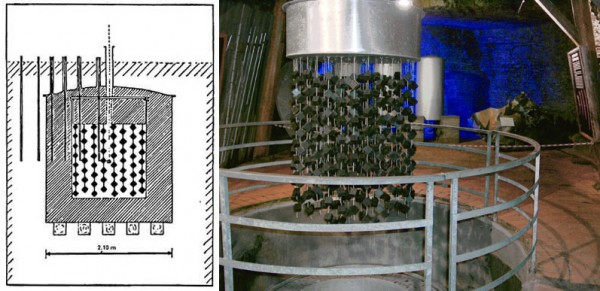

Diagram (left) and replica (right) of the Haigerloch heavy-water moderated reactor that Heisenberg and his team were trying to complete by the end of the war. The cubes are of unenriched uranium metal. Source: The diagram is from Walker’s German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-1949, the replica photo is from Wikipedia.

But eventually we came to find that the German atomic bomb project was stillborn. The Germans had a modest atomic power project, researching nuclear reactors, but were in no great rush for an atomic bomb. Of course, they are not necessarily unrelated projects — you can use nuclear reactors to produce plutonium. But it would require a much greater effort to do so than the Germans were engaged in. By any metric, the Germans were involved in a research program, not a production program. Their work was relatively small-scale, not a crash effort to get weaponized results.1

When did Manhattan Project officials know that the German program was not a serious threat, though? That is, when did they know that there was virtually no likelihood that the Germans would develop an atomic bomb in time for use in World War II? This is a question I get a lot, and a question that comes up in this season of Manhattan as well. It’s an important and interesting question, because it marks, in part, the transition from the Anglo-American bomb project from being an originally defensive project (making an atomic bomb as a deterrent against a German bomb) to an offensive one (making a bomb as a first-strike weapon against another non-nuclear country, Japan).

What makes this a tricky question to answer is that the word “know” is more problematic than it might at first seem. Historians of science in particular, because we are historians of knowledge, are quite aware of the ways in which “knowing” is less of a binary state than it might at first appear. That is, we are ordinarily accustomed to talk about “knowing” as if it were a simple case of yes or no — “they knew it or they didn’t.” But knowledge often is more murky than that, a gradient of possibilities. One might have suspicions, but not be sure. The amount of uncertainty can vary in all knowledge, and sometimes be deliberately encouraged or exaggerated to create a space for action or inaction. One’s knowledge can be incomplete or partially incorrect. And there are many different “levels” of knowledge — one might “know” that the Germans were working on reactors, but not know to what ends they were intending to use them.

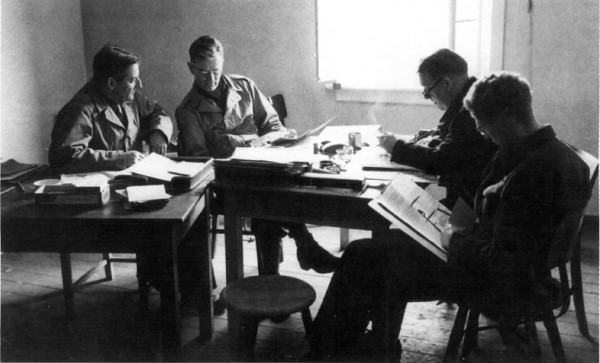

Allied troops disassembling the German experimental research reactor at Haigerloch, as part of the Alsos mission. Source: Wikipedia.

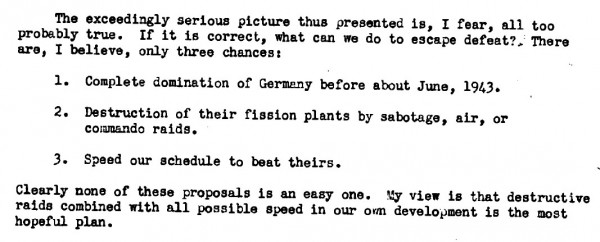

At one end of the “knowledge” question, we can point to the success of the Alsos mission. Alsos (Greek for “Groves”) was an effort in which Allied scientific and intelligence officers moved into German sites along with the invading troops, seizing materials, facilities, and even scientists (the latter being eventually detained at Farm Hall). By November 1944, Samuel Goudsmit, the scientific leader of the Alsos mission, had concluded that the German program appeared stillborn. By the spring of 1945, of course, they had made sufficient progress into Germany to know for sure. So that is a definite back-end on when they “knew” that the Germans had no bomb.2

But what did they know before that? At what point did the Germans stop being the fear that they had once been? This is the far more interesting, trickier question.

Among the American scientists, the fears of a German bomb peaked sometime in mid-1942. This, not coincidentally, is exactly when the Americans decided to accelerate their program from the research phase into the production phase: when their work changed from thinking about whether atomic bombs were possible to actually trying to build them. As the Americans became more convinced that atomic bombs were feasible to build in the short-term, they became more worried that the Germans were actually building them, and might have started building them earlier than the Americans. Arthur Compton, Nobel Prize winning physicist and head of the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory, wrote several particularly impassioned memos in the summer of 1942, urging an acceleration of atomic work largely out of fears of a German bomb:

“We have recently become aware that the threat of German fission bombs is even more imminent than we supposed… If the Germans know what we know — and we dare not discount their knowledge — they should be dropping fission bombs on us in 1943, a year before our bombs are planned to be ready.”3

Compton’s fears appear genuine, and rest on the conservative assumption that the Germans were just as smart, and just as aware of the possibilities, as the Americans. (And we know that they were, in fact, aware of all of these possibilities at the exact same time — but the Germans judged the effort more difficult, and more risky, than the Americans did.) There is no other basis for Compton’s assumptions, as he had no access to intelligence information on German efforts (and, indeed, his memo calls for more work in that field). But they were also self-serving, because they encouraged more effort towards his own goal, which was to accelerate the American bomb program. Compton was not at all alone in these fears; Harold Urey, James Conant, and Ernest Lawrence were all quick to point out that the American effort had been relatively slow to start, and that the Germans had clever scientists who ought not be underestimated.

Up until 1942, these fears were not, arguably, unwarranted. The Germans and the Americans were in similar positions. But, in a touch of irony, at the moment the Americans decided to switch towards developing a workable bomb, the Germans instead were deciding that they no longer needed to prioritize the program. They had concluded it would be an immense effort that they could ill afford to undertake, and that it was extremely unlikely that the Americans (or anyone else) would find success in that field.

So when did the picture change with regards to US knowledge, and who was told? Over the course of 1943 and 1944, more and more intelligence was gathered that, added up, began to suggest that the Germans did not have much of a project. In late 1943, General Leslie Groves appointed a specific intelligence group to try and suss out information about the enemy’s work. One of their avenues of approach was better collaboration with the intelligence services of the United Kingdom, who had far better networks both in Germany and in neutral countries than did the Americans. They even had a spy within Germany, the Austrian chemist Paul Rosbaud, who worked at Springer-Verlag, the scientific publisher. By the end of 1943, the British had concluded that the German program was not going anywhere. They were able to account for Heisenberg’s movements all too easily, and there seemed to be no efforts to industrialize the work on the scale necessary to produce concrete results in the timescale of the war. This information was duly passed on to the Manhattan Project intelligence services.4

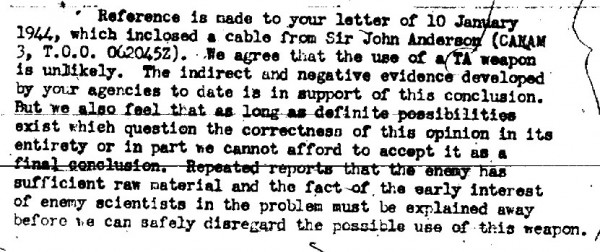

Did it have any effect? Not immediately. The Americans were not entirely sure whether the British assessments were accurate. As Groves put it in a memo to Field Marshall John Dill in early 1944:

We agree that the use of a TA [“Tubealloys” = atomic] weapon is unlikely. The indirect and negative evidence developed by your agencies to date is in support of this conclusion. But we also feel that as long as definite possibilities exist which question the correctness of this opinion in its entirety or in part we cannot afford to accept it as a final conclusion. Repeated reports that the enemy has sufficient raw material and the fact of the early interest of enemy scientists in the problem must be explained away before we can safely disregard the possible use of this weapon.5

Groves was being conservative about the intelligence — none of it definitely proved that the Germans weren’t working on a bomb, they just were reporting that they couldn’t see a bomb project. This is a common bind for interpreting foreign intelligence: just because you don’t see something, doesn’t mean it isn’t there (you may have missed it), but on the other hand, proving a negative can be impossible. (This problem, as I am sure the reader appreciates, still exists with regards to alleged WMD programs today.) In Groves’ mind, until there was really zero basis for doubt, they had to proceed as if the Germans were building a bomb.

But over the course of 1944, there are many accounts which indicate that the Americans at the top of the project, at least, were fearing a German bomb less and less. When Secretary of War Henry Stimson briefed several select Congressmen on the bomb work in February 1944, he had emphasized that “we are probably in a race with the enemy.” By contrast, when he briefed some of the same Congressmen that June, Stimson told them that “in the early part of this effort we had been in a serious race with Germany, and that we felt that at the beginning they were probably ahead of us.” Note the past tense — at this point, they were using the fears of the German bomb project to justify their earlier efforts, not their current ones. Vannevar Bush, who was at the meeting, emphasized in his notes that he told the Congressmen a bit more about “what we know and do not know about German developments,” but concluded with the thought that since the Allies began the heavy bombing of German industrial sites, the odds were that the Americans were “probably now well ahead of them.”6

Finally, in late November 1944, Samuel Goudsmit, head of the Alsos project, concluded that after inspecting documents, laboratory facilities, interviewing scientists, and doing radiological surveys of river water, that “Germany had no atom bomb and was not likely to have one in a reasonable time.” This was reported back to Groves, who appears to have not been entirely convinced until the total confiscation of German material and personnel was completed in the spring of 1945 and the end of the European phase of World War II. Even Goudsmit was unsure whether the conclusion was justified until they had confirmed it with further investigations.7

By the end of 1944, even the scientists at Los Alamos seem to have realized that Germany was no longer going to be the target. Joseph Rotblat, a Polish physicist in the British delegation to the laboratory, was the only one who left, later saying that “the whole purpose of my being in Los Alamos ceased to be” once it was clear the Allies weren’t really in a “race” with the Nazis.8

Several members of the Alsos mission, with Samuel Goudsmit, the scientific director, at far left. Source: Wikipedia.

So, in a sense, the final confirmation — the absolute confirmation — that the Germany didn’t have an atomic bomb only came when the Germans had totally surrendered. By late 1944, however, it had become clear that their bomb project was, as Goudsmit put it, “small-time stuff.” By mid-1944, the top American civilian official (Stimson) was already minimizing the possibility of German competition. By the end of 1943, British intelligence had concluded the German program was probably not a serious one. We have here a sliding scale of “knowledge,” with gradually increasing confidence, with no clear point, except arguably the “final” one, to say that the Allies “knew” that they were not in a race with the Germans. For someone like Groves, it was convenient to point to the uncertainty of the intelligence assessments, because the possibility of a German bomb, even one very late in the war, was so unacceptable that it could be used to justify nearly anything.

How much does it matter? Well, it does complicate the moral or ethical questions about the bomb project. If you are making an atomic bomb to stop Hitler, well, who could argue with that? But if you are making a bomb to use it against a non-nuclear power, to use it as a military weapon and not a deterrent, then things start to get problematic, as several scientists working on the project emphasized. Even Vannevar Bush, who supported using the bomb on Japan, emphasized this to Roosevelt in 1943, telling the President that “our point of view or our emphasis on the program would shift if we had in mind use against Japan as compared with use against Germany.”9

The degree to which the goals of the atomic bomb program shifted — from building a deterrent to building a first-strike weapon — is something often lost in many historical descriptions of the work. It makes the early enthusiasm and later opposition of some of the scientists (such as Leo Szilard) seem like a change of heart, when in reality it was the goals of the project that had shifted. It is, in part, a narrative about the shifting of perspective from Germany to Japan. Like the Allied knowledge of the German program, it was not an abrupt shift, but a gradual one.

- The best source for what the Germans were actually doing is still Mark Walker, German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), and Mark Walker, Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, And The German Atomic Bomb (New York: Plenum Press, 1995). [↩]

- Of course, this assumes Alsos got everything right, and it is not entirely clear that they did. There are still several interesting historical questions to be answered about the German program. As I’ve written elsewhere, I don’t think Rainer Karlsch’s work on the German atomic program is compelling in its final thesis, but many of the documents he has found do point towards the Alsos mission having some limitations in what it was able to find and recover, and towards further work to be done in fully understanding the German program. [↩]

- Arthur Compton to Vannevar Bush (22 June 1942), copy in Bush-Conant File Relating the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1940-1945, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, RG 227, microfilm publication M1392, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., n.d. (ca. 1990), Roll 7, Target 10, Folder 75, “Espionage.” Compton refers to “copper,” which was then the American code-name for plutonium, and “magnesium,” a code-name for enriched uranium. [↩]

- The best overall source on US efforts to get information about the German bomb program, and the source of much of this paragraph’s information, Jeffrey Richelson, Spying on the Bomb: American Nuclear Intelligence from Nazi Germany to Iran and North Korea (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), chapter 1. [↩]

- Leslie R. Groves to John Dill (17 January 1944), copy in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 5, Target 8, Folder 18, “Radiological Defense.” [↩]

- Vannevar Bush to H.H. Bundy (24 February 1944), and memo by Vannevar Bush on meeting with Congressmen (10 June 1944), copies in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 2, Target 8, Folder 14, “Budget and Fiscal.” [↩]

- Samuel Goudsmit, Alsos (New York: H. Schuman, 1947), on 71; see also Richelson, Spying on the Bomb, chapter 1. [↩]

- Joseph Rotblat, “Leaving the bomb project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (August 1985), 16-19, on 18. See also my post discussing some of the alternative/contributing factors regarding Rotblat’s leaving the project, as discussed by Andrew Brown in his book, The Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience: The Life and Work of Joseph Rotblat (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). [↩]

- Vannevar Bush, “Memorandum of Conference with the President” (June 24, 1943), copy in Bush-Conant File Relating the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1940-1945, Records of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, RG 227, microfilm publication M1392, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., n.d. (ca. 1990), Roll 2, Target 5, Folder 10, “S-1 British Relations Prior to the Interim Committee No. 2.” [↩]

Alex: I remember Philip Morrison’s describing Gen. Groves’ summoning him to Washington from Los Alamos and installing him in a small office next to his own. There, Phil analyzed effluent from the waterways near the putative German site and was able to conclude that there was no Nazi bomb project.

Hello Priscilla! Yes, Morrison’s was one of the many angles they pursued. Ultimately, though, until Germany was fully defeated, there was enough uncertainty in the equation for Groves to hold out the possibility of a German bomb. Although after awhile, especially seeing how large and detectable the American program had become, one has to start imagining the Germans capable of performing miracles to see them actually developing such weapons in time for the war.

Alex, just an outstanding article that is making me do a lot of thinking. I love it when that happens! Your last paragraphs are gems and, to me, very provocative. I think that if the bomb had been ready in 1944 or early 1945 the Allies would have used it on Germany; even with the uncertainty of the existence of a German bomb program. I really do not think it would have been merely a deterrent weapon. Allied leadership had a total war mindset and I think the thought of not using a weapon is something they could not fathom even with the risk of German retaliation. Of course Churchill would have been in on the decision with either Roosevelt or Truman and they had demonstrated a lot of risk taking every step of the way in that terrible war.

Did the intelligence people take into consideration how the German’s might have delivered an atomic bomb?

Was Moe Berg’s mission to sit in on Heisenberg’s lecture in Zurich late in 1944 important in determining German progress? It is almost never mentioned when this subject is examined.

We have very few sources on what Roosevelt would have thought about using a bomb on Germany, but there are some indications that if he had an atomic bomb in early 1945, he might have used one on them. It would have provided some logistical difficulties (notably, there were no B-29s in the European theatre), but not insurmountable ones, if the bombs had themselves been ready.

I haven’t seen discussions of delivery but they were as worried about them being used on London (a much easier delivery target than, say, New York) than the continental United States.

The Berg mission is a very interesting, somewhat anomalous event. Its somewhat ad hoc nature — one man with a gun, going with his gut impression — somewhat leads towards that, and the desperate possibility that the Germans might have stumbled across an easier way to make the bomb. But the fact that Berg didn’t think Heisenberg was doing anything of course would not have, alone, satisfied the uncertainty for someone like Groves.

Sure London would be considered a possible target, and God knows Hitler wanted to make London suffer, but the Germans had nothing that could deliver a weapon the size and weight of an atomic bomb, didn’t realistically even try. Maybe by ship but that would have been a very desperate method with a very large possibility of failure. Zeppelin would have also had a high possibility of failure and certain death for the pilots. Could a Zeppelin lift a WWII era atomic bomb?

Maybe Paris. Hitler did order its destruction. Could have put it up on the Eifel Tower.

Moving a few B-29s to England would not have been a problem and the US would never have delivered the bomb in a British plane. Hell, we moved several to China without any real problems. It was keeping them supplied and safe that was the issue.

Heisenberg was considered by many as the only German scientist left in Germany capable of leading a possible bomb project. He was the focus of a lot of attention by the intelligence community and part of a very interesting part of the post hostilities investigation into a possible German bomb project. Farm Hall coupled with the Berg mission makes for a very fascinating story.

Thanks for linking to the Rhodes article in your Tweet. Two outstanding articles to get my little gray cells sparking on a Friday afternoon. Thanks again!

I don’t know if delivering something that heavy a relatively short distance wouldn’t have been impossibly hard, but I’m not a plane guy. I suspect a bomb the dimensions and weight of Little Boy could have been made to work; it’s heavy, to be sure, but the dimensions are otherwise not too taxing. Fat Man was taxing even for a B-29, a very snug fit. But this is just a rough hunch. If the Germans had developed a bomb, they could have probably developed a delivery vehicle for the European theatre (doing something intercontinental would have been much more difficult).

I just keep thinking about how Hitler began to mobilize for war in 1935 but by 1940 was completely unprepared and unable to mount an invasion of Britain. The US mobilized for war in 1940 and by 1942 was completely prepared and successfully pulled off a major amphibious invasion.

Germany was only able to employ half as many planes for Barbarossa as he had for the invasion of France. Germany still depended heavily on horse to move artillery and supplies. Germany, in some instances, used bicycles to move troops.

Germany never developed a four engine bomber, much more precise than V-2 or V-1.

Hitler might have gotten the bomb and never have come up with a way to get it to any strategically important target.

The German Junkers 390 aircraft could probably have carried a Little Boy type weapon from France to Britain. Fat Man might not fit. 10000 pounds for 250 miles shouldn’t be a problem for an aircraft that made a trip from France to New York City and back.

We would have had to accelerate the Silverplate B-29 program to be able to deliver an atomic bomb in late 1944.

The Allies did not need a B-29 to carry an atomic bomb; if it had been available in 1943, they could have used the Avro Lancaster, which had a sufficiently large bomb bay.

At the time, the biggest battle front was the Soviet Union. What was in the Soviet Union, during WW II, that would have been a likely target?

The Soviet Union would have presented a lot of appealing targets for the Germans, either in terms of symbolic significances (Moscow, Leningrad) or industrial significance (if they could get a bomb over the Urals). But I’ve never seen anything that suggested the Germans were really thinking along these lines; even the US administrators didn’t seriously hammer out their targeting criteria until fairly late in the game (early 1945).

I think at least in the early days of the war, it was reasonable for the Allies to think that if an atomic bomb was possible, probably the Germans were working on it already. After all the Germans were the first to field jet airplanes and ballistic missiles – neither one in numbers that made much difference, but typically their military technology was at least as advanced as the Allies’ and frequently more advanced.

I have always felt that there was another factor driving the increasing disdain for the possibility of a Nazi bomb: the size and scale of the Manhattan project making clear just how much effort it would take to build an atomic bomb. If your cost estimate for a nuclear weapon is MAUD the idea of a Nazi Bomb is terrifying. If your cost estimate is the actual Manhattan Project, the idea of a Nazi Bomb is amusing. As the Manhattan Engineering District grew more and more expensive, the idea that the Nazis could match this receded as a threat. (The MAUD estimate for the total cost of a Bomb wouldn’t cover the cost of K-25 alone, leave alone Y-12, S-50, X-10, etc.)

I agree — as the US program progressed, it became increasingly clear what the size of the effort was, and how incompatible that was going to be with the Germans’ situation (and how unlikely it was going to be to “miss” it). Oppenheimer, however, always held out the possibility that the Germans might find a way to enrich uranium “in a kitchen sink” — the science was still quite new. (And indeed, there are different ways to do it that the Americans never figured out how to manage during the war, like the gas centrifuge approach.) Which is just to say, when one is searching for sources of uncertainty, one usually can find them.

you can use nuclear reactors to produce plutonium

Is there any indication of what the Germans knew about plutonium at the time?

Yes, they definitely knew that it ought to exist and that if you had a reactor you ought to be able to produce it. (They referred to it as “94,” of course, and not “plutonium.”) They also knew it ought to be fissile. But I’ve never seen any evidence that they were able to produce any (they lacked cyclotrons, which is how Seaborg et al. produced the first samples), or that it got beyond the theoretical stage.

But the Germans did have access to Joliot-Curie’s cyclotron in Paris. While the Germans knew about plutonium, the Allies did not know that the Germans knew until quite late.

Were there ever fears of a Japanese nuclear program?

There don’t seem to have been many serious concerns about one. They were curious (at the end of the war) about any research they had done, but they do not seem to have been afraid of them getting a bomb in time for use during the war.

The Japanese nuclear program is interesting. I have not seen much it at al. Some (can’t remember who) claimed that it was quite advanced at the end of WWII. And they had a cyclotron at the university of Tokyo (if I remember correct). It is interesting to know why this was not conceived as a threat. There must have been some reasons for this.

There are a few who state it was advanced, but the evidence is lacking. They had a program that was largely about research and investigating (on a very small scale) the sorts of ways in which fission technology might be realized. There is no evidence that they had anything of the industrial size necessary to actually produce concrete results, and those who claim that they might have had a bigger program like to just gesture to the idea that somehow it might have all been hidden away in Korea without leaving any kind of record in the mainland. I don’t find it very credible. The fact that the people who like to talk about a Japanese program generally have an obvious political agenda (i.e., if the Japanese were working on a bomb — or near to one — then it would justify our using the bomb on them) makes it even less credible in my eyes.

The Americans generally did not think the Japanese had the technical infrastructure necessary to produce something like a bomb, or known access to the kinds of raw materials (like uranium) you would require to do so (whereas the Germans were in possession of the mines of Czechoslovakia, a known uranium source before the war). One can take issue with this assessment (the Japanese did have some top-notch physicists, and the US also underestimated the Russians in the postwar). But again, nothing credible (just orally-transmitted rumors) has ever indicated they had more than an exploratory program. And the exploratory work is pretty well-documented, as is their decision not to accelerate to anything larger.

Regarding who knew what about who was doing research on the atomic bomb, there is an article in the journal Nitrocellulose Nov. 1940 by von Dr, Alfred Stettbacher that might be of interest. It is titled Der amerikanische Super-Sprengstoff “U-235”. Stettbacher talks about a bomb capable of destroying tanks and military bunkers. This article has been translated into Japanese, probably by Takeo Yasuda and appears in a review of the atomic bomb in the TONIZO documents April 1943.

I haven’t read the article in question, but I would note that in 1940, the US was not working on an atomic bomb program with any intensity. If there is any actual knowledge of US work reflected in such an article, it is likely based on published work before the curtain of secrecy came down. The US program did not accelerated until mid-1941 and was not really a dedicated bomb production program (the Manhattan Project) until late 1942.

Alex, Excellent points by you and respondents.

It’s been striking (even ironic) to realize that in our “race” for the A-bomb against the Germans how June 1942 was a significant cross-over point. That month Heisenberg told Speer they couldn’t produce a useful weapon before Germany would win the war, and they folded. The same month the US A-bomb project was finally turned over to the Army for an all-out effort.

It is one of these places in history where the decisions of a few people in a few rooms had very large ramifications going forward. In one room, a country decides to go all-out in making a bomb. In another room, thousands of miles away, a country decides that it isn’t worth the difficulty. The past is always a mix of macro- and micro-historical forces, but it’s those moments when they intersect in a moment — a decision — that I find most interesting.

Great piece Alex, raises questions I’m dealing with in a forthcoming book – Operation Big – to be published by Amberley Publishing in the UK next year.

Compton mentions in his letter at the end of the first par ‘the attached memo explains their (the Germans’) schedule’ – do you have that memo? And if so, could I see it?

Thanks again for a great piece.

COLIN BROWN

It is not clear. From the position in the file, it may be a memo written by Eugene Wigner, dated June 20, 1942. It is not included in the microfilm file that was declassified in the 1970s, though it may be in NARA in the original file. (Or it may require a FOIA request.) I don’t have a copy of it, I don’t think. But it may be something that was not attached in that instance of the letter (which was itself an attachment to a memo Vannevar Bush was sending to General Strong). Attachments to attachments to attachments…

[…] of whom trusted Oppenheimer. Pash would later be given the job of being the military head of the Alsos mission — to better to harass German atomic scientists rather than American […]

Would the allies have surrendered if Germany fielded an atomic bomb?

Was the expectation that Germany wouldn’t use the bomb if we had developed it first? A 1940s version of MAD?

Was the expectation when the Manhattan project was first undertaken that we would use the bomb only after the Nazis used it first?

What would ever have been the case that it would have been acceptable to use the atomic bomb against Germany considering that wherever it would have used would have resulted in tremendous civilian casualties somewhat similar to those in Japan?

The US scientists clearly thought that the Germans would use a bomb if they had it. Many of them originally thought the bomb they were developing was a deterrent against this possibility, and protested when they saw it was not going to be the case. See here and here for a few responses.

Would the Allies have surrendered? This gets into a speculative realm. I doubt it, personally. Even the conditions under which Japan surrendered were pretty specific (and may not have been attributable to the bomb alone) — the bomb, even in the “orthodox” interpretation of the Japanese surrender, is a “final straw” that allowed an already-defeated country a way out.

On the question of whether we would have used it on Germany, I have written a bit here.