The primary motivation of much Manhattan Project secrecy was to keep the Germans from finding out that the United States and United Kingdom were feverishly working on developing nuclear weapons. So it seems a pretty sensible question to ask: Did it work? That is, did the secrecy keep the Germans from knowing about Allied progress on the bomb?

Strangely enough, I wasn’t able to find much of anything published on the question of what knowledge, if any, the Axis powers had about the atomic bomb. The fact that they didn’t develop one themselves is not strong evidence — it just might mean that such knowledge was very limited, or not believed, or not shared correctly. I can’t do the topic the justice it deserves, because I’m not conversant enough with the sources of Axis foreign intelligence, but I can present some thoughts and intriguing little discoveries on here regarding the German program. If anyone has further thoughts, or evidence, I’m all ears.

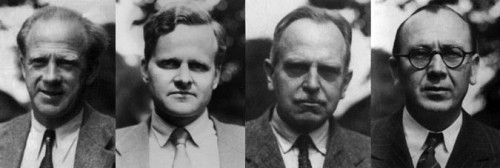

Where might we look for such evidence? The major, obvious source are the Farm Hall transcripts. Farm Hall was the British country manor where ten of Germany’s nuclear scientists were kept for six months. Their conversations were bugged. They were, on August 7th, told about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and the transcripts were carefully probed at the time, and many times since, for any insight given into what the German nuclear weapons program had been at the time. The transcripts are a notoriously tricky primary source, in part because the original German copies have apparently since been lost (so we only have an English translation), and because there are some indications that the scientists were aware they were being bugged. Separately there is the psychological complexity of the issue, as the scientists were trying to come to terms with themselves, an imagined German public, and an imagined world public regarding their participation (or lack thereof) in making nuclear weapons for Hitler.1

With that said, is there anything in the Farm Hall transcripts that enlightens us one way or the other? The most significant part is that the announcement of Hiroshima, first given orally, “was greeted with incredulity.” See, for example, this sort of exchange:

HEISENBERG: Did they use the word uranium in connection with this atomic bomb?

ALL: No.

HEISENBERG: Then it’s got nothing to do with atoms, but the equivalent of 20,000 tons of high explosive is terrific. […]

GERLACH: Would it be possible that they have got an engine [reactor] running fairly well, that they have had it long enough to separate “93”? [neptunium]

HAHN: I don’t believe it.

HEISENBERG: All I can suggest is that some dilettante in America who knows very little about it has bluffed them in saying: “If you drop this it has the equivalent of 20,000 tons of high explosive” and in reality doesn’t work at all. […]

WEIZSÄCKER: I don’t think it has anything to do with uranium. […]

HAHN: If they really have got it, they have been very clever in keeping it secret.2

All of which has been sometimes taken as pretty strong evidence that these guys didn’t know much about the Allied project. But a closer reading is less clear, because, among other things, not everyone is participating in this discussion. One of the many problems with the German nuclear program was a lack of coordination and a lack of shared knowledge. That Otto Hahn knew nothing of it seems entirely believable, but irrelevant, since he wasn’t really working on the nuclear program in any kind of military capacity. Werner Heisenberg and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker worked together so it makes sense that they would be on basically the same page. But what about the others?

Walter Gerlach was in a more administrative role, so one might imagine he would know of any foreign intelligence on the subject. He speaks very little in this part of the transcript, only the question about reactors, and he is not one of the outright initial doubters. Asking whether they could have had reactors does not indicate that he was unaware of an Allied bomb project in general, especially given the compartmentalization of the Manhattan Project. He does, much later in the transcript, apparently express private surprise with Heisenberg that “they had known nothing about the preparations that had been made in America,” though. And what of Kurt Diebner? Diebner ran the other major research wing of the German nuclear program, separate from Heisenberg. He says almost nothing in this section of the transcript, only noting that “there is also a photochemical process” for enriching uranium. Again, this tells us nothing about what he knew.3

Probing the transcript further, we find a few other odd exchanges:

HAHN: From the many scientific things which my two American collaborators sent me up to 1940, I could see that the Americans were interested in the business.

WEIZSÄCKER: In 1940 van der Grinten wrote me, saying he was separating isotopes with General Electric.

HARTECK: Was van der Grinten a good man?

WEIZSÄCKER: He wasn’t really very good but the fact that he was being used showed that they were working on it.4

I read these as Hahn and Weizsäcker trying to recall whether they had any indication of Allied interest. Considering their only memories are from 1940 (before the Manhattan Project really began), they are actually a good indication that they did not have any truly specific intelligence.

Heisenberg three times tells a story about being contacted from someone in the German Foreign Office about uranium questions:

HEISENBERG: About a year ago, I heard from Segner [probably Sethke] from the Foreign Office that the Americans had threatened to drop a uranium bomb on Dresden if we didn’t surrender soon. At the time I was asked whether I thought it possible, and, with complete conviction, I replied: “No.”5

Now that is a strange story. I have no idea what this Sethke would have been referring to — some strange rumor. Whether it is just nonsense, or based on some actual intelligence, it’s impossible to know from just this snippet. Later, when Heisenberg tells another version of the story (this time making his answer that it was “absolutely possible”), he specifies it was in July 1944 and that it was “a senior SS official” who had asked him about the bomb.6

There is also one small exchange before the German scientists were told about Hiroshima. On August 4th, Heisenberg, Gerlach, and Hahn had this exchange:

GERLACH: The [British] Major [Rittner] asked me what we had known about scientific work in enemy countries, especially on uranium. I said, “Absolutely nothing. All the information we got was absurd.”

HEISENBERG: In that respect one should never mention any names even if one knew of a German who had anything to do with it.

GERLACH: For instance, I never mentioned the name of that man Albers (?). The “Secret Service” people kept asking me: “From whom did you get information?” and I always replied: “There was an official in Speer’s ministry and in the Air Ministry who gave it out officially.” I did not say it was Albers (?) who did it.

HEISENBERG: I had a special man who sent me amazing information from Switzerland. That was some special office. Of course I have burnt all the correspondence and I have forgotten his name.

HAHN: Did you actually get any new information from him?

HEISENBERG: At that time I always knew exactly what was being discussed in the Scherrer Institute regarding uranium. Apparently he was often there when Scherrer lectured and knew what they were talking about. It was nothing very exciting but, for instance, he once reported that the Americans had just built a new heavy water plant and that sort of thing.7

And there it ends. Other than the mention of heavy water, it is too vague to make much sense of. (The Manhattan Project built several heavy water plants are part of what they called the P-9 Project, as part of their “leave no stone unturned” approach. They upgraded an existing ammonia plant at Trail, British Columbia to produce heavy water, and built three supplementary facilities at military sites in West Virginia, Indiana, and Alabama.)

After the scientists had heard the official BBC radio announcement, they all began to believe it was true, and worked out fairly quickly how it probably would have worked (though even there, they were still impressively confused at times) and famously hashed over why they didn’t get one made. No further invocations of foreign information or intelligence were made that I found.8

My overall impression is that for the bulk of the ten scientists, the Allied atomic bomb probably did come as a genuine surprise of immense magnitude. But there are enough hints there to suggest that various bits and pieces were out there amongst their foreign intelligence officials, whether they shared all of that with the scientists or not. And as we’ve see in the Soviet case, just because the spies know something doesn’t mean it percolates back to the scientists working on it — the use of foreign intelligence is not a straightforward operation. And there are several scientists whose reactions were not individually recorded (e.g. Diebner). Of the scientists who talked a lot, they seemed genuinely clueless about what the Americans had done, but not all of them talked.

Are there any other indications? One thing that one finds on the Internet are assertions that the last attempt by the Nazis to deposit saboteurs on American soil, Operation Elster (Magpie), was supposedly aimed at sabotaging the Manhattan Project. Like all such Nazi efforts, the saboteurs in question were rounded up pretty quickly. Were they really targeting the Manhattan Project? I suspect not. The sources that give such information all seem to trace back to a postwar memoir of one of those captured. David Kahn has written that he thinks it is nonsense; I am inclined to agree.9) The idea that a single pair of spies would be sent to gain information on, much less sabotage, the Manhattan Project is too silly to be believed without corroborating evidence.

J. Edgar Hoover, 1941. Source.

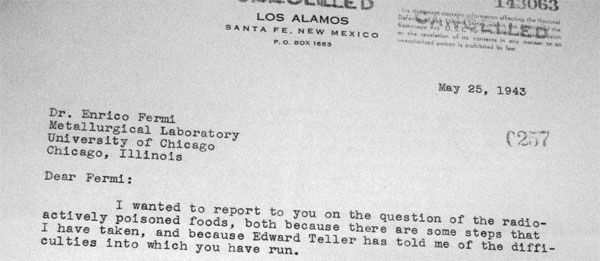

But there is one last interesting source that I stumbled across. In early February 1945, J. Edgar Hoover wrote a memo to Harry Hopkins (one of Roosevelt’s closest aides) explaining that the FBI had information that indicated German interest in atomic matters. Specifically, Hoover wrote:

As you are well aware, the Army for the past two years has been vitally interested in a highly secret project for the development of an atomic explosive. […]

Recently, in connection with the operation of a radio station by a German agent under control of the Federal Bureau of Investigation but which station the Germans believe to be a free station, an inquiry was received from Germany containing the following questions regarding the status of atomic explosive experimentation in the United States:

First, where is the heavy water being produced? In what quantities? What method? Who are users?

Second, in what Laboratories is work being carried on with large quantities of uranium? Did accidents happen there? What does protection against Neutronic Rays consist of in these laboratories? What is the material and the strength of coating?

Third, is anything known concerning the production of bodies or molecules out of metallic uranium rods, tubes, plates? Are these bodies provided with coverings for protection? Of what do these coverings consist?10

Now this looks like a legitimate technical intelligence inquiry. These are very specific questions regarding reactor construction. Not necessarily bomb construction, mind you. But it does look like someone working on reactors passed some questions up the chain of command. (The fact, incidentally, that this came to the FBI from a double-agent is also telling — the German foreign intelligence networks were notoriously compromised, yet another reason they missed so much.)

The questions reveal, though, that whomever asked them did not realize that the Americans had already been building massive, industrial-sized, carbon-moderated (not heavy water!) nuclear reactors in Hanford, Washington. Note the lack of any queries regarding uranium enrichment. Note that the questions are narrowly technical, the kind of questions you would ask if you are trying to build your own reactor, not ferret out a clandestine bomb program.

That the Germans were asking such basic, ignorant questions so late in the game — the Red Army was bearing down on Berlin and their atomic program, like so many other things, was in a tizzy11 — is perhaps the greatest indication that they knew very little about the American Manhattan Project indeed. That they were asking questions at all is not surprising, but the lateness perhaps is. The Soviet physicist Georgii Flerov figured out that the Americans must be working on a nuclear program in 1942, when he noticed that nobody was publishing on the subject — specifically, that nobody was citing his publication on the spontaneous fission of uranium-238. One wonders why the Germans were less observant of this fact, especially given the amount of “brain drain” their own institutes suffered.12 They also appear to have missed or misunderstood all of the various leaks, accidental disclosures, and other signs that drove General Groves and others involved with Manhattan Project security so mad. Many pieces were there for them to put together, but they didn’t solve the puzzle.13

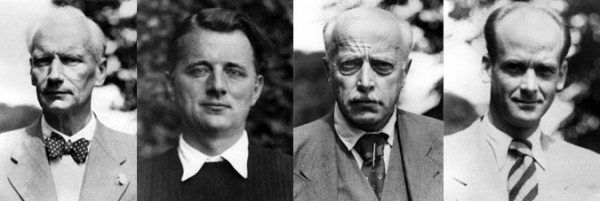

Allied troops disassembling the German experimental research reactor at Haigerloch as part of Alsos.

Lastly, we have the take of Samuel Goudsmit, the head of the Alsos expedition. In an unpublished memorandum written in late 1945, claimed that the Alsos investigation into the German work had shown that “the enemy was equally ignorant of Allied scientific and technical work,” though notes that in 1939, a team of three Germans were sent to the USA to learn about American interest in uranium research. (This was well before there was much American interest in such.) As he was prone to do, Goudsmit generalized greatly from this, assuming that scientific and technical intelligence was too difficult to pick up during that war. The Soviets, as always, proved an important exception to Goudsmit’s generalizations.14 In any case, though, this does indicate that there aren’t probably an exciting espionage gems hiding in the Alsos records.

Wrapping everything up, my basic conclusion is that if German intelligence had an inkling about the American atomic bomb program, they didn’t develop the idea and they didn’t communicate it to several of their top scientists on the program. Heisenberg seems genuinely foolish on the entire subject. Diebner’s lack of participation makes it hard to gauge his knowledge, but it strikes me as strange (though not impossible) that he would know of such things but Heisenberg would be ignorant of them. Entirely separate is the question of who asked the SS to investigate what the Americans were doing with heavy water — but the queries there demonstrate that whomever is asking knows almost nothing about the Allied program, and may in fact be trying to find out how to improve their own reactor work.

A consistent theme in the Farm Hall transcripts and the Alsos investigation is that the Germans seem to have honestly thought that their work on the “uranium problem” was well beyond what anyone else might have been doing, and that the Allies would be desperate to “buy” their reactor research in the postwar. They apparently were not motivated to check to see whether this arrogance was founded, and part of the depression and desperation one sees them going through after Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a remark on their perception of irrelevance. As Otto Hahn chided them right after they learned of Hiroshima: “If the Americans have a uranium bomb then you’re all second raters.”

- The best copy of the transcripts is Jeremy Bernstein’s heavily annotated version, Hitler’s Uranium Club: The Secret Recordings at Farm Hall, Second Edition (New York: Copernicus Books, 2001). My quotations and citations refer to this specific version. [↩]

- Bernstein, 116-117. [↩]

- Photochemical processes for enriching uranium were investigated during the Manhattan Project, but not seriously pursued. [↩]

- Bernstein, 119. [↩]

- Bernstein, 124. [↩]

- Bernstein, 139. [↩]

- Bernstein, 108. Note that the (?)’s are in the original transcript. [↩]

- There is one small bit about talking about thorium with an (Indian) Japanese spy, but it seems unrelated to the bomb question directly, and the spy in question doesn’t seem to have known anything. [↩]

- David Kahn writes in Hitler’s Spies: German Military Intelligence in World War II, “[Erich] Gimpel’s [one of the spies] ghostwritten book, Spy for Germany, must be used with the greatest caution, as it differs in a number of critical points from his statement [to the FBI]. The most important are the book’s claims that he was assigned to ferret out atomic secrets, that he succeeded to some extent, and that he radioed a message to Germany. None of these are supported by his statement or by Colepaugh’s [a collaborator] or by postwar interrogations of his spymasters, and the atomic claim is specifically contradicted by a statement of Schellenberg’s [a top Nazi spy].” There just doesn’t seem to be any hard evidence behind the assertion that Elster had something to do with the Manhattan Project. Gimpel’s books provide zero believable details about the matter — he reports that he was just supposed to figure out what was going on (no list of targets, names, theories, etc. [↩]

- J. Edgar Hoover to Harry Hopkins (9 February 1945), in Harrison-Bundy Files Relating to the Development of the Atomic Bomb, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1108 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Folder 62: “Security (Manhattan Project),” Roll 4, Target 8. [↩]

- See Samuel Goudsmit, Alsos (Tomash, 1983 [1946]), 183-185. [↩]

- At one point in the Farm Hall transcripts, it is noted that “Hahn remarked on the fact that there had been no publication of work on uranium fission in British or American scientific journals since January 1940, but he thought there had been one published in Russia on the spontaneous fission of uranium with deuterons.” So, at least retrospectively, Hahn realizes that there was this silence, with the exception of Flerov (probably the Russian he is thinking about). [↩]

- Goudsmit describes a conversation between Paul Rosbaud and Walther Gerlach in February 1945 in which Rosbaud asks Gerlach, “Have you considered that the American, British, or Russian scientists know as much or perhaps more about it than you do?” If this actually occurred, one wonders if Gerlach didn’t follow up on the issue, ergo the spy query. But this is just supposition. On the conversation, see Goudsmit, Alsos, 185. In any case, the whole conversation, if true, is further evidence of Gerlach’s ignorance at that point — he was still under the delusion that the Allies would have something to gain from the German work on heavy water. [↩]

- Samuel Goudsmit to C.P. Nichols, “Scientific Intelligence” (26 November 1945), Goudsmit papers. [↩]