Some time ago, I wrote a blog post about a hypothesis I had regarding President Truman and the decision to use the atomic bomb. My basic thesis then (and continues to be) is that there is good reason to think that Truman did not understand that Hiroshima was a city with a military base in it, and not merely some kind of military installation. Truman’s confusion on this issue, I argue, came out of his discussions with Secretary of War Henry Stimson about the relative merits of Kyoto versus Hiroshima as a target: Stimson emphasized the civilian nature of Kyoto and paired it against the military-status of Hiroshima, and Truman read more into the contrast than was actually true.

I have kept poking around this issue for some time now, and written an article-length version of it (more on that in due time). I feel even more confident in it than before, having gone over the relevant documents very closely and talked about with many scholars (including at a conference in Hiroshima last summer), though there are some aspects of the original blog post that I would refine or revise.

But I thought I’d share one set of documents that I found extremely illuminating and interesting, and useful for thinking about how the “narrative” of Hiroshima changed over a very short period of time in August 1945. I have not seen any reference to these in the work of any other historians, not because they are slouches (they are not), but because you have to be asking very specific questions to think they are a possible source of the answers.

The press release sent out under Truman’s name after the bombing of Hiroshima was not written by him. It was largely written by Arthur Page, a Vice President at AT&T and the “father of modern corporate public relations,” at the request of the Interim Committee of the Manhattan Project. Page was an old friend of Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War, and Stimson wanted the first statement to be a very carefully-written document, as it was meant to credibly describe a new weapon and outline possible paths forward for the Japanese. Truman was shown the final version of it, but he didn’t add or remove anything from it. It is interesting (for my purposes) to note that if you did not know whether Hiroshima was a city or an isolated military base, the initial announcement would not clarify that for you, even if you were (like Truman) the one reading it aloud.

A far more interesting case is the second speech that Truman gave which mentioned the atomic bomb. This was a radio address given on the evening of August 9, 1945, not long after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. The atomic bomb only occupies a small part of the overall speech — it is really a speech about what had happened at the Potsdam Conference the weeks previous. But the parts on the atomic bomb are fascinating to read. Here are the parts I’d like to draw your attention to in particular:

The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians. But that attack is only a warning of things to come. If Japan does not surrender, bombs will have to be dropped on her war industries and, unfortunately, thousands of civilian lives will be lost. I urge Japanese civilians to leave industrial cities immediately, and save themselves from destruction. […]

Having found the bomb we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare. We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans.

Two things interest me about the above. One is that the first paragraph emphasizes that Hiroshima was a “military base,” and that they wanted to avoid, “insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.” Now, Hiroshima was not, strictly speaking, a military base — it was a major city that contained a military base. There is a difference there, and fewer than 10% of the casualties were military. The paragraph further warns that bombing cities might occur — it doesn’t ‘fess up to having already done it, but puts it as a thing for the future.

The second paragraph quoted does something a bit different: it justifies the bombing, first by saying that the Japanese were awful and deserved it, then by saying that the use of the bomb was really a humane act, and using it would “shorten the agony of war,” and would save American lives.

We will come back to both of these in a minute. Let’s instead ask: who wrote this speech? Given the background of the first press release, one might be surprised to find that the answer is… Harry Truman. Well, he wrote the first draft. As he wrote in a note on August 10th:

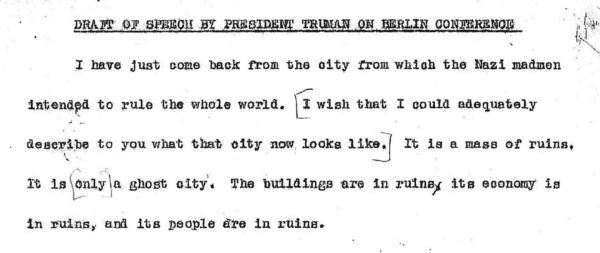

“While all this has been going on, I’ve been trying to get ready a radio address to the nation on the Berlin conference. Made the first draft on the ship coming back. Discussed it with [James] Byrnes, [Samuel] Rosenman, Ben Cohen, [William] Leahy and Charlie Ross. Rewrote it four times and then the Japs offered to surrender and it had to be done again.”

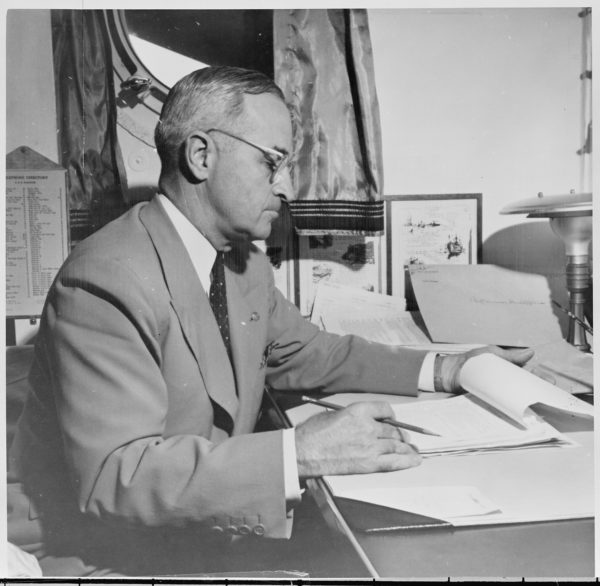

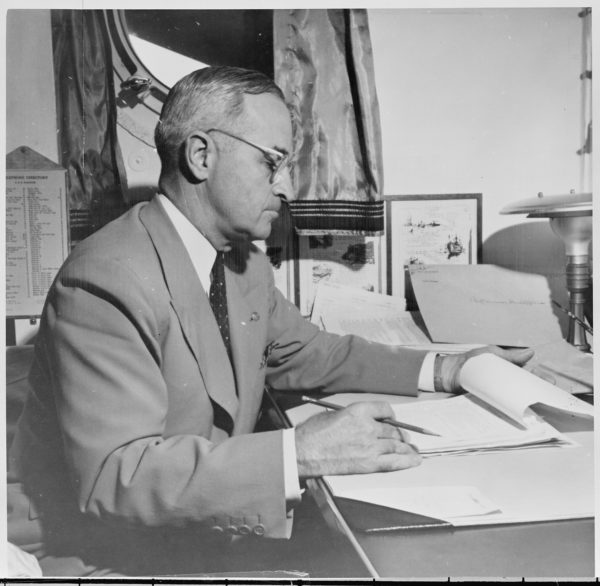

When Truman says he “made the first draft on the ship coming back,” he’s referring to his travel back from Europe aboard the USS Augusta. In fact, there is a photograph in the Truman Library that claims to be showing him writing this very draft:

“President Harry S. Truman at his desk aboard the U. S. S. Augusta, returning from the Potsdam Conference. He is preparing his “report to the nation.” August 6, 1945.” Source: Truman Library, 63-1453-47; scan from Wikimedia Commons

So, while many hands were no doubt involved, we can say with some reliability that Truman was very involved in the drafting process. How involved is a hard thing to say — but it gives us something to think about when looking at the specific language used, to question how much of it reflects the President’s own thoughts (something we cannot do with the original Hiroshima press release, which was written without Truman’s input).

I wrote the Truman Library awhile back and asked if they had any information about this statement, and they helpfully sent me a whole sheaf of papers taken from the papers of Samuel Rosenman, who was a Truman speechwriter and staffer. They included not only five different drafts of the radio address, but also many pieces of correspondence that helped contextualize it. For example, I was interested to find that the radio address as a means of communication was decided upon around July 20, 1945, as an alternative to giving Congress a full address, because Congress was going to be out of session when he got back.

The drafts are of course themselves the most interesting part. There are, as noted, five in the folder. They are all typed, and numbered but not dated. The fifth draft is not exactly the same as the version that Truman delivered, so we can deduce that there was at least one last round of changes, perhaps by Truman himself, perhaps not. There are, as we will see, some ways to date some of the drafts, based on the relationship between their content and some of the other letters in the folder.

The first draft, presumably related to the version first developed by Truman while on the USS Augusta (August 2–7). The atomic bomb was only mentioned very briefly, and in no detail:

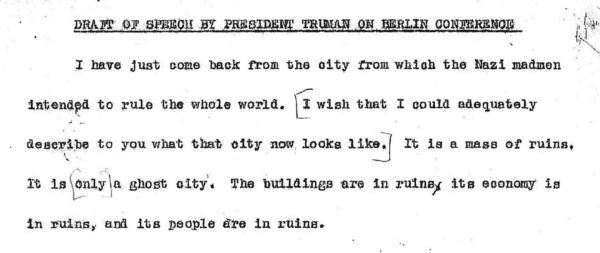

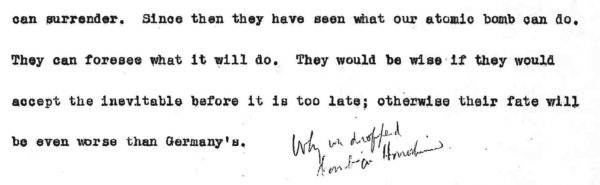

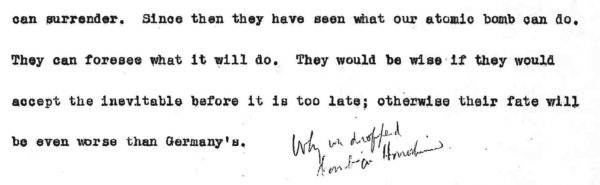

What we are doing to Japan now — even with the new atomic bomb — is only a small fraction of what would happen to the world in a third World War. […] We have laid down the general terms on which they can surrender. Since then they have seen what our atomic bomb can do. They can foresee what it will do. They would be wise if they would accept the inevitable before it is too late; otherwise their fate will be even worse than Germany’s.

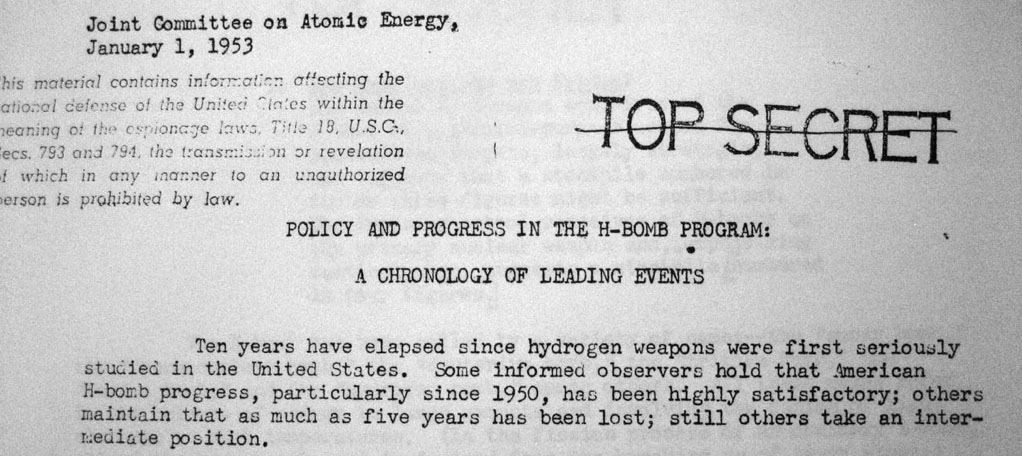

That’s it. I suspect this was written before Hiroshima, when Truman knew the bombing was scheduled to occur. What’s really interesting, though, is that underneath the final paragraph quoted above, someone has written in (by hand), the following: “Why we dropped bomb on Hiroshima.” So we can put some kind of boundary on when this draft was written: potentially before Hiroshima (as early as August 6th), but sometime soon after the bombing someone decided that there needed to be more on the atomic bomb in it.

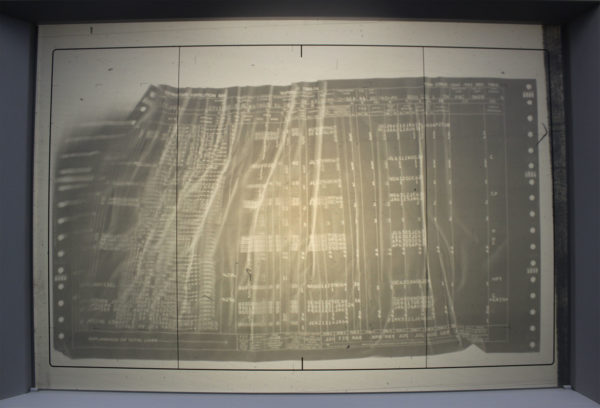

“The scrawl,” as I think of it.

How does this scrawl date it? Hiroshima was the preferred target for the first atomic bomb but it wasn’t until the mission was successful that anyone would have known it was the actual target. There were two backup targets as well (Kokura and Nagasaki); it is only on August 6th that it would have been talked about definitively as the bombing of Hiroshima. (Whose scrawl is it? I don’t know. Could it be Truman’s? Maybe. I am not a handwriting expert and it is not much to go by on itself.)

The second draft of the statement is much the same on the passages already quoted, but true to the penciled suggestion on the first draft, a new statement about the bombing of Hiroshima was added:

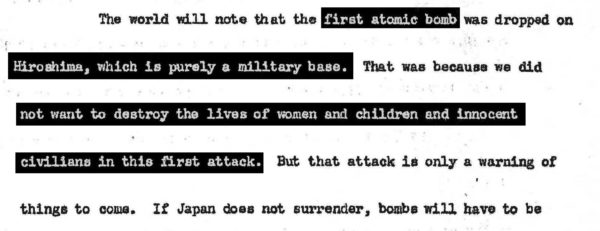

The world will note that the first atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima which is purely a military base. This was because we did not want to destroy the lives of women and children and innocent civilians in this first attack. But it is only a warning of things to come. If Japan does not surrender, bombs will have to be dropped on war industries and thousands of civilian lives will be lost. I urge the Japanese civilians to leave industrial cities and save themselves from destruction.

This is not so dissimilar to the language in the final statement but the differences are important. Let’s put them side by side:

- Draft #2: The world will note that the first atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima which is purely a military base.

- Final: The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base.

First, we have a confusion about how many bombs (singular or plural) were dropped. I don’t read much into that other than as an indicator of how quickly this was probably written.

Second, the original language is even more emphatic about the military status of Hiroshima: here it was purely a military base. “Purely” is a very strong modifier. Ask yourself under what conditions you would describe a city as being “purely a military base” — it’s hard to come up with any that are honest, if you understood the target to be a city. It is interesting, as well, that in the final version, Hiroshima is still listed as a military base — but the “purely” has vanished. Still a misleading statement (again, it was a city with a base in it), but it’s not as egregious as the original draft.

- Draft #2: This was because we did not want to destroy the lives of women and children and innocent civilians in this first attack.

- Final: That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.

This is another interesting and, I think, important juxtaposition. In the first one, it is claimed that “women and children and innocent civilians” were spared in the first attack. In the final version, this has been watered down quite a lot — only “civilians” (not even innocent!) are mentioned, the killing of which was only avoided “insofar as possible.”

Am I reading too much into language? I don’t think so. Because, strikingly, this language mirrors very closely another Truman passage, his Potsdam journal entry of July 25th, 1945, which he wrote just after making final decisions about the question of the bombing of Kyoto:

I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital or the new. He and I are in accord. The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and save lives. I’m sure they will not do that, but we will have given them the chance.

These two phrases are pretty distinct. Truman wants to avoid the killing of “women and children.” This is a phrase he uses again and again when talkig about the atomic bombs — first in talking about how his choices would avoid it, later to emphasize that this is what atomic bombs do. For example, in a speech he wrote in December 1945, Truman noted that the bomb would involve, “blotting out women and children and non-combatants.” In 1948, he told a group of advisors and generals that the atomic bomb was not a regular weapon of war, because, “it is used to wipe out women and children and unarmed people, and not for military uses.” I just point this out because Truman (like many people, including myself) has distinct turns of phrase that he deploys and redeploys repetitively, what at least one historian has called “Trumanisms.”

Even more striking is the repetition of the “purely military” phrase, which is much more extreme and particular to Truman. No one today would describe Hiroshima as “purely military,” and the scientists and military men who chose it as a target explicitly noted that it was not one. At the Target Committee Meeting at Los Alamos in May 1945, it was recommended that “pure military” targets not be considered: “It was agreed that for the initial use of the weapon any small and strictly military objective should be located in a much larger area subject to blast damage” — that is, a city, an urban area — “in order to avoid undue risks of the weapon being lost due to bad placing of the bomb.”

In my interpretation, the timeline so far looks something like this:

- Prior to the Hiroshima bombing (sometime between August 2 and sometime August 6), Truman drafts the radio address (little to no mention of atomic bomb)

- After the Hiroshima bombing (August 6), but before Truman knows the full extent of civilian casualties, Truman and others revise it to talk about Hiroshima

- Sometime before the final version is released (August 9), it is revised to indicate an awareness that Hiroshima was not “purely military” and that civilians were in fact killed in great numbers

On the second point — do we know that Truman himself modified the statement? We know he was (by his own account) involved in the revisions over the days. And the language is strikingly similar to his Potsdam journal. I suspect he was to some degree (even just in discussions) involved in forming that language, but the other possibility is that the Potsdam journal was used as “raw material” for writing that section (and it may have been why he kept the journal; Truman was not a diarist, and the Potsdam journal is unusual).

Do the rest of the drafts help us refine this timeline and the shifts in language? A bit. By the third draft, the singular/plural nature of the bombing of Hiroshima was resolved (“the first atomic bomb was dropped”), but it is still “purely a military base.” Most importantly, though, is that someone has added a line to it (on page 5) indicating that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan the day before, putting it at around August 8th or 9th in Washington (midnight in Tokyo is 10am the previous day in Washington, DC).

The fourth draft moves the paragraphs about the atomic bomb towards the end (from page 6-7 to page 17), which is an interesting change by itself. But it otherwise does not change them.

In the fifth draft, however, a change occurs. The language about Hiroshima as “purely” a military target still remains. But a new bit of text has been added:

Its production and use were not lightly undertaken by this Government. But we knew our enemies were on the search for it. We now know they were close to finding it. And we knew the disaster that would come to this nation, to all peaceful nations, to all civilization, if they found it first. […]

We won the race of discovery against the Germans.

Having found it we have used it. […] We have used it in order to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of Americans.

This is an interesting addition: it is the justification for having made it (the Nazis were going to make one) and having used it (we wanted to save lives). That it takes until the fifth draft — the last one in the archival file — for this to appear is fascinating. It is almost as if the speech drafters realized, all of the sudden, that they were going to have to account for its use, to make a case for the manufacture and use of the bomb that went further beyond their original one.

So when and where did this language enter into this text? Fortunately, there is another piece of documentation in the file that helps us. The Assistant Secretary of State (and former Librarian of Congress) Archibald MacLeish sent a letter to Rosenman dated August 8th, with “a paragraph which has some ideas you might wish to use about the atomic bomb.” It is not an exact match for the fifth draft’s language but it is so close on many points as to be the obvious source: “Its production and its use were not lightly undertaken by this Government. … Only the certainty that the terrible destructiveness of this weapon will shorten the agony of the war and will save American lives has persuaded us to use it against our enemies.”

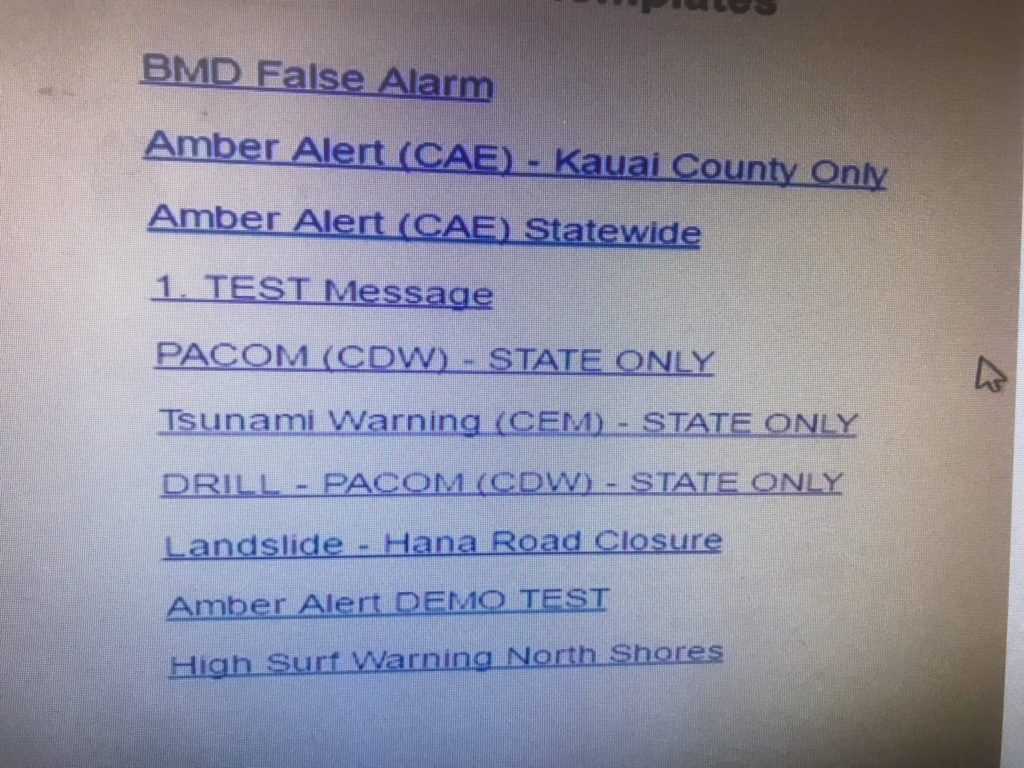

So that indicates clearly that the fifth draft was finished sometime after MacLeish sent his memo on August 8th. What happened on August 8th that would provoke MacLeish and others to think they needed to justify the creation and use of the atomic bomb? On the morning of August 8th, the first damage reports came back from Japan. These included the famous aerial photograph of Hiroshima, which was shown to Truman by Stimson that morning:

Damage map of Hiroshima, 8/8/1945. Source: National Archives and Records Administration / Fold3

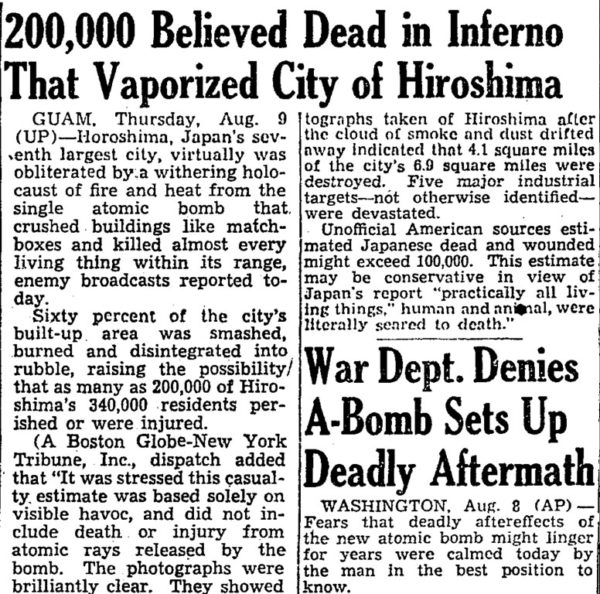

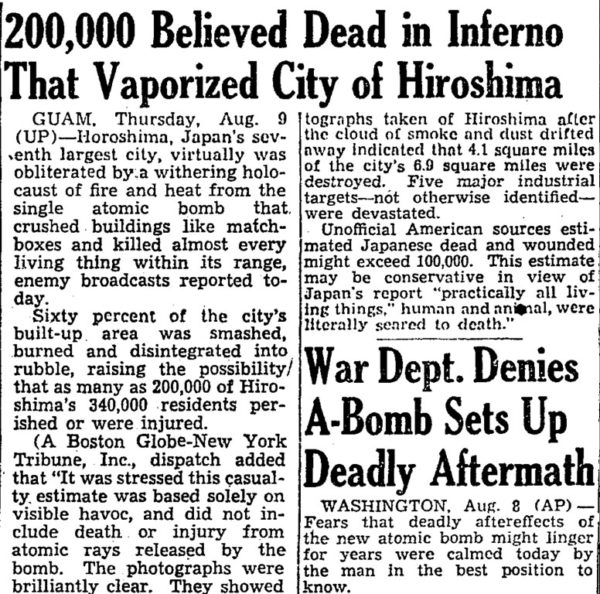

The Japanese also began to talk about the bomb damage for the first time in their newspapers, as the survey team sent to Hiroshima by the Japanese high command had finally sent its report back. (Someday I will write something here on this — it is its own interesting topic.) American newspapers on August 8 and 9th were reporting huge casualties: “Atom Bomb Destroyed 60% of Hiroshima; Pictures Show 4 Square Miles of City Gone” (New York Herald Tribune, 8 August); “200,000 Believed Dead in Inferno That Vaporized City of Hiroshima” (Boston Globe, 9 August). This latter estimate of the dead too high — it was created by just assuming 60% of the Hiroshima population were killed, as opposed to 60% of the area destroyed. But this is the sort of estimate that would persist until full surveys, by the Japanese and Americans, were done in the postwar.

If Truman believed that Hiroshima was “purely” military, there is no way he could have continued to believe that after August 8th. So sometime between that final draft in the Rosenman files (the fifth draft) and the final version delivered, the language about Hiroshima’s military status, and the sparing of civilians, got significantly watered down.

Is this conclusive? Not at all! This is highly interpretive, based on a smattering of sources. But history is the work of interpretation, and if one wants to understand the interior mental states of the long dead, one has to engage in this kind of triangulation of sources. I think it is plausible that Truman did not understand the nature of Hiroshima, and was rudely surprised by it on August 8th. That another atomic bomb would be used on another city on August 9th, I suspect, came as a surprise to him (he was not given any immediate prior warning).

Boston Globe (9 August 1945), page 2. Notice the typo in the first sentence: “Horoshima.” Just a typo, to be sure, but perhaps reflective as to how quickly this news was coming out, how unfamiliar these cities were to the American populace…

In my full paper, I discuss a bit what I think my conditions are for choosing one plausible interpretation over another. In this case, I think my interpretation solves some of these tricky questions about why Truman would persist in many ways to label Hiroshima as a “purely military” target. But more usefully, it also explains Truman’s sudden change in language after August 8th and 9th, in which he bluntly acknowledges that the atomic bomb was a killer of civilians. At his December 1945 speech mentioned earlier, he — in his own handwriting — refers to the atomic bomb as “the most terrible of all destructive forces for the wholesale slaughter of human beings.”

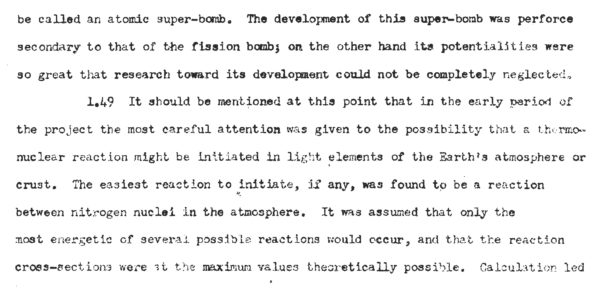

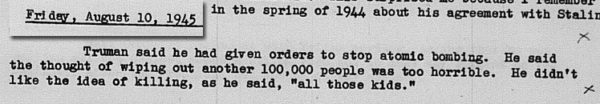

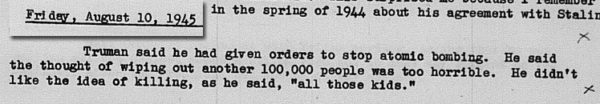

This is not the language of a man who is under a misapprehension about what the bombings did. On August 10th, he told his cabinet that “he had given orders to stop atomic bombing” because, as Henry Wallace recorded in his diary, “the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible. He didn’t like the idea of killing, as he said, ‘all those kids.’” This is a far cry from his initial reaction to hearing that the Hiroshima mission was successful: “This is the greatest thing in history!” I think something changed in him, and I think it was a horrible realization of his own misunderstanding of what this weapon would do.

Account of the cabinet meeting of 10 August 1945 in the diary of Henry A. Wallace.

We remember Truman primarily as the person who was president when the atomic bombs were first used. We should also remember him, as I have argued before, as the person who ordered that the atomic bombs stop being used. And the person who, over the course of his presidency, did the most to establish that atomic bombs were not weapons to be deployed lightly ever again. One might see this as irony, but in my interpretation, it is not: it the reaction of someone who realized he had been badly out of the loop once, and wore that on his conscience, and determined it would not happen again.