evidence these mistakes have caused real harm. And if that’s the case… what’s the point of all of this secrecy, then?

The most likely danger from this kind of screw up is not that enemy powers will learn new ways to make H-bombs. Rather, it’s that Congressmen looking to score political points can point to this sort of thing as an evidence of lax security. The consequences of such accusations can be much more damaging and long-lasting, creating a conservatism towards secrecy that restricts access to knowledge that might actually be important or useful to know.

(For more on these kinds of political effects, check out my new book, which discusses these kinds of dynamics in some detail! This final message brought to you by my publisher…)

- Military Applications Group, “The US Nuclear Stockpile: Looking Ahead,” Los Alamos National Laboratory (March 1999). [↩]

- See this footnote for a previous discussion of the corruption issue. I have never found a way to fix these files and am very grateful to Marty for taking the same to re-scan them all from hard copies.[↩]

Wish there was a mistake like this regarding the DPRK HS-13 and HS-14 warheads. It would help for the reconstruction of both for the housing.

The headline “Guard against failure of SLBM warheads” has a “(U)” behind it. I suppose this means “unclassified”. Does this relate to the headline only, or to all information in that chapter/part?

Yeah, that just means the title of the report is unclassified (not all report titles are).